An interview with Kimberly Dougherty, PhD

By Sadie Bennison

Dr. Kimberly Dougherty is an associate professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy and has been here for five years studying rhythm generating circuitry in the spinal cord. Dr. Dougherty is an engaging young scientist who recently reached the exciting milestone of graduating her first doctoral student, Ngoc (Nesta) Ha (read Nesta Ha's story). In this conversation, we learn how Dr. Dougherty has generated her own rhythm from being a postdoc at the Karolinska Institute, where the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine is awarded, to being recruited to join the department where she has flourished as a mentor running her own laboratory.

Sadie Bennison: You had the experience of being at the Karolinska Institute for your postdoc. What was that like?

Kimberly Dougherty, PhD: Oh, I loved it over there! It was a good opportunity to get an international experience. I had planned to go for two years, for the traditional two to three-year postdoc, but I ended up staying for eight.

Oh wow, so was that by virtue of the lab that you were in? You loved the location?

Yeah, it was both. I really liked the lab, and I think even as a postdoc, it takes two years to really get things to the point where they are up and running. So then, projects were moving forward, the first paper was coming out at around three years. The main project took time but I knew it had the potential to be big. My supervisor had just gotten a big grant and he had said before that if he got the grant, he would be able to keep me for an additional five years.

So, tell me a little bit about this exciting project.

We were looking at a cell population in the spinal cord that had the potential to be rhythm generating, and it began as a collaboration between our lab and Tom Jessell's lab. They had created the mouse, and the postdoc from their lab came to Sweden often. Initially, she taught me how to do all of the genotyping and the crossing for the experiments, and she came to see some of the preliminary electrophysiology experiments that I took on. The electrophysiology experiments were difficult to get up and running but the results were exciting, and we were able to reconfirm them with other mouse lines that became available as we were completing the first set of experiments.

That sounds great! We have a lot of international postdocs from abroad studying here in the U.S., but I don't hear a lot of opinions from U.S. scientists who go abroad. I was wondering firstly, what was it like being an American postdoc abroad and secondly, I know that different countries view science differently, so I was wondering if you had any experiences like that.

The Karolinska Institute, especially the department that I was in, was highly international. So it was actually very easy to be a postdoc abroad there. Even when I was interviewing for other postdocs I interviewed for positions in the U.S. where I would've been one of the few American postdocs there. For your first question, it didn't really matter. It made it a very different environment where you have so many people that are international who just picked up and moved there so I was one of many with few connections when I first moved. In that case, it is easy to make friends and form your family away from your family pretty quickly.

Oh that's great to hear! And what about the science? Is there any way they think about science differently? Since it was such an international melting pot I imagine it might be more similar.

The structure of everything is different compared to here. I don't know how much of it is Sweden versus the U.S. versus other particular places. As far as viewing science, Northern Europe has very strong funding relative to most other places.

When you came back to the U.S., did you feel any differently about being back here?

Yes, I had reverse culture shock. It was rough and it took a while to overcome. Even more so than when moving abroad because then I expected everything to be different, and it was probably less different than I expected. Even with the language, everyone there speaks English because they're taking it from the time that they are in first or second grade. Also, none of the movies or video games or anything like that are dubbed, so they're exposed to it on a continuous basis. And then coming back you expect to know what you are coming into, and I think it's a combination of two things. Things in the U.S. have changed, and I'm sure I have changed as well based on the experience. I think it was just a case of expectations that were different.

That is very interesting, and it makes sense. When you came back, did you come right back to Drexel?

Yes.

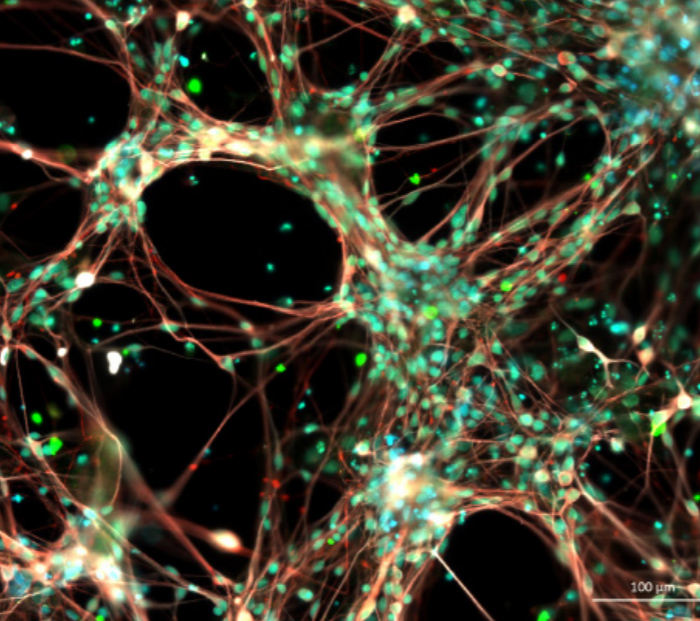

Neuronal Networking Night

Philip Yates

What brought you to Drexel?

I was really impressed with Drexel when I interviewed here. I applied here after talking to Ilya Rybak at SFN. He let me know that there was a position available. My former lab had collaborated with Ilya as well, so I knew him from that. I also knew, of course, Simon Giszter, and several of the other spinal cord researchers here before as well. So I came to interview, and I did not know what to expect. Firstly, I didn't realize that this was a separate campus. I expected that we would be down in University City initially, and I had looked at UPenn for undergrad and I did not like the environment. I came here thinking that I was coming for the science and we would see how it went with meeting the people, and I was really, really impressed.

What impressed you most?

The interaction of the people, and I think that is pretty common. How genuine everybody was here and how supportive everyone was. I got that impression from everyone I spoke with, within Drexel and outside. There was plenty of other faculty who were relatively new at the time as well. Also, I was impressed by how interested people were in my work and in collaborating. At other places where I interviewed, I would've been the only person or one of the two people working in spinal cord. At other places, the views were different and some asked why I wasn't looking at more of the interactions from the brain to the spinal cord, whereas here my interests in spinal circuitry were really embraced and it was seen as a natural fit with several other labs. The excitement from others about my work really helped me reach my decision. And, Itzhak Fischer and John Houle have very strong reputations for mentoring faculty as well, and for having their junior faculty succeed.

And do you feel like you've been provided with that mentorship?

Yes, absolutely.

What do you like most about being a research scientist and having your own lab?

About being a research scientist, I like that we can be curious and we can be driven by our curiosity. So if we are curious about something, we can actually think about ways to test it and go into the lab and actually carry that out. And about having my own lab, I like teaching the students and postdocs and other people in the lab. As a postdoc, I was focused more on a single project although I was coordinating many aspects of the project and had students and technicians working with me. Having many different projects running at the same time in my own lab is both one of the high points but it is also one of the toughest aspects to keep track of everything and to get used to the fact that you don't see exactly how every experiment run. It is both very rewarding to see results coming and that many things are working in parallel when you have good people who know what they are doing and are doing it well.

How many years have you been at Drexel?

Five years this week.

Congratulations! Have you noticed that Drexel has changed at all, or has there been any growth throughout the years?

I was kind of in the middle/tail end of the new faculty hires so I think the environment has changed in that way, but I didn't see much of what it was like before. I think the excitement and momentum in the spinal cord group, for example, was present when I arrived and that has maintained. I have seen more additions to the Systems group since Drs. Barson and Wang joined the department after me. I've seen that group build up and strengthen. Comradery and collaboration have always been high but I've become more involved in those groups and in specific collaborations.

Do you have a favorite moment at Drexel? You can have a few if it's hard to decide.

I've had a few, its hard. A lot of the firsts, like first MS and PhD students defending, the first student receiving a fellowship, the first paper as an independent were all big. If I think about back to the earlier times, I think after I was here for a year and a half I did a PPG seminar and for that, we were supposed to talk about the progress our lab has made in a year. Pulling up the pictures of the lab being unoccupied the previous March, and equipment kind of in the middle of the room to be away from the flood-ravaged area and then comparing to the year later showing that it was a fully functioning lab — that was super rewarding.

What do you like to do when you're not doing science?

I actually started taking piano lessons three or four years ago now. So I try to do that some. I also like urban hiking, city walking. I usually walk to clear my head. I also enjoy traveling both to new places and places where I have friends and family.

I noticed that you signed up to be a mentor for the Association for Women in Sciences (AWIS) this year. What made you want to sign up and be a mentor for this program?

It was Ankita. She came to me and I agreed because I think it's important to mentor others and to share your experiences. But also to learn from others. I also thought it would be a good opportunity to meet people who are in science but are not doing exactly what we do as well, to get some diversity of opinions.

Along the lines of being a mentor do you have a piece of advice that either helped you when you were an early career scientist or anything that you'd like other young early career scientists to know?

I have many little snippets from mentors, which I say in the lab that are funny and are related to specific moments. I'm sure he got this from a book, but my postdoc mentor used to always stress that to succeed in science, people have to both be smart and work hard. Doing one or the other is not good enough.