Correcting the Narrative: Harriet Cole’s Legacy

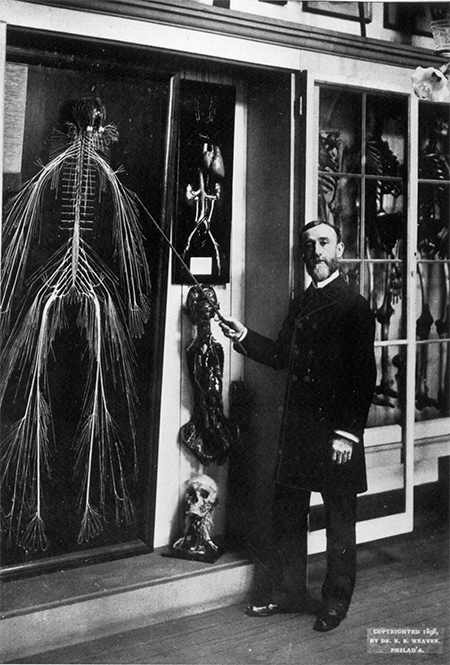

Rufus Weaver with the nervous system dissection in the College’s medical museum in 1898.

Generations of medical students at Drexel and its predecessor institutions have encountered the Complete Dissection of the Human Cerebrospinal Nervous System Known as “Harriet” created in 1888 by anatomist Rufus B. Weaver, MD. He was the first to complete such a dissection, and the specimen became an important neurology teaching tool that was lauded throughout the medical world over the next century.

The nervous system dissection’s existence was impactful then and remains so today. But just as impactful is the story of how the dissection came to exist and how wrong the long-told narrative might be. The history of the specimen and the woman named Harriet Cole sheds light on issues of medical ethics and informed consent, as well as the health inequities that were rampant in Rufus Weaver’s time and persist today.

The Story We’ve Told

The narrative that has long been relayed about the specimen is as follows: Harriet Cole was a custodial worker at Hahnemann Medical College while Weaver was an anatomist there. She was African American and between 35 and 40 years old, and she willed her body to Weaver for use in anatomical preparations, for the benefit of science. Some versions of the story paint Weaver and Cole as having a friendly relationship. Many iterations of this narrative exist in the print record, and most seem to simply restate the details of previous versions of the story.

Searching for Facts

In 2015, staff at the Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections began to question the reliability of the story they were sharing. As a result, Alaina McNaughton, the Legacy Center’s social media outreach educator at the time, was tasked with exploring the topic. This work was part of a larger effort to improve the representation of women of color in archives.

The project aimed to answer three questions: Did anyone named Harriet Cole exist at the time and place of this story? Did anyone by that name donate their body to Weaver in 1888? Did a Harriet Cole work for Weaver or Hahnemann in that timeframe? The answers to these questions were ambiguous. Records indicate the existence of a Harriet Cole in Philadelphia at roughly the right time, who died of tuberculosis in 1888 and whose burial location was listed as Hahnemann Medical College. Body donations were not well-documented during this time, so no definitive records of a donation exist. And Hahnemann’s staff records did not list employee names, just expenditures on wages.

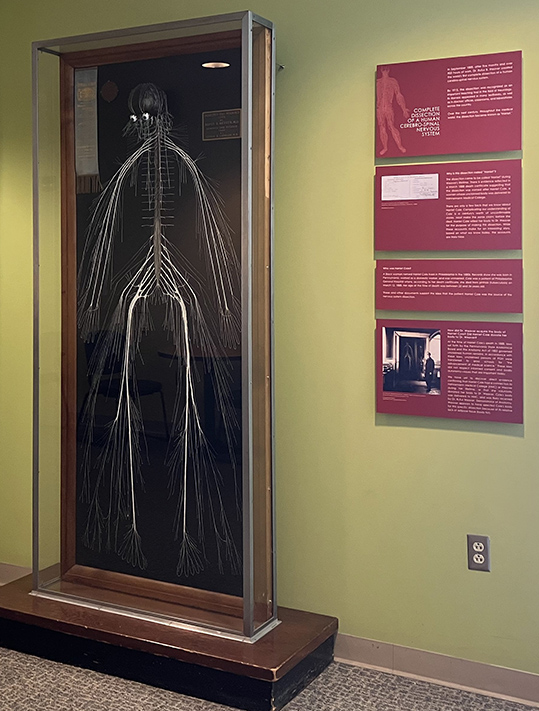

The current exhibit at Queen Lane, which includes updated text panels addressing the changed understanding of the dissection’s history.

To the question of whether the oft-told narrative of Harriet Cole is accurate, we can’t know is a straightforward answer. It is also a superficial one. While records are sparse, broad understanding of the culture at that time is plentiful. In a 2018 blog post1, McNaughton notes, “1888 was still an era when body donations were not documented as rigorously… It was also an era when most Americans disapproved of dissection and voluntary body donations were quite rare.” She goes on to say that in many states, bodies used for anatomy work were those of people who died in hospitals, asylums or prisons, making body donation a signifier of poverty. So, while it is possible that Harriet Cole chose to donate her body, either to help Weaver or to remove the burden of costly burial from her family, it is not especially likely.

Time for Change

The Legacy Center has continued its work to understand the story of Harriet Cole and the nervous system dissection, and correct the narrative publicly. These efforts have expanded to include the College of Medicine’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, the Department of Neurobiology & Anatomy, and the Office of Educational Affairs.

In 2021 and 2022, the Legacy Center updated the specimen’s exhibit labels to reflect the known facts and recontextualize the exhibit focusing on informed consent. In conjunction with these updates, the Legacy Center posted a “Historical Human Remains”2 section to their website. It outlines the problems with the existing Harriet Cole narrative, provides important context about the culture and laws of that time, and offers supporting documentation where available.

“The story of Harriet Cole allows us to examine how the ethics around body donation, consent, and bodily autonomy have changed over time, and to explore why gaps and erasures in history may exist.”

— An excerpt from the updated text panels that accompany the physical exhibit at Queen Lane

“As archivists, we’re responsible for being transparent about biases and gaps in the historical record and ensuring we provide as accurate a record as possible. This is a constantly evolving process. With the nervous system dissection, one way we’ve addressed these issues is by shifting from telling a mythical story about a medical marvel to a conversation about 19th century medical ethics and their impact on health care inequities today,” says Margaret Graham, director of the Legacy Center.

Students Leading the Way

As the Legacy Center worked to address the inadequate telling of the Harriet Cole story, Samiza Palmer and Willow Pastard, members of the MD program class of 2025, approached the team with concerns about the specimen and how it was being introduced to incoming students. They became active participants in discussions with College of Medicine leaders about the specimen, and they reviewed the updated language used in the specimen’s exhibit. In large part due to the students’ efforts, Legacy Center staff members Matt Herbison and Kieran McGhee ran orientation sessions addressing the nervous system dissection issues for the entire incoming medical class in August 2022.

Leon McCrea II, MD, MPH, senior associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion and director of the Drexel Pathway to Medical School (DPMS) program, lauds the students’ insights and initiative as central to this process. “Samiza and Willow are two amazing medical students who I have known since their time in our DPMS program,” says McCrea. “They are uniquely attuned to the lived experiences of disenfranchised communities and the importance of their contributions to the field of medicine. Their steadfast leadership was central to the process of modifying the content of our MD student orientation.” The students also wrote a blog post about their experiences.3

In the post, Palmer and Pastard note that their anatomy lab instructors began their first day in the lab with humanizing stories about whose bodies they would be dissecting, making it clear that respect for their cadavers’ “ongoing personhood” was essential.

The contrast they saw was stark: “Unlike the people we celebrate on that first day of anatomy lab, we cannot confirm that Ms. Cole willingly donated her body. We must thus acknowledge that her autonomy was potentially violated (as likely happened to many others) by laws that institutionalized medical discrimination in Philadelphia. This stands in contrast to current donation practices and the ethic of patient choice emphasized to Drexel students today.”

In exploring the importance of Drexel’s role in telling Harriet Cole’s story accurately, they add, “During our medical education, Drexel rightfully sheds light on egregious examples of medical discrimination and apartheid — HeLa cells, the Tuskegee syphilis study, etc. — but it is equally important to shine that light inward. The ‘Harriet’ exhibit exists within a canon of medical advancements that came at an ethical cost and presents an opportunity to educate students about the relationship between the marginalization of communities and medical advancement. It is imperative to discuss that relationship, because these histories exist on a continuum that informs the realities of medicine today.”

Looking Back and Ahead

Confronting our own biases is a critical step for growth and change for both individuals and institutions. Instead of perpetuating the narrative around Harriet Cole as a willing participant, we can now emphasize her absence from the record and use this to prompt important discussions about why she’s not there. “We are at a crucial junction in the field of medicine. As an educational institution, we embrace the collective responsibility to accurately depict medical advances and the sacrifices that have been made in the name of progress,” says McCrea. “We must continue this conversation and lean into the inherent imperfections of our discipline’s history.”

Back to Top