A World of Learning

International experiences help students develop cultural competency and a deeper understanding of health disparities.

In an increasingly connected world, physicians cannot practice medicine in a vacuum. That's why Drexel University College of Medicine promotes medical student participation in programs for education, research and service in underserved communities both in the United States and abroad.

"Medicine should not be taught or practiced in a silo," says Nielufar Varjavand, MD, director of the College's Office of Global Health Education. "We need to be aware of the endemic diseases and health conditions in other areas of the world so we can respond to those needs. When we talk about global medicine, we're talking about political, environmental, social and economic issues that all come to bear on health and health care."

Students at the College of Medicine have long undertaken volunteer missions during the summer after their first year in school. Varjavand's office opened in late 2015 in response to student requests and the College's desire to make those experiences safer and more structured. The office also guides fourth-year students who want to choose an international rotation as an elective.

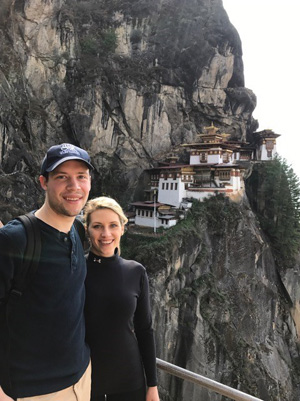

Drexel medical student Matthew Recker in Paro, Bhutan with wife on hike to Paro Taktsang (Tiger's Nest Monastary).

"When we started the office, we had three students who were doing an international rotation for their fourth year," Varjavand says. "Now we're up to 10." Participation by first-year students in summer programs has also grown, from 13 students to 19 this year, in addition to those who set up independent trips.

In fact, students are seeking out opportunities earlier and earlier. "I even have undergraduate students writing to me before they start medical school here," Varjavand says.

Students are encouraged to take part in established summer programs such as those offered by Child Family Health International or Unite for Sight. They are also welcome to find other programs to join or create their own. The possibilities are numerous, Varjavand says.

"We have a health and ethics class at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev with field work in Israel. We have students working in Ghana, Honduras and India, partnering with local sites in those countries. We are also developing a health education project in Cuba with Drexel's School of Public Health."

Fourth-year students also can join established programs or find their own opportunities for an elective rotation. "One student created a trauma surgery elective in Nigeria," Varjavand says. "Another worked on a Navajo reservation."

Typically, students fund their own trips. Students who participate in an approved program are eligible to apply for a competitive partial scholarship. The office is looking to provide more funded programs, like one it currently offers for maternal/child health in Uganda. Some students find financial support through Fulbright scholarships and other national programs.

As students travel and see health care from another perspective, they not only develop their empathy and their skills, Varjavand says, "they tell me that they're now dedicated to improving health systems in a new way. The experiences are often life-changing."

SURGERY IN BHUTAN

When he started medical school, Matt Recker knew he would get involved with global medicine, and he joined the Global Health Interest Group at the College. "The group has been a great way to spread awareness about international medicine to medical students, and we also give student scholarships of $1,000 to help students do this type of work," he says.

As a fourth-year student, Recker signed on to a Surgicorps International mission to Bhutan, led by Surgicorps' founder Jack Demos, MD, a plastic surgeon in Pittsburgh. "The medical team consisted of Dr. Demos and three other plastic surgeons as well as me and my wife, who is a nurse. When we first arrived in Paro, we screened about 150 patients a day for the first two days. I would record the interviews with patients and find out what they needed and discuss their options with them."

Patients who heard about the mission on radio and television often traveled three or four days to consult with the doctors, which in itself was eye-opening to Recker. "Health care there is nothing like it is here. To say that infrastructure is lacking is an understatement," he says.

Team members were at the hospital from 7 a.m. until 5 or 6 p.m. providing care. About 50 to 60 percent of the patients had cleft palates. The others needed facial reconstruction or skin grafts for burns. "We also gave out reading glasses and offered knee injections for those with pain," Recker says. "The patients are so grateful for our assistance — it makes you gain an appreciation for what people have to endure and how much health care means to them."

For Recker, who just began his neurosurgery residency at the University at Buffalo, the trip to Bhutan was only the beginning of what he hopes will be a career-long dedication to global medicine. "I have a passion for this type of work, and it's something I want to be involved with for the rest of my career," he says.

IMPROVING PUBLIC HEALTH IN ECUADOR

The faces of (l-r) Drexel medical students Lathia, Butchy and Golkowski were painted with traditional markings by Shuar boys.

In 2016, Margaret Butchy, Hiral Lathia and Anna Golkowski — then rising second-year students — joined a summer trip to Ecuador sponsored by Child Family Health International. For Butchy, her first impression of the country and its health care system was powerful: "The chaos of the early morning traffic stood in stark contrast to the serenity of the quiet rice paddies framed by misty, blue mountains. When we arrived at the clinic, a huge crowd of people stood chanting and pounding on the chain-link fence of the small building," she says.

Inequity and a lack of access to medical resources became a dominant theme of the trip. "Our experiences in Ecuador largely took place in public clinics where quality of care suffered from the lack of funding: doctors limited annual examinations to quick verbal interviews, clinical supplies were shared or simply unavailable, and health care professionals were overworked and underpaid," Butchy says.

The students' first assignment was to work with a vector-control brigade from the Ministry of Public Health. Going door to door, the students would inspect the homeowners' water tanks for mosquito larvae, distribute larvicide, and provide education. Lathia explains: "I would talk to the residents about the symptoms of dengue, zika, and chikungunya, and what to do if any members of the family exhibited those symptoms."

Drexel medical student Anya Golkowski takes a clinic patient's blood pressure.

The students also made home visits with obstetricians who travel through the community to register pregnancies and conduct checkups. Then the trio had the opportunity to shadow doctors in the rural area of Puyo. Here, the differences in care and access were stark, Golkowski says. "For example, one clinic, only 40 minutes away from a small city, was supplied with almost all medications needed to treat the population. However, a clinic about an hour and a half away from the same city did not even have multivitamins for children."

The culmination of the trip was a week spent with the Shuar tribe in the Amazon studying traditional medicine. During the nearly six-hour hike to the site, both Lathia and Golkowski suffered injuries, and on arrival, they experienced the benefits of traditional treatment firsthand. The chief manipulated Lathia's shoulder and Golkowski's arm and then wrapped the injured area in a medicinal plant that had been burned or smoked, lessening the pain significantly. "While I was skeptical at first, the effects of the plants were extraordinary," Lathia says.

MATERNAL MEDICINE IN MOROCCO

Drexel medical student Anya Venezia in Morocco with Love Volunteers.

In seeking a global health experience, first-year student Anya Venezia wanted to go to an Islamic country specifically to look at women's health care and how it might be different from here. She served a six-week internship at Matérnité des Orangers in Rabat, Morocco, a public hospital that provides only obstetrics and gynecology. "I found the program through an international organization called Love Volunteers, which connected me to the Rabat-based Moroccan Center for Arabic Studies, and set me up with my internship," Venezia says.

Each day, Venezia attended a staff meeting held to review cases and then joined doctors on service, observing cesarean sections, changing bandages and helping monitor contractions in the birthing suite — a rewarding opportunity for her because she was directly involved in care. "No visitors were allowed in the birthing suites, so I would often be the only person to stay with a woman through her whole labor," she says.

At the same time, the program gave Venezia a broader perspective about health care around the world. "This internship in Morocco was the first time I ever saw a really under-resourced medical environment," she says. "There were not enough doctors to serve the patient population and not enough materials to go around."

Venezia came away with a better understanding of how she might improve health outcomes, and even a more defined vision for her career. "This experience helped me understand the roles I could play going forward in addition to practicing medicine. Looking at how I could contribute to affecting health outcomes, I realized that on an individual level I'm passionate about observing cultural differences and doing statistical research, but I also saw how important larger organizations are for implementing sustainable improvements," she says. "I think a global health experience is indispensable for anyone planning on a career in medicine."

LESSONS FROM HONDURAS

Drexel medical student Genevieve Fasano in Honduras.

"Her weatherworn skin, an indication of age and exposure to the brutal Honduran sun, was not what I noticed first. My patient's ankles were grotesquely swollen. She had the characteristic edema of heart failure, and when I took her blood pressure, it all made sense: the numbers were as high as readings I had seen only in textbooks. Listening intently to her story, I examined her dirt-caked feet and was moved by her sweetness and overwhelming gratitude.

"After spending a year absorbed in the basic sciences that define the preclinical years, I found myself faced with the decision of how to spend my one "free" summer between the first two years of medical school. Should I find a new research project? Apply for an internship? As I thought about the options, I realized I sought something deeper, a project that would allow me to delve into one of my passions: global health. That realization took me 2,000 miles into the mountains of Honduras, where I encountered this elderly patient and so many others like her.

"I served in a dual medical–public health brigade [through Global Medical Brigades] made up of physicians, dentists, students and local volunteers. The first leg of our mission was to provide health care to the extremely remote community of El Rosario. Our mobile medical clinic was set in a simple cement building with four rooms and a latrine. It was actually a primary school. Many of the patients had never come into contact with a medical professional, and on the first day of our clinic, the long line wrapped around the building.

"I began interviewing patients to gather medical histories and take vital signs. As the morning progressed, I saw the pride with which each mother presented her children to me. Dressed in their best, the children were excited to be getting measured, and the mothers were grateful to be able to provide them with this basic form of medical care. It was remarkable to witness such an outpouring of appreciation.

"As the week progressed, I noticed a pattern in the conditions that needed treatment: fungal infections, upper respiratory tract irritation, diarrhea, parasitic infections and rotted teeth, which stemmed from poor living conditions and a lack of sanitation. Without clean water, mothers can't protect their children from parasites. Without a toothbrush and toothpaste, oral hygiene is unattainable.

"When clinic concluded, we had seen more than 700 patients in five days. As we departed, tearful community members told us that we would always be welcome, and that our work was a blessing.

"It was time to move on to Buena Vista, another remote community, where we put our efforts into improving the living conditions of several families. The pathogenesis of many of the diseases we treated in clinic was clear when we arrived.

"Over the course of several days, we provided health care by replacing a dirt floor with a cement floor for the family to sleep on, building a private latrine and sanitation station, and retrofitting a stove to route the smoke outside, rather than trap it in the dwelling. Every family member living in the home, from the 6-year-old girl to the elderly grandmother, was eager to assist us.

"While in Honduras, a phrase kept rolling through my mind. "A little for a lot, and a lot for a little." Regardless of how small I perceived our efforts to be, the impact on those we encountered seemed enormous. When it was time to leave Honduras, I realized that my time there would never leave me."

— Genevieve Fasano, Class of 2018

If you are interested in making a contribution to students' global health experiences, please contact Andrea Pesce at adp77@drexel.edu or 215.432.7934.

Back to Top