Rewriting the Book on Alzheimer's Disease

With his latest research, Garth Ehrlich, PhD, could potentially change Alzheimer's treatment —and even the way we talk about this disease — for future generations.

By Elisa Ludwig

"We're testing the hypothesis that Alzheimer's disease — which perhaps should be called Fischer's disease — is triggered at least in some cases by infection," says Ehrlich, a professor in the Departments of Microbiology & Immunology and Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

Currently, the widely accepted idea is that Alzheimer's disease arises when neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques form in the brain — resulting in brain cell death and fewer nerve cells and connections, which eventually impairs cognitive function — but the root cause of these plaques and tangles is not definitive.

"There's no bigger health problem in first world countries," Ehrlich says. "In the U.S., we currently spend about a quarter trillion dollars a year on direct health care costs and another quarter trillion in lost wages to family caregivers. It is anticipated that the direct costs will go to $1 trillion by 2050."

Since last year, Ehrlich's research has been funded by James Truchard, PhD, co-founder and chairman of the board of National Instruments, as part of what is called the Oskar Fischer Project.

Oskar Fischer

1876-1942

Oskar Fischer was a Jewish academic, psychiatrist and neuropathologist working in Prague in the first half of the 20th century. In 1907, he published a paper describing 12 cases of senile dementia with neuritic plaques — essentially determining the clinicopathological definition of what became known as Alzheimer's disease. During the Holocaust, Fischer was arrested and taken to a political prison, where he died, and in the ensuing years his work fell into obscurity. Meanwhile, Alois Alzheimer wrote about the presence of plaques and tangles in one case of dementia the same year that Fischer's paper came out. In 1910, a colleague named the disease for Alzheimer in an important book, and Fischer's contributions went unrecognized.

Enter Jim Truchard. An electrical engineer who turned his company into a multinational enterprise, Truchard has committed funds to Alzheimer's research projects while aiming to resurrect Fischer's important legacy.

"I chose Drexel's Institute for Molecular Medicine & Infectious Disease for the Oskar Fischer Project because of the center's advanced genome sequencing capability and Garth Ehrlich's unique experience with biofilms and bacteria that can evade the immune system," Truchard says. "Dr. Ehrlich's expertise is critical for establishing a definitive answer to the question of whether spirochetes or other bacteria reside in the brains of Alzheimer's patients."

A NEW PATH OF DISCOVERY

The philanthropic support has allowed Ehrlich and Drexel to purchase a higher-throughput DNA sequencing device, which will be used for the research. The team will screen blinded samples of patient brain tissues for bacteria and analyze the specimens for evidence of infection.

"Eventually we will do the same for fungal and parasitic infection, but for our first assay we will be looking at bacteria," Ehrlich says.

For the past several months, Ehrlich has been working on operationalizing and validating the latest-generation equipment, and he is now looking at the first set of specimens. "We suspect that all the brains will have some level of bacteria because of the sensitivity of the assay and because there are no real sterile sites in the body, contrary to what we used to believe," he says.

The new instrument allows the team to look at about 160 specimens in a single run. "That is a huge increase in our capacity. The rate-limiting step is preparing all of the samples, but we anticipate that we can get the bacterial assays done by the end of the summer and hopefully the fungal and parasitic samples by the end of the year," Ehrlich says.

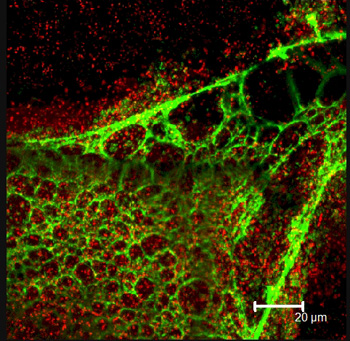

Confocal microscope image of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. The red dots are individual cells; the green is the matrix they produce, stained with lectin.

Ehrlich will be looking to see if there are more or different types of bacteria in the Alzheimer's patients. One of the reasons Ehrlich believes that infection could be the likely culprit is because of what the brain looks like in syphilis patients.

"When that disease kicks into the final stages, it causes a dementia that's very similar to Alzheimer's disease. I was shown this by Dr. Judith Miklossy [director of the International Alzheimer Research Center at the Prevention Alzheimer International Foundation in Switzerland] about four and a half years ago, and it really opened my eyes to the possibility that infections could be the trigger here."

The concept was not a stretch for Ehrlich, who has been working for nearly three decades on characterizing medical conditions that were thought to be nonbacterial processes as bacterial. In the early 1990s, he began by looking at chronic middle-ear disease, which was considered nonbacterial because children with persistent middle ear problems did not respond even when treated with multiple courses of antibiotics. Ehrlich and his colleague discovered live, metabolically active bacteria in the ear that could not be cultured. The bacteria had actually formed a biofilm whose cellular physiology was impervious to antibiotics.

"We tend to think of bacteria as a single-celled organism, but when it becomes a biofilm, it's going through a process of change that is more profound than a caterpillar turning into a butterfly or moth — it becomes a multi-celled organism."

This paradigm — of infection that hides behind a hard-to-culture biofilm — applies to many other diseases and conditions that researchers are studying, including sinusitis, cystic fibrosis, urinary tract infections, periodontitis and others. Biofilms are also associated with infections from implanted devices, which are notoriously unresponsive to antibiotics and can only be stopped when the implanted device is removed.

Ehrlich hopes that his research will conclusively show the link between infections and the inflammation that leads to beta-amyloid plaques. "About 25 years ago, Dr. Sue Griffin at University of Arkansas came up with the idea that Alzheimer's disease was an inflammatory process, and she wasn't taken seriously at first. She demonstrated it with her research, and now it's part of the dogma that this is an inflammatory condition. She believes that our hypothesis is a reasonable idea, and she is a collaborator on our research."

While other researchers are looking at similar links, some in the Alzheimer's community have expressed skepticism about Ehrlich's hypothesis.

"People have dismissed this idea out of hand, which I find very troublesome. We might be wrong, but let's rigorously test this hypothesis before we decide. We're not saying that all Alzheimer's disease is caused by an infection, but some subset of it could be," he says.

If a bacterial trigger can be identified, then researchers could develop a testing method for bacteria in the central nervous system so that patients would know their likelihood of getting the disease before the onset of symptoms. There may also eventually be a way to stop the progression, he says, that is similar to what is used in Lyme disease patients — a high-dose intravenous antibiotic.

Ehrlich's mother died of dementia a couple of years ago, so he understands what it is to live with this extremely common disease that affects some 5.4 million Americans. "We're not sure if what my mother had was classical Alzheimer's because she might have had vascular or mixed dementia and she had several mini strokes. It's not why I got involved in this research topic, but I have come to see how hard it is for family members taking care of dementia patients. My sister had to quit work for the last three years of my mother's life to take care of her. Meanwhile, the NIH and big pharma companies have spent over $60 billion on research, and it's done nothing to change these outcomes."

Of course, along with meaningful research results comes an opportunity to bring awareness about an important figure in the history of science, something that Ehrlich, himself an amateur historian of science, values deeply. "Most people have never heard of Oskar Fischer. We won't ever replace the Alzheimer name, but we should establish Fischer as a co-equal in the development of this medical paradigm. What Truchard has done for this field of research is pretty incredible."

Back to Top