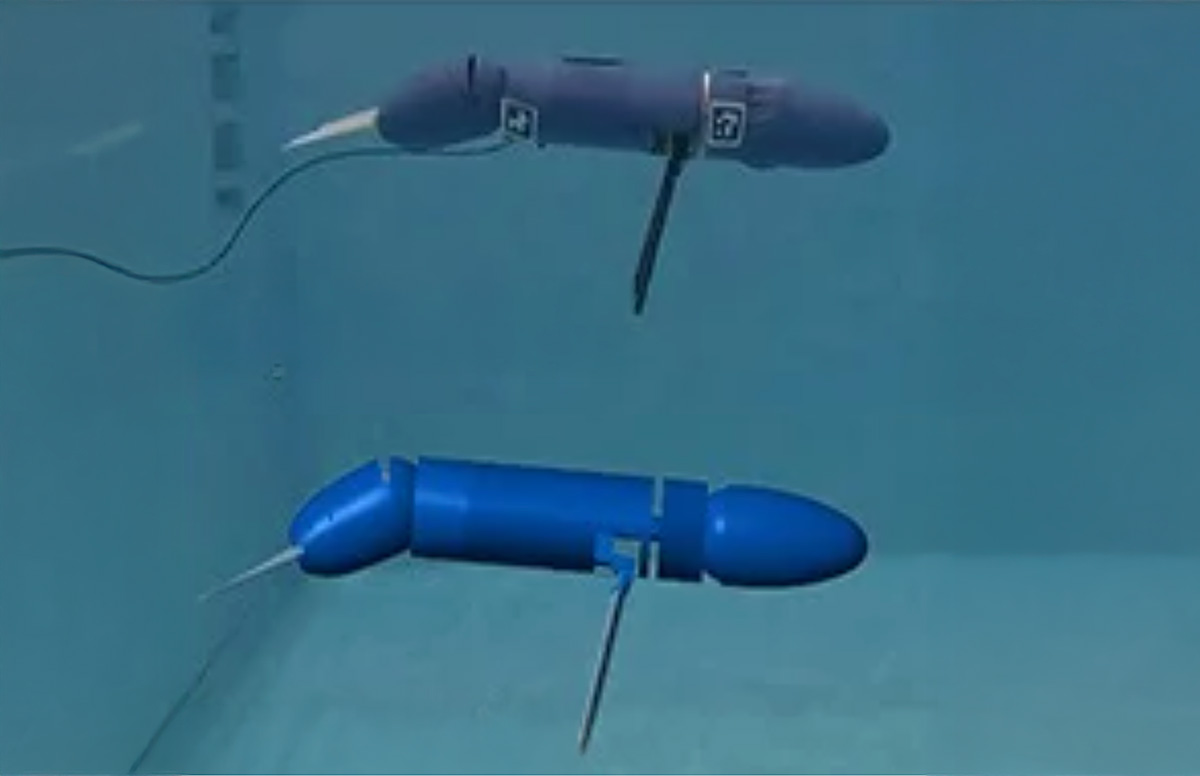

Top: SEAMOUR, the robotic sea lion. Bottom: Its digital twin.

Top: SEAMOUR, the robotic sea lion. Bottom: Its digital twin.

A Drexel Engineering team has developed a highly accurate numerical model that predicts how their bio-robotic sea lion swims and maneuvers underwater, providing a powerful tool for optimizing design, testing new control strategies, and accelerating future robot development.

Directed by Harry G. Kwatny, PhD, professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics, with lead author Shraman Kadapa, PhD, along with Nicholas Marcouiller, Anthony C. Drago, PhD, and James L. Tangorra, PhD, the study appears in Biomimetics and addresses a fundamental challenge in underwater robotics: accurately modeling a non-propeller based multi-body systems that swim freely in three dimensions.

The numerical model that was developed by the team is a high-fidelity computational representation for SEAMOUR (Stroke Experimentation and Maneuver Optimizing Underwater Robot), a bio-robotic platform inspired by California sea lions. Unlike traditional underwater vehicles that rely on propellers, SEAMOUR uses its flippers and articulated body segments to swim and maneuver, making its non-linear dynamics considerably more complex to predict.

"Numerical modeling is a powerful tool for studying the biomechanics of multi-body underwater robots, but existing approaches often rely on simplifying the model, which limits their applicability for complex bio-inspired systems," Kwatny explained. "What makes this work unique is that we derived the equations of motion in closed form for a freely swimming vehicle with non-uniform body segments—something that hasn't been done before for this type of system."

The team used a Lagrangian based approach called the Euler-Poincaré formulation to derive the robot's equations of motion, which capture the articulation of all seven major body segments – the main body, head, pelvis, and four flippers. This method expresses linear and angular velocities in the local body fixed frame for each control surface, making it easier to estimate the hydrodynamic forces produced by each moving body segment.

To accurately estimate these hydrodynamic forces, the researchers combined computational fluid dynamics simulations with analytical strip theory, then refined the key parameters using a genetic algorithm. This optimization step proved crucial for reducing the sim-to-real gap.

"By turning simple physics-based formulas into a full simulator, we show how theoretical science can directly support real world applications," Kadapa said. "Engineers can now use these tools to gain deeper insight into the dynamics of the system, which is essential as we work towards autonomous operation of the robot in complex underwater settings."

The model achieved over 99% accuracy in predicting forward motion and approximately 90% accuracy in predicting rotational rates and orientation during maneuvers. These results were validated through multiple swimming and maneuvering trials, each involving different combinations of body-segment actuation.

The validation experiments took place in a pool where the robot executed different swimming strokes and pitch and yaw-based maneuvers, while external cameras tracked its position and an onboard sensor recorded its orientation. The model was able to predict the robot's translation and orientation with strong agreement to the experimental results.

This research builds on the lab's ongoing work developing bio-inspired underwater vehicles. The numerical framework now provides a validated tool for analyzing performance, testing control strategies, and optimizing swimming gaits without requiring extensive physical trials. Moreover, the numerical model that derived the equations of motion in closed form also enable advanced model-based control strategies, bringing the system one step closer to autonomy.

"With a validated numerical model, we have a baseline understanding of how the robot would behave across different operating conditions," Tangorra noted. "With this foundation, we can improve its design and control strategies much faster than relying on physical testing alone."

The team's framework establishes a foundation that can extend to other articulated underwater robots, offering a systematic approach to modeling complex, multi-segmented swimming systems that learn and adapt biological locomotion.

Read the full paper at https://www.mdpi.com/2313-7673/10/11/772