Nearly a quarter of Division I college athletes reported depressive symptoms while enrolled at a liberal arts university on the East Coast, says a new study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (February 2016, Volume 50, Issue 3). Women were almost two times more likely to experience symptoms than their male peers.

Researchers at Drexel University College of Medicine and Kean University collected data over three consecutive years from 465 undergraduate athletes at an NCAA Division I private university.

The multiyear sample is one of the largest to date used to look at depression in college athletes.

While past research has tended to focus only on specific sports or genders, this study examined whether the prevalence of symptoms varied between genders and across nine different sports: baseball/softball, basketball, cheerleading, crew, field hockey, lacrosse, track and field, soccer and tennis.

During their annual sports medicine physicals, the athletes completed anonymous surveys that asked questions about their mood, appetite, attention, relationships and sleep habits. Based on the responses, the student athletes were assessed for depression using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

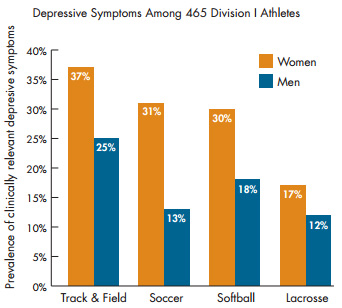

The researchers found that nearly 24 percent of the 465 athletes reported a "clinically relevant" level of depressive symptoms, and 6 percent reported moderate to severe symptoms. Across all sports, female athletes had a significantly higher prevalence rate for depressive symptoms than men, 28 percent compared to 18 percent.

When analyzed by gender and sport, some differences were even more pronounced: Female track and field athletes had the highest prevalence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms — 37 percent, or more than one out of three — making them two times more likely than others in the cohort to have symptoms. At 12 percent, male lacrosse players had the lowest prevalence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms.

Until now, there has been a scarcity of medical research measuring rates of depression in college athletes, says Eugene Hong, MD, associate dean for primary care and community health at the College of Medicine, and the study's principal investigator.

"There is a perception among some people that athletes are immune to or at a decreased risk for depression. Our experience treating college athletes led us to believe that was not true, but there were very few studies to support either argument," Hong says. "This study shows that the rates of depression among athletes are probably comparable to rates in the general college population. And it highlights the need for increased mental health screening for athletes as part of standard sports medicine care."

While student-athletes may be active and surrounded by a strong support system, they may also experience a number of stressors unique to the athletic experience, including high-pressure expectations and injuries, says study co-author Andrew Wolanin, director of the Department of Advanced Studies in Psychology at Kean.

"Student-athletes face pressure, and there is a lot of opportunity for failure, which can be a key component of depression," he says.

The study's authors note that a number of factors could have contributed to differences in depressive symptoms by sport. For instance, since the researchers surveyed athletes from a single institution, the results could have been unique to particular teams.

Another consideration is that "different personality types may engage in different sports, and that these choices are related to divergent forms of pathology," they write. "Differences in social support factors between more individualized sports and team sports may also contribute to discrepancies in depression rates."

Given the study results, Hong says that healthcare professionals who treat student-athletes for injury should also increase their attention to their patients' mental well-being. While a growing number of college students are seeking help at mental health services, athletes may be less likely to use these resources due to time constraints and social stigma.

Since the study identifies groups that may be at higher risk for depression, the findings could also help clinicians to target high-risk athletes for intervention, Hong says.