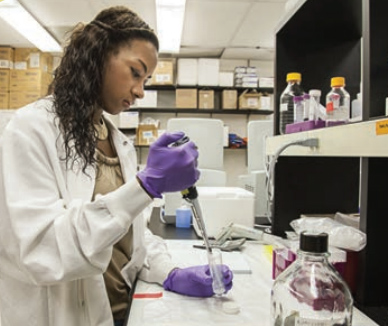

Unlocking the Secrets of HIV: Lauren Bailey, PhD Candidate

From the time she was in elementary school, Lauren Bailey wanted to be a doctor. Influenced by her mother, who was a nurse, she fully intended to apply to medical school.

All that changed during her senior year at St. Joseph's University when she started conducting research in the chemistry lab of Jean M. Smolen, PhD, director of the university's environmental science program. Bailey was drawn to Smolen's environmental studies, and her passion for chemistry was ignited.

"I switched my goal from being a doctor to full immersion in basic research as a result of my work with Dr. Smolen," Bailey explains. "We were studying variables, such as pesticides, that affect the reductive dissolution of iron oxides, which are commonly found in soil. We were looking at how pollution or pesticide use in everyday processes can react with iron oxides, thereby posing a human health risk. This research inspired me to pursue my PhD in biochemistry."

Research by PhD candidate Lauren Bailey is helping to advance our understanding of the structure of HIV and how an inhibitor may cause the inactivation of the virus.

Bailey chose biochemistry because she wanted to add a more in-depth understanding of cellular systems to her strong background in chemistry.

Before pursuing her PhD, she worked for a year in a generic pharmaceutical company. "I really loved that experience," she says, adding that she might like to become part of a pharmaceutical research and development team after receiving her PhD. "I would also consider working for a branch of the government like the Environmental Protection Agency. Researching environmental pollutants has always been an interest for me as well."

Bailey chose to pursue her PhD at Drexel because "the professors wanted to know what techniques I was interested in learning, not just what I already knew. They made it clear that whatever I wanted to know, someone here would help me. That's what really appealed to me. As a multidisciplinary university, Drexel has really benefited my thesis research because, even if my lab doesn't specialize in a particular area, there are so many other professors throughout Drexel that I'm able to utilize. That has been a great experience for me."

Working in the lab of Irwin Chaiken, PhD, for her thesis project, Bailey has been investigating why an HIV inhibitor identified by a previous student causes the inactivation of HIV.

"Our group works on molecular mechanisms and protein interactions in biology and disease," explains Chaiken. "Our current research is focused on interaction mechanisms of the HIV-1 envelope surface and the attempt to find inhibitors of the surface protein complex — known as Env — that targets cells for infection."

"During Lauren's thesis work, we learned that when a particular Env-binding inhibitor [a peptide triazole thiol] is mixed with the virus, it causes the virus surface membrane to develop holes, so the contents of the virus leak out and the virus itself becomes non-infectious," Chaiken continues. "Lauren's project was to try to understand how the thiol component is able to cause virus lysis. She has submitted a very important paper on this topic. The first major part of her thesis was to use a synthetic approach to determine the structural relationship between that thiol, the Env protein binding site in the peptide, and the binding site for the peptide in the Env. She followed this up with computational modeling in collaboration with another student and more recently a postdoctoral fellow to find out where that thiol group could be interacting with the Env protein. Her project has advanced unique hypotheses about how the thiol actually can cause the inactivation of HIV after peptide triazole docking onto the virus," he says.

Bailey is co-president of the Graduate Student Association and served as student ambassador on the research day committee.

"The second part of her project is to try to deepen our understanding of the way the thiol works," Chaiken continues. "We now know that it's important, that it has a specific spatial relationship to groups in the envelope protein. In this next phase, we're trying to understand mechanistically how the thiol functions."

Bailey hopes that another therapeutic for HIV could be developed as a result of her research. "Even if our group doesn't develop a therapeutic, just knowing more about the structure of HIV and getting more information about inactivation mechanisms can help toward downthe-line development of therapeutics. It's exciting to be advancing science with our work," she says.

Bailey says she has grown as a scientist under Chaiken's mentorship. "One of the great things about Dr. Chaiken is that he isn't always looming over your shoulder. If you have questions, he's willing to answer them. But then he gives you your space and independence. He really appreciates seeing PhD students and post-docs take initiative. So he won't necessarily tell you what your next steps are, he wants you to tell him what you think your next steps should be. That's been a great experience for me because it has allowed me to think in depth about what's actually going on in my research," notes Bailey, who expects to complete her PhD degree in the fall of 2015.

Chaiken says Bailey is "one of the most motivated, goal-oriented students I've had. It defines her. She's had great perseverance and focus throughout her doctoral training period and has made important contributions to our research. The biological implications of the project she's working on are extremely strong. Her work is helping to show a correlation between the deactivation [of the virus] we see in the absence of cells and the infection we see in the presence of cells. This correlation could provide important insights into how the Env protein functions in cell infection as well as suggest implications for the treatment of HIV."

Back to Top