The Mother of Philippine Obstetrics: Honoria Acosta-Sison

October 29, 2021

In recognition of Filipino American History Month, we focus on Honoria Acosta-Sison, a Filipina who studied to become a physician at one of Drexel’s predecessor schools, Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, and then returned to the Philippines to practice. Her story speaks to the impact and effect of being born and living under colonial rule and how cultural assimilation can echo for decades. An avid researcher, teacher and physician, Honoria Acosta-Sison had a long and varied career caring for and advocating for Filipina women.

Born Into Unrest

Often cited as the first Filipina physician, surgeon and obstetrician, Honoria Acosta-Sison was born in Calasiao, Pangasinan, in December of 1888. She was born into a time of upheaval and resistance, and the bulk of her childhood took place during two historical crises for her people. The Philippine Revolution began in 1896 against Spain and continued into the early 1900s against the United States after the islands were ceded to the U.S. as a result of the conclusion of the Spanish-American War. After it became apparent that the U.S. would not recognize the First Philippine Republic, the Philippine–American War then began.1,2

Under Spanish rule, education for Filipina women was limited. And still, under the United States' rule, no medical school located in the Philippines awarded a full medical degree.3 However, one of the many ways that the U.S. attempted to institute “benevolent assimilation” was via educational opportunities.4 In 1904, the second round of the pensionados program (a scholarship program for Filipinos to attend school in the United States and in turn, foster beliefs in the supremacy of U.S. systems, language and culture) commenced.5 Hundreds of young Filipinos took the exam. Ten were selected to receive scholarships. Only two of this group were women: Honoria Acosta-Sison and Olivia Salamanca.

First Filipina Doctor

Perhaps prompted by the loss of a cousin to labor complications, in addition to the general suffering she observed resulting from a lack of more medicalized maternity support, Acosta-Sison was moved to study medicine.

After being selected as a pensionada, Acosta-Sison prepared for medical school at the Drexel Institute and Brown Preparatory School in Philadelphia before entering the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP). While a member of the class of 1909 at WMCP, she won an anatomy prize on competitive examination offered to the freshmen class, an honor that she would proudly list on her curriculum vitae for decades.6

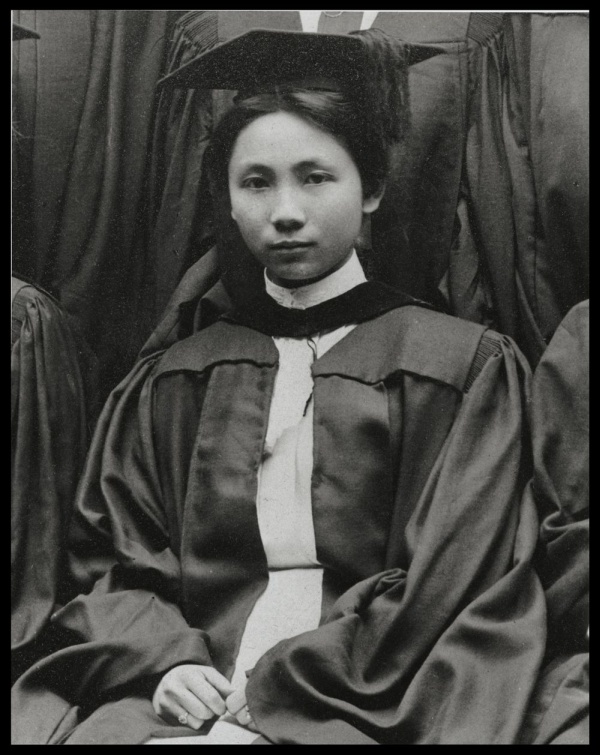

Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison in her Class of 1909 photo.

Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison in her Class of 1909 photo.

Driven as Acosta-Sison was to master Western medical practices, she was also eager to embrace “American values.” While at WMCP, Acosta-Sison became the editor-in-chief of the Philippine Review, founded to defend "the interest and aspirations of the Filipino people in America." In 1909, she proudly graduated from medical college, becoming "the first woman of her nationality to become a physician."7 Acosta-Sison specialized in obstetrics for another year as a resident in the Maternity Hospital of WMCP before realizing her goal of helping her community in the Philippines.

Return to the Philippines

Acosta-Sison returned to the Philippines in 1910 and began her practice in obstetrics at St. Paul’s Hospital. While there she married fellow pensionado recipient Dr. Antonio Sison, and they would go on to have three children together: Antonio (Tony, b. 1919), Honoria (Nori. b. 1921), and Pastora (Patsy, b. 1923).8

Two years into her practice, Acosta-Sison became an instructor at the College of Medicine and Surgery at the Philippine General Hospital in Manila. Constructed by the United States colonial government, the hospital mirrored American medical and clinical practices of the day and also functioned as a teaching hospital.

It is perhaps because of this and her nostalgia for her time at WMCP that Acosta-Sison embraced America's colonial influence as a positive change to her homeland. When World War I broke out and 100 women physicians petitioned President Wilson to serve their country as medics, Acosta-Sison desired to join their numbers and “pay tribute to the national cause.”9 Her attitude toward Filipino subjugation would evolve as life went on and the political landscape of her country continued to change.

A letter from Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison to Clara Marshall.

A letter from Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison to Clara Marshall.

Throughout Acosta-Sison’s career, her research agenda and her medical practice worked in tandem. In her early career, her research focused on the correlation between the pelvic measurements of Filipinas and the hand size of their newborns. She almost exclusively used the information gathered from her patients to conduct this research, a practice that would be considered unethical and illegal by modern standards. A mentee of hers, Gloria T. Aragon, described Acosta-Sison’s access to research facilities as “nonexistent” and the clinical workload as “very heavy.”10 Acosta-Sison would go on to introduce the low cesarean section to her practice and the country after observing one being performed in Europe.

In 1927, Acosta-Sison visited locations in south Asia, including India and Indonesia. This experience troubled her. She asked, “Are some races condemned perpetually to be under the yoke of some other races, as we ourselves have been for the last 400 years with no relief in sight?”11

In addition to seeing patients, Acosta-Sison was an associate professor of obstetrics and an inventor of obstetrical instruments. A prolific researcher and writer, Acosta-Sison wrote and published nearly 200 papers and articles relating to medicine and frequently focused on obstetrics, particularly chorioepithelioma and choriocarcinoma. In 1936, Acosta-Sison published a book entitled Obstetrics for Nurses. During her career, Acosta-Sison presented her research at conferences, congresses and meetings over 50 times. While she continued to be a figurehead in the research community, she and her colleagues organized the Philippine College of Surgeons in 1939.12

Independence

World War II brought with it a new imperial power in the form of the Japanese occupation. During this time, Acosta-Sison’s work was never published, and she continued her work at the U.P. College of Medicine and the Philippine General Hospital. Allied troops defeated Japan in 1945. On July 4, 1946, the Philippines was officially recognized by the United States as an independent nation through the Treaty of Manila between the governments of the United States and the Philippines.13

After the liberation of Manila, Acosta-Sison went on to serve as the chief of obstetrics and gynecology of the Provisional Philippine General Hospital until she was recalled as the Head of Obstetrics at U.P. Acosta-Sison was a founding member and the first president of the Philippine Obstetrical and Gynecological Society. While serving in these positions, Acosta-Sison championed state-funded pre- and postnatal care clinics, paid maternity leave and maternity hospitals.

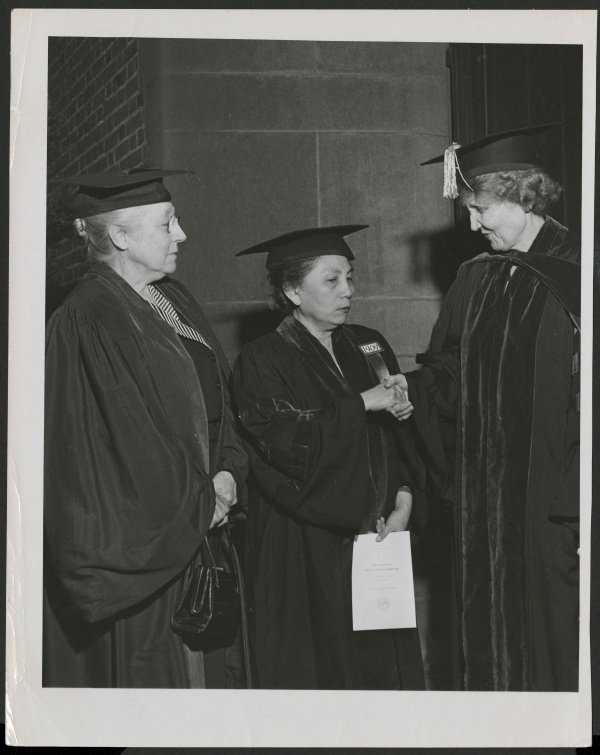

Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison receives her honorary degree from WMCP.

Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison receives her honorary degree from WMCP.

In her retirement, Acosta-Sison continued her work with the medical community; she served on the board of directors of the Philippine Obstetrical and Gynecological Society, was appointed to the Committee on National Mole and Chorioepithelioma Registry of the Philippines, and became chairman of the Society’s Maternal Mortality Review.

Acosta-Sison’s career was an impressive one, complicated by the cultural implications of being a physician raised and taught in colonized society. The list of her accomplishments, awards, certificates and other honors is extensive.

Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison, a woman who lived through three imperial regimes and undoubtedly played a major part in the medicalization of childbirth in the Philippines, died in Manila in January of 1970 of lobar pneumonia.

Additional Resources

For further reading about colonialism and the history of the occupation of the Philippines, please check out these sources and/or contact a librarian:

CuUnjieng Aboitiz, Nicole. Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887–1912. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines: a Pictorial History / Ricardo T. Jose, Lydia Yu-Jose. 1st ed. Metro Manila: Ayala Foundation, 1997.

Kawashima, Midori. “The Records of the Former Japanese Army Concerning the Japanese Occupation of the Philippines.” Journal of Southeast Asian studies (Singapore) 27, no. 1 (1996): 124–131.

The National Archives of the Philippines (NAP)

Punzalan, Ricardo L. “Archives of the New Possession: Spanish Colonial Records and the American Creation of a ‘national’ Archives for the Philippines.” Archival Science 6, no. 3 (2006): 381–392.

Root, Maria P. P. Filipino Americans : Transformation and Identity Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 1997.

For further reading about Dr. Honoria Acosta-Sison please check out these sources and/or contact the Legacy Center:

Honoria Acosta-Sison, M.D. papers, 2002.004, The Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections, Philadelphia, United States.

Philippines, Manila. “Biographies of Early Scientists in the Philippines.” (2004).

Pripas-Kapit, Sarah Ross. “Educating Women Physicians of the World: International Students of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1883-1911”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2015.

Windsor, Laura Lynn. Women in Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Oxford: ABC-CLIO, 2002.

References

-

Linn, Brian McAllister. The U.S. Army and Counterinsurgency in the Philippine War, 1899-1902 Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989; 75–76.

- For more information about the Philippine-American War and its impact on the Philippines please see sources listed below.

- “Pensionado Act of 1903.” The Greenwood Dictionary of Education, 2011.

- Gilbert, Helen, and Chris Tiffin, eds. Burden or Benefit?: Imperial Benevolence and Its Legacies. Indiana University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1zxxz79.

- Panganiban, Leah L.; Bonus, Rick (2014). "Filipino Americans (Education)". In Danico, Mary Yu (ed.). Asian American Society: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4833-6560-2.

- Drexel College of Medicine, Legacy Center, Deceased Alumni Files (DAF), Honoria Acosta-Sison 1909.

- Acosta-Sison DAF.

- Butler Margaret F., Brydon M. Evelyn, Miller Albert G., and Hartley Harriet L. b. The Esculapian, Vol. II, No. 6, 1911.

- Acosta-Sison Honoria. Honoria Acosta-Sison to Clara Marshall, 1917. https://drexel.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01DRXU_INST/1aqopv8/alma991014993665204721

- Gloria T. Aragon, “Postgraduate Training and Specialization,” in The Road I Travelled: A Memoir (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2005), pp. 7-8.

- Acosta, Sison, “A Retrospect: A Conference Read Before the Academy of Arts and Letters, University of the Philippines, January 10 1929,” in Glimpses of the East and West, 81.

- Acosta Sison DAF.

- Philippines. Treaty of General Relations and Protocol with the Republic of the Philippines : Message from the President of the United States Transmitting the Treaty of General Relations and Protocol Between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines, Signed at Manila on July 4, 1946. District of Columbia, 1946.