Drexel medical students learn how to understand and communicate with people with complex disabilities from the best possible teachers — people living with disabilities themselves. Their instructors are residents of Inglis House, a specialty nursing care facility that provides long-term residential care for adults with physical disabilities, including multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury and stroke.

Every year, first-year medical students spend an afternoon at Inglis learning about its people and programs and then meeting individual residents in their rooms. This relationship started in 1998 and has continued ever since as part of the freshman Physician & Patient course.

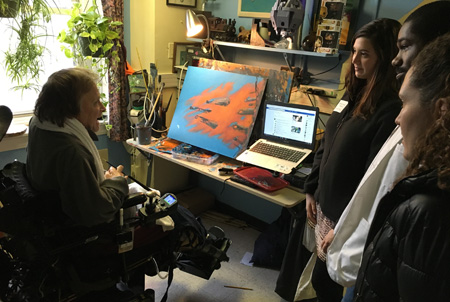

Robert Woltanski was an art major in high school but didn't take it seriously. He started painting again when he came to Inglis.

The goal of the sessions is threefold: to enhance the students' understanding of the issues involved in caring for patients with severe disabilities, to enhance their ability to communicate with those patients and, perhaps most important, to help them better understand the personal attitudes and emotional reactions they may have toward patients and how these may inhibit or enhance patient care.

"It's all about cultivating empathy," says course director Dennis Novack, MD, professor of medicine and associate dean for medical education. "It takes time. The students have to overcome their fears and first impressions, and get to the people inside. It gives them an understanding of how people with disabilities can build lives despite major limitations. Students are often inspired by the residents' wisdom, optimism and hope."

As an institution, Inglis, which also provides community-based services and accessible housing, is an ideal setting to counter stereotypes about nursing care facilities and their residents — a "least restrictive environment" where residents can be engaged not only in the Inglis community and its therapeutic and enrichment programs, but also in the larger community and the pursuit of personal interests and hobbies.

The Drexel students began the afternoon in an introductory session conducted by Novack, Inglis staff and some of the residents. On their tables with literature about Inglis was As the Wheels Turn, a collection of short pieces by Diane, one of the residents, who describes the environment as "a soap opera on wheels." Diane has severe cerebral palsy and communicates with great difficulty, but her mind is sharp and her wit is keen.

One of her articles attested to the great importance of the computer lab to residents. She, for example, prepares for trips to the mall or restaurants by previewing stores or menus. As the students would learn, many of the people living at Inglis are engaged in activities beyond the confines of the building or an uninformed imagination.

A resident named Ty explained that he used to be in a rock band. He was a chef, and he also showed his artwork in a gallery. "All these things came to an end when I contracted MS," he said. "Inglis House represents for me another chance, another opportunity to explore my interests and hone my skills. I still paint every day, even though I'm not as good as I used to be. It's just change, and how we respond to it is what defines us."

Inglis's focus is person-centered care — not only providing for people's needs but helping them to achieve their goals, whether they want to go back to school or get up early and eat breakfast with their friends. Adaptive technology is used to enhance activity. "If you can move any part of your body, we can get you on the Internet," said a staff member.

The facilitators dealt frankly with the issue of pity — a common emotional response in working with someone who has a severe disability. "Pity is the simplest reaction to a more complex situation," said one resident, "and a way for people to distance themselves from us."

"It's not so much about pity," said Gary Bramnick, director of marketing and public relations at Inglis. "It's a matter of mindset. It took me a while to understand that to engage with someone you had to let them engage back — take the time to let them respond."

This prompted Novack to recall how he got to know Diane: "I met her the way Gary described — rushing by," he said. "Then one day I noticed that she was holding a loose-leaf binder. She very slowly asked if I wanted to read it and I said yes. It was some of her writing."

After the students went in twos and threes to interview residents in their rooms, they came back to share their experiences and perceptions. What was the hardest thing for them? How did it make them feel? What emotional and social resources have helped the residents cope?

The other side of that coin, perhaps, is that patients with severe chronic disabilities often have questions that the physician cannot answer. Novack and the students discussed ways to deal successfully with the patient's and family's reactions to the limits of physician knowledge.

Ty thanked the students for coming, expressing confidence in their future: "You are going to have the opportunity in your life to boost people up and give them hope again," he said.

His confidence was borne out a few weeks ago when a graduating senior told Novack how important the Inglis House visit was to him. "I came out of that session saying to myself, you better start being compassionate — you never know what people have been through."