Medicine & the Arts: Multi-Talented Physicians

Artists and scientists, who are sometimes both, have more in common than many people would guess. The products of their work may be poles apart, but the creative processes are similar. Consider the shared vocabulary: observation, discovery, discipline, empathy. Alma Dea Morani, physician and artist, wrote that the study of art helps physicians understand the human condition. Another source suggests that the actual practice of art makes them more resilient. For the highly accomplished musicians and visual artists who tell their stories here, the practice of art is central to their being.

During a distinguished career as an oncologist, Wilma Bulkin Siegel also worked with some of the first patients diagnosed with AIDS and established one of the first AIDS hospices. Her awardwinning art has been exhibited across the country. She is president of the Foundation for the History of Women in Medicine.

When I was 7 years old, I decided to be either an artist or a physician, and in reality I'm both. And it is a passion. Art has taught me so much about the human being, and of course medicine has taught me so much about the human being. I've been passionate about bringing art into medicine because I believe it's a way of teaching medical students why they're doing what they're doing.

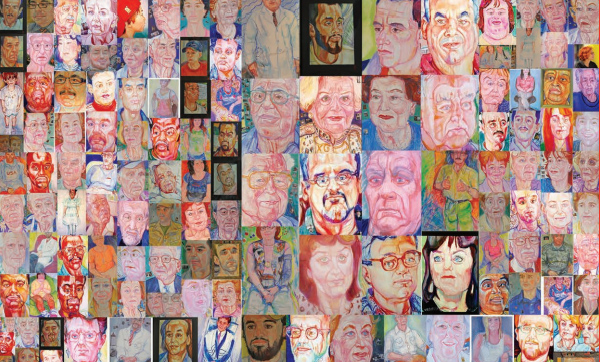

A collage of Dr. Siegel's watercolor portraits (most are 30-by-40 inches) includes examples from several series: Holocaust Survivors, Second-Generation Holocaust Survivors, Female Doctors and Returning Veterans. Website: wilmabulkinsiegel.com

All throughout my career I did art. I used art as stress management for myself when I was dealing with oncology. I went to the New School in New York City to do sculpture. Because the cancer was tearing down bodies and so was chemotherapy, in some ways doing sculpture and building up bodies helped me emotionally.

In the process of transition from practice to retirement, I went to the National Academy of Design, and they told me I was already an artist. I've always done painting — in high school, I did murals for the dances, and I did cartoons for the newspaper in high school and college. I was also pretty much an expert in theater makeup. As I developed my art, I became a portraitist. Initially I was doing paintings of subjects who were dealing with the illnesses that I took care of, such as AIDS and breast cancer, and I grew to understand that some of that was a healing process for them. I wrote a narrative to go along with the painting, and so it was very similar to what I was doing in medicine, in that I was doing the history, and then as I was drawing and painting on the paper or canvas, it was almost like doing a physical examination; and when I brought it back to the studio to develop the painting, it was the diagnosis and the treatment, as I did with the patient. Many times when I would spend time and validate that personin what they were dealing with, it was healing for that individual. I found as I went into more social issues — such as Holocaust survivors and liberators — that it's still the same process, that I'm validating who they are, making that individual be as important as everybody else, telling their story and painting who I see in a psychological viewpoint.

I am now adding video to some of the portraiture, so it's a contemporary approach to portraiture. I do a video so the actual person can be seen alongside my interpretation in the portrait, and what they have to say [can be heard] alongside my interpretation in the narrative.

My most recent series was returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. I do an individual portrait from life — I always do the portrait from life — and then I tell their story as I've received it. They often edit the story; I won't expose it to the public unless they agree. I will give them their portraits when I am finished showing the series.

I think there is creativity in science and there is science in art. In medical school so often it is so left-brain logical training that we need to have that other, intuitive training. [Involving medical students with art] is really to stimulate the right brain. Art helped me be a better physician, I think. It helped me better see the whole, and I believe it stimulated my creativity in medicine: I went into oncology when it wasn't a field. I went into hospice when it wasn't a field. And I went into AIDS when it wasn't a field. All that is because I was seeing the whole and the needs of the whole.

My mentor, Alma Dea Morani, was a woman who promoted art in medicine. The Foundation for the History of Women in Medicine created a "Renaissance Woman" award, which we named the Alma Dea Morani Award, and she was the first to receive it. Before she died, she said to me, "Wilma, carry on the vision." I continue to carry on whatever I can.

Back to Top

The late Alma Dea Morani (1907-2001), clinical professor of surgery, was known as the first female plastic surgeon in the United States. The daughter of a sculptor who wanted her to follow in his footsteps, she was a skilled artist who thought the study of art had a vital place in medical education.

Dr. Morani honed her inborn talent with private art lessons in the 1950s. She created this bust of her father, Salvatore Morani, around 1962. Of Italian birth, he studied sculpture in Naples and Rome before immigrating to the United States.

The closeness between art and science has long been recognized, although the relationship is difficult to define. The end goal of both art and science aims to improve the education, comfort, and enjoyment of people. We accept that both art and science require study, thought, reasoning, talent, and discipline, and both subjects are best learned through years of study and largely through visual impact. …

Few of us recognize that art, when really understood, is the province of every human being, for it is simply "doing things well." It makes for self-expression and finding gain in the work itself. … There is ample proof that a desire for some creative activity is present in all humans and that it gives satisfaction to the creator. We refer to the cave drawings of prehistoric man as proof of man's need to express his emotions. 1

Art has been given a number of definitions. My accepted one is that art is a means of communication. … I feel art is not a luxury as many in the world do. Art is a necessity in life because everyone has a fundamental need for self-improvement, selfexpression. Even a child of a few years old — give him a pencil and he'll start scribbling something. …

The ability to express oneself with paint or clay or sculpture becomes art. Music is an art. A lot of doctors have musical talent. We even have a doctor's symphony orchestra in Philadelphia. We have an art club for physicians. 2

When Morani retired from surgery in 1972, she sharpened her focus on art in medicine, publishing and lecturing on the subject. In 1985, she gave MCP her art collection: [The Morani Art Gallery was my] gift to the Medical College of Pennsylvania because I was grateful to them for my good medical education. … We started by having six lectures on art and medicine by professional art teachers. I gave one. Then I donated my collection of art artifacts. … It's the only medical school in the country that [does this]. 2

Notes:

1. Excerpts from Morani, Ama Dea, MD. "Art in Medical Education: Especially Plastic Surgery" in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (Springer, January 1, 1992)

2. Excerpts from Roslyn Coskery Souser, MD, FACS. "Tribute to Alma Dea Morani, M.D., FACS, Sculptor, Plastic Surgeon, Teacher in the Year of the Woman, 1993: A Biographical Interview" in Worldplast: World Journal of Plastic Surgery (Vol. 1, No. 1., 1995).

Back to Top

Anu began to study music at her mother's behest, but grew to love it. As officers of DUCOM Classical, she, Canning and Lefchak organized the winter concert and performed in it.

The violin was the first instrument I tried. I started playing when I was 6. There are no musicians in the family, but my mother wanted me to have the opportunity to learn, and it is because of her that I stuck with the instrument at first. Then I started to teach myself piano as I made connections between the instruments. I can play piano — not very well — it's just something I like to fiddle with in my free time.

Once I started appreciating music, it became something I turned to when I was stressed or sad or happy or feeling pretty much any emotion!

I did consider pursuing violin professionally. When I was in high school, I was the concert master for the Chester County Youth Orchestra, and I loved it. I used to play for hospice patients, and that also helped me realize how helpful simply spending a day with patients could be. In college I was also, on and off, concert master of the Drexel University Orchestra. However, I loved sciences and medicine more, and so I chose to pursue a career in medicine. I do like playing in my free time, and hope to be able to play as we get further into medical school.

I like to play most styles of music — from Bach to Stravinsky to Coldplay. I can't really pick a genre. My favorite part of the violin is its ability to transfer multitudes of emotions and styles, by simple manipulations of the bow.

Back to Top

He loves to play classical music, but Brian enjoys nearly every genre. He struggled with the violin before finding his inner musician.

Out of the blue in fourth grade, I told my parents that I wanted to take up piano. Naturally, they were skeptical, but it wasn't long until my piano teacher told them I was going to need more than a little electric keyboard, and the rest is history.

I don't think the idea of music as a career has ever left me entirely. But I figured rather early on that I couldn't commit the time necessary to make a career out of classical music. Then when I started contemporary music, around 10th grade in high school — dabbling in songwriting and other instruments like drums and vocals, and eventually live performances and studio sessions — I saw firsthand how devoted one must be to the craft. I felt the uncertainty of the business was too much for me. But the best part about music is that it isn't a black and white game. I still play, perform publicly, and write music all the time — something I can do now and during my career as a physician — and that in itself is the best blessing I could ask for.

I wish I was able to play classical music more often, but generally these days I play whatever the next music project entails. When I'm not [preparing for something], I often tell people to name a pop song on the radio and I'll pretty much have it figured out within a minute or so (whether that speaks to my skill as a pianist or the lack of originality in today's pop music is open to interpretation). I really like playing drums and doing piano/vocal sorts of ballads as well. But I can easily find myself enjoying anything from Rachmaninov to jazz standards to hip-hop.

Back to Top

Elizabeth started piano lessons at age 5; well before that, she was plunking out notes on her own. She went to Penn State as a music major but was drawn to science.

I began trumpet lessons in elementary school, and switched to French horn in high school. I continued studying piano and horn and performed in almost every high school music ensemble. I also played horn with the Harrisburg Youth Symphony Orchestra.

My intention was to become an elementary school music teacher, set up a private studio to teach at home, and learn to play the organ, for church. But during my freshman year of college, I found I also loved math and science. I switched my major to nutritional sciences and minored in music. Throughout college, I continued to perform.

Right now, my favorite thing to do on the piano is sight read from my church hymnal; it keeps me grounded in my faith. I also like playing the Chopin waltzes. I would love to play in a horn or chamber ensemble.

Music and medicine require many of the same human characteristics. First, both require impeccable listening skills. Musicians need to be listening to the rhythm, rate, dynamics, pitch, and tone quality of themselves and of the other people in their ensemble in order to make beautiful music together. Similarly, physicians need to be listening to their patients' concerns and physical signs (heart and lung sounds with rhythm, rate, dynamics, pitch, and tone quality). Physicians also need to be listening to themselves in order to match the patient's feelings with appropriate empathy and self-expression.

Above all, I feel that much of both music and medicine is about reading between the lines. The late classical and baroque composers often did not mark how the music should be played. Likewise, many times a physician must notice the importance of what the patient is not saying. In either case, to do our best, it is our job to learn as much as we can.

Back to Top

Ben plans to go into family medicine. He studied epidemiology and biostatistics for his master's in public health. He serves on the board of directors for Prevention Point Philadelphia, an organization that serves Philadelphia's homeless and injection drug using communities.

Ben Cocchiaro sings, plays, arranges and composes. Have a listen at his website: thewh.bandcamp.com.

I started playing guitar in earnest when I was about 12. At the time I was listening to a lot of punk music — visceral, angry stuff played by do-it-yourselfers that fit my reaction to a world whose suffering and injustice I was only beginning to understand. The sentiment stuck with me as my tastes turned toward folk music, and I soon found in artists like Phil Ochs the same power and advocacy that had originally drawn me to louder groups like Dillinger Four.

When I first saw fingerstyle guitarist and Chet Atkins acolyte Tommy Emmanuel at the 2003 Philadelphia Folk Festival, the guitar was reinvented for me as an instrument capable of profound expression — what the late ethnomusicologist Bob Brozman called "the intimate relationship between feeling and muscle action."

Playing music has always been a cathartic experience for me. I play almost every day. I'll do maybe three to four gigs a year. This past year I had the distinct honor of playing the Philadelphia Folk Festival, where I shared the bill with Tommy Emmanuel.

In addition to my original ragtime compositions, I also arrange shape note tunes for banjo, guitar, and voice. Using a four-shape system of musical notation, patented in Philadelphia in 1798 and preserved as a living tradition of community singing throughout the United States, shape note music is choral singing that takes place with singers facing each other rather than an audience. On fourth Thursdays, I make the trek from my home in Kensington to the A-Space [an anarchist community center in West Philadelphia], and we'll take turns leading songs from either The Sacred Harp, first published in 1844, or The Shenandoah Harmony, published by some friends of mine in 2013.

The music is powerful, and while the poetry can be rather macabre, I find it particularly relevant to the practice of medicine. My first day in anatomy lab, I couldn't drive John Leland's "Evening Shade" from my mind: "We lay our garments by, / Upon our beds to rest: / So death will soon disrobe us all, / Of what we here possess." Singing this music with a couple dozen of my friends helps to give new meaning to Dr. E.L. Trudeau's edict "to cure sometimes, to relieve often and to comfort always."

Since starting medical school, I've been involved with the House of Grace Catholic Worker Clinic. They help support the Kay Lasante clinic outside Port-au-Prince, Haiti and have been doing this since before the earthquake. All proceeds from my music go directly there.

Back to Top

Dr. Keyser began life with a song in his heart, and throughout the years he has been able to join his passion for musical theater with his passion for medicine. At Hahnemann he was part of the medical school choir; as a practicing physician, he sang wherever he went.

When I was 15, I was certain I was going to become the biggest star in the history of Broadway. I wheedled my way into singing and dancing choruses whenever I could. I even did some television commercials. The production company liked the fact that I had no Philadelphia accent even though I grew up there. That was because my parents were both totally deaf. I spent my childhood enunciating very clearly so my parents could read my lips. It is ironic that I grew up in a house with no music whatsoever.

I received a scholarship to Temple University, but I attended rarely because I devoted my time to trying to make it in show business. When I finished college, I had no idea what I wanted to do except perform. I applied to medical school under pressure from my parents.

I found that I was as deeply in love with medicine as I had been with show business. I became an obstetrician and served as co-chair of the department at one of the largest hospitals on Long Island. I adored being in medicine, but I always had music in the back of my mind.

In the late ’70s, I began writing about health care; then other topics. My first book about music, Geniuses of the American Musical Theatre: The Composers and Lyricists, was published in 2009, and I’m working on a sequel about the performers of that era.

I’ve been performing on cruise ships for about 10 years, singing and lecturing about the theatre people I’ve written about. Since retiring from medicine three years ago, I do it about three months every year. So my life has gone full circle. It gives me a huge amount of pleasure.

While I was in practice, I also became interested in painting. Now my paintings hang all over our house. My father was very talented that way. Without any training, he became an artist and one of the foremost gilders in the United States. I have a picture of my father on top of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, gilding by hand the sculptures at the very top of the museum. My father never knew anything about music because he was deaf, but everyone who worked with him said that he always hummed while he was painting. You could imagine the music going on in his brain. I guess the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

Back to Top

Professor Herbert Allen, MD, is chairman of the Department of Dermatology at Drexel University College of Medicine. He studied cello at the Juilliard School and science at Columbia University before entering medical school at Johns Hopkins.

Dr. Allen sees definite connections between music and medicine.

My family was musical and we were each encouraged to play an instrument. I started on the violin but found the positioning contorted so I chose the cello instead. I began playing at age 9.

After first studying near my home, I went to study music at the Juilliard School (the college division) with Leonard Rose for four years. He also taught Yo-Yo Ma, who became the number one instrumental soloist in the world. He was in the prep school at the time, about 12 years old, and had his lessons just before me. I wanted to be a soloist, and even though I was very accomplished, I found out very quickly that talent stratifies, especially when you are classmates with Yo-Yo Ma.

Our exams were sheer terror. You would perform solo in front of a jury. Then the jury voted on your performance, and your scholarship was dependent on the jury. Fortunately, it went well for me and I kept my scholarship all the way through.

Halfway through Juilliard, I decided that even though I liked music and the cello, I wasn’t destined to be a soloist. I liked orchestral playing, but not enough to make a career of it. Medicine was in my family, so I began studying simultaneously at Columbia University and ultimately decided to pursue a medical career.

I’m glad that music is still part of my life. My wife is a pianist, and we play together at events such as fundraisers, weddings and funerals. Communicating with the audience through music is really gratifying to me. With a Juilliard background, you are trained as a professional musician, and that carries with it the desire to do a good job. So there is stress as well as pleasure in playing at special occasions. That’s a mindset I think I’ll have till I pass.

I enjoy newcomers to the field — they are really amazing. My vintage is almost gone; musicians such as Itzhak Perlman and Yo-Yo Ma have come to the twilight of their careers. Folks like Perlman are doing more conducting than playing these days. I’ve gone to see Perlman perform. I met him before he was famous. My wife was friends with his future wife. I knew Yo-Yo Ma just as a classmate, but I’ve gone to see him play and have almost all his recordings.

I see definite connections between music and medicine. In both disciplines, you have to stick to a problem and learn to work through it. As a physician, you want to do the best job you can, just as a musician does.

I can also recognize talent — tell who has it and who doesn’t, which is important in music and medicine. For 25 years, I was affiliated with the nationally recognized training orchestra Symphony in C, as the artistic representative on the board of directors. I gave Alan Gilbert his first job, as music director of Symphony in C, and he is now music director of the New York Philharmonic. I also gave Rossen Milanov his first job, and he is still music director of Symphony in C, as well as other highly regarded orchestras around the world.

I recognize talent in medical students and residents when they have a really quick uptake, a pleasant bedside manner, and they’re able to apply what they’ve learned effectively. I admire those who are thoughtful outside the bounds of ordinary things. I keep pushing residents to expand the envelope as much as possible, to consider things that haven’t been thought of before, put them in a new light and see how it goes. This is not much different than what the best musicians do.

Back to Top

An ophthalmologist who is fellowship trained in glaucoma treatment, Brian Chen was exhibiting his work at an Old City gallery when he was a medical student. In fact, before coming east to Drexel, he had already had two shows at UC Berkeley.

Art has always been a very important part of my life. It gives me a creative outlet, and I feel like it balances me out. I do mostly acrylic paintings — just like I was doing in medical school — but since moving back to California [in 2014], I haven’t had a chance to exhibit out here. It’s something I’d love to get involved with. For me, art and medicine always went hand in hand — there are actually a lot more similarities between art and medicine than a lot of people think. In college, when I was doing my molecular and cell biology major, I was an art minor at the same time, so I always thought of them together.

Blossom

I work a lot with my hands in ophthalmology, especially in fine detail. Just treating patients in general takes some selfexpression, just the same way you can express yourself on a canvas (or however you like) with art as well. There are definitely a lot of similarities between the two.

I trained classically in art in college so I did a lot of illustration, sculpture, and installations; but I ended up using acrylics because I liked how it felt. I also liked the vibrancy of the color in acrylics. While I was going through medical school and training, I was also constantly moving around, and acrylics were very portable versus sculpture or oil painting.

Tusk and Pearl

It is definitely not a coincidence that I chose to go into the field of ophthalmology. I feel that everything is interconnected: your eyes help you appreciate art and, at the same time, art helps you appreciate your eyes.

I do a combination of quick pieces and more studied pieces. I am working on something now, and I have a few more pieces I’ve added within the past couple of months. If I can amass a collection, I may try to get a show together.

Back to Top

Herb Rigberg retired from practice as an obstetrician/ gynecologist and became medical director of the Arizona Quality Improvement Organization, Health Services Advisory Group. After 12 years, he retired again, only to return two years later as the organization’s CEO. Five years later, he really retired and found himself becoming a professional artist.

Earlier in my life, I felt I had no time for photography. Then, on a trip to Botswana in 2005, I took a camera because it would have seemed criminal not to. I was so satisfied with the pictures I took, I became tantalized.

My wife and I started to travel more and I took more photos. I began to think, “Anybody can take a picture, but what if I could manipulate the images I took?” I began doing this with bits and pieces of various images I had saved — “mind bytes” preserved in my photographs. I combined and arranged these, using available computer programs. Then I added freehand work to my method, first mapping out compositions and then utilizing photographic bytes to achieve the finished pieces.

Someone who saw my early pieces suggested I offer one for the Phoenix Art Museum Contemporary Art Auction. It sold for $1,500. Moreover, an attendee at that auction turned out to be the curator of the University Hospitals of Ohio art collection. She bought 22 of my images.

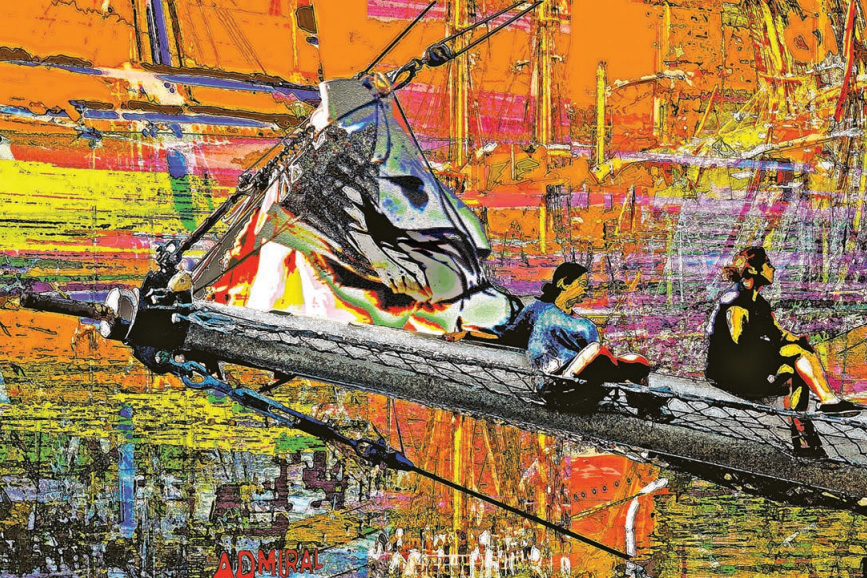

Jib Jam by Herb Rigberg includes elements from a trip to Bergen, Norway, when the tall ships were in. See more of Rigberg’s work on his website: rmdphoto5.com.

Encouraged by the responses to my work, I have begun to spend up to eight hours daily on my photography. Last year I had a show at the Cattle Track Art Compound in Scottsdale. The compound is well regarded for the artists who have worked or exhibited there. I felt honored to have my works there. I am also very pleased that the show did well and I sold several pieces. This year, I have had a show at a new gallery in Scottsdale.

Early in our marriage, my wife’s interest in art drew my attention. The first piece of art we ever bought was from a gallery in downtown Philadelphia. It cost $50. That was the amount on my monthly paycheck. So the dealer arranged for us to buy it over four months. My interest in collecting art took off from there. But for years, I could only enjoy other people’s works. What a kick it is to create my own works as well as to appreciate others’.

There’s a lot of variety in my work. The photographic images I have taken provide the material out of which I complete a new piece. I am most interested in finding and using less-anticipated, less-previously-explored images. To that end, instead of a whole building, I might focus on a water pipe. Instead of a man walking a dog, I might direct my attention on the leash in a hand. I’m really not primarily interested in backgrounds, either. Instead, I go to work constructing my images out of bits and pieces, and occasional hunks, of my own photos. I have thousands of images I have used. I actually like to reuse images. I can alter them so much they are hardly recognizable. Or I can change them only slightly.

Tango, by alumnus Herb Rigberg, is composed of what the artist calls "mind bytes."

I love color. I don’t care if colors are keyed to reality. I don’t mind if they clash as long as they work for me. The nice thing about working on computer is how easy it is to make physical alterations. The terrible thing about working on computer is the almost infinite number of choices and changes available. Right now, I am thinking about hand-coloring and drawing on computer-generated images. I recently saw a wonderful photographic exhibit in which the artist used hand-tinting as part of her method.

What similarities are there between art and medicine? My dad was a physician, and a graduate of Hahnemann Medical School. To people of his era, doctors practiced the ART of medicine. Now things have changed. If my generation became bound by rules, guidelines and protocols, this generation perceives medicine itself almost entirely as a science. Still, the necessity for discipline defines both then and now, medicine and art. Art, conceptually, may seem boundless and without discipline. But the more I work at it, the more I discover that discipline is central to success in both medicine and art.

Back to Top