Civil Rights Exhibit at Hagerty Library Highlights Youth's Role

By Frank Otto

By Frank Otto

Just in time for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a new exhibit focusing on the role of youth in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s opened at W.W. Hagerty Library.

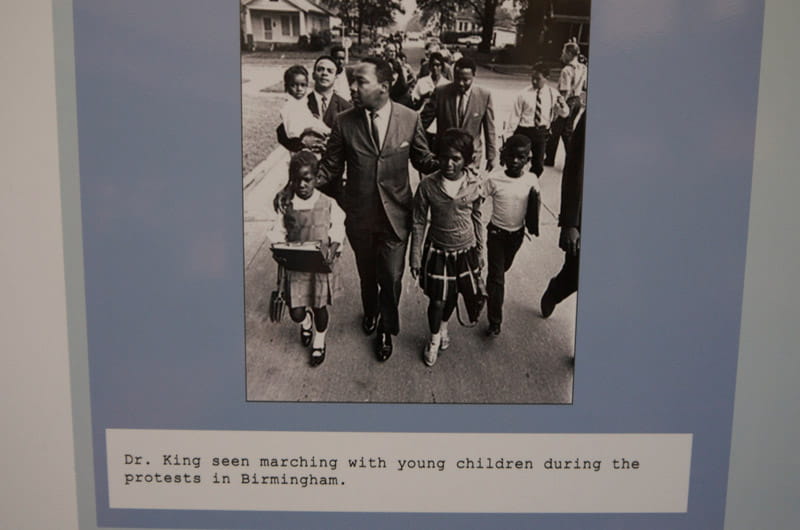

Unveiled Thursday night, Children, Youth and Civil Rights, 1951–1968: A Student’s Exhibit highlights how children and teenagers spurred campaigns for civil rights during the time when King and other historic leaders were active.

Developed by students of V.P. Franklin, a former Drexel professor now holding a presidential chair and serving as distinguished professor of history and education at the University of California, Riverside, the exhibit has traveled the country and even been displayed at the U.S. Capitol Building’s visitor center. It will be at Drexel until Feb. 13.

“This combines two things that are valuable to the Drexel community — an historical view of the civil rights movement but also evidence that students and young people have tremendous power to influence change,” said Danuta Nitecki, PhD, Drexel’s dean of libraries.

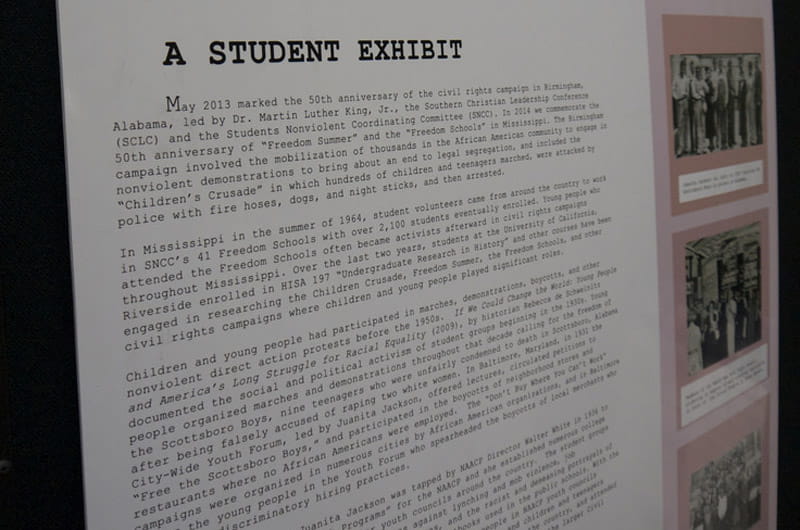

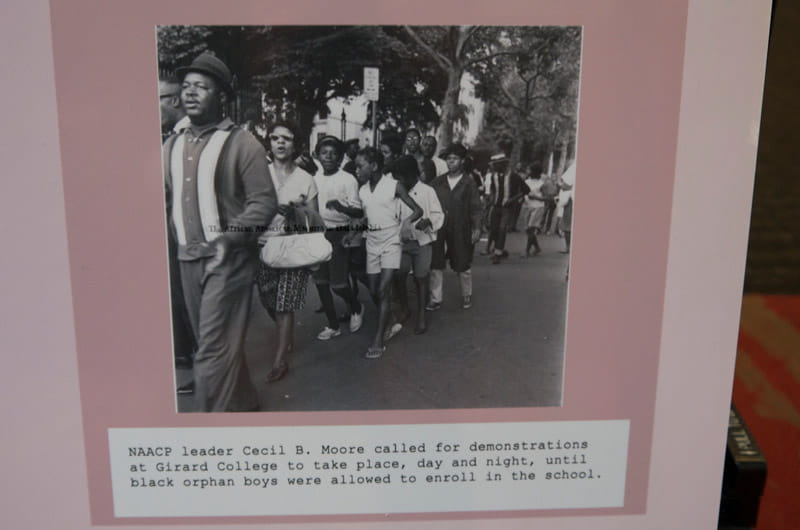

Events such as the 1963 Children’s Crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, 1964’s Freedom Summer, and the desegregation of a high school by the “Little Rock Nine” are among the topics covered by the exhibit through the use of photographs, newspaper articles, political cartoons and other periodicals from the time.

In conjunction with the opening of the exhibit, a lively panel discussion featuring professors from Drexel as well as community leaders was held Thursday night.

Titled “Civil Rights: From Mississippi Freedom to Ferguson,” events from the exhibit were discussed and parallels were drawn to current situations.

“We’re thrilled that Drexel Libraries is able to partner with other groups on the campus to host an informed, stimulating discussion that will provide a venue for continued conversation about race relations and civil rights in America,” Nitcecki said.

English Professor André Carrington, PhD, whose expertise includes race, participated in the panel.

"These are good opportunities to learn from people who advocate for civil rights within and outside the University's walls, like Nayo Jones and Taylor Johnson, who are clearly using their education in the fight for social justice," Carrington said. "It's also an opportunity to translate ongoing conversations about racial justice into action through the material we teach in our classes, as faculty, and the decisions we make at an institutional level regarding diversity, inclusion and empowerment."

The exhibit Franklin's students put together elicits strong emotions in Carrington.

"I feel compassion and also anger, frankly," Carrington said of taking it in. "It is hard to see the difficulties that young people endured just trying to enjoy their childhood — to see the extremes that all-white communities went through to keep black children from attaining a quality education, going so far as to burn elementary schools to the ground to shut down public education entirely rather than see it integrated. It reminds me that it's the work of our current generation to reverse the harmful impact of racism on our society."

Parallels between what Carrington sees in the exhibit and what he sees in the current racial and cultural climate jump out at him.

"Dr. King's last campaign, the Poor People's Campaign in which he was mobilizing sanitation workers at the time he was assassinated, is as relevant now as it ever was," Carrington said. "The white/black wealth gap is still very much intact because wealth has been passed down and grown along racial lines for generations, just as poverty and debt have remained disproportionate burdens on the same communities that were impoverished throughout the 20th century."

Franklin feels the exhibit has special relevance to today’s young people.

“Given the lack of resources in public schools, the emphasis on ‘high-stakes testing,’ the decrease in well-paying employment opportunities and crushing student debt, children and young people today are as oppressed, or more oppressed, than their counterparts in the 1950s and 1960s,” Franklin said. “The exhibit focuses attention on what was accomplished in the past so that we can learn lessons about what could be accomplished in the future.”

In light of that, he hopes those who take in Children, Youth and Civil Rights, 1951–1968 may take some inspiration.

“I believe that once children and teenagers in the millennial generation learn more about the social activism and moral positions taken by children and teenagers in the past, it can serve as an important precedent for young people’s activism today,” Franklin said.