Art of the Syllabus

Syllabus Content

Both minimalist and maximalist approaches to syllabus design have their proponents: concise syllabi are easier to navigate, while detailed ones offer a more precise picture of the course structure. Regardless of the approach, all syllabi need to include a set of essential components:

- instructor contact information

- content overview

- course learning goals/outcomes

- course schedule

- course materials

- assignment and grading schemes

- relevant academic policies

A syllabus should also include information about institutional services and supports available to students facing academic struggles, mental or physical health problems, food insecurity, bias or discrimination, and other challenges that may affect academic success. Highlighting the availability of institutional support systems helps de-stigmatize support-seeking behavior and connect students to the resources they need. Drexel University faculty are advised to use this checklist of required syllabus components when crafting their syllabus.

Many syllabi also include a diversity statement and/or a land acknowledgement to signal commitment to a just and inclusive learning environment. It’s important that the values expressed in such statements inform other aspects of the course (content curation, theoretical frameworks, faculty-student communications, course policies, course assessment schemes, etc.), so that the statements do not become mere performative gestures.

Instructors can help students understand syllabus components by taking care to frame them in a meaningful way. For example, most syllabi list office hours, but very few students attend. A syllabus can encourage students to take advantage of office hours by explaining their function and usefulness, offering flexible office hour formats, or even requiring an initial mini-conference. Similarly, simply linking an official academic integrity policy may not be enough, as the concept of “plagiarism” can be interpreted differently by different students based on educational experience and cultural background. Explaining what academic integrity means in individual disciplines and courses helps students understand syllabus rules in a broader context. For example, the best AI policies explain the rationale behind the restrictions and allowances, linking them to the course’s learning goals.

Check out related teaching tip on clarifying academic integrity expectations [requires Sharepoint Login]

Check out related teaching tip on developing an AI course policy [requires Sharepoint Login]

Syllabus Tone

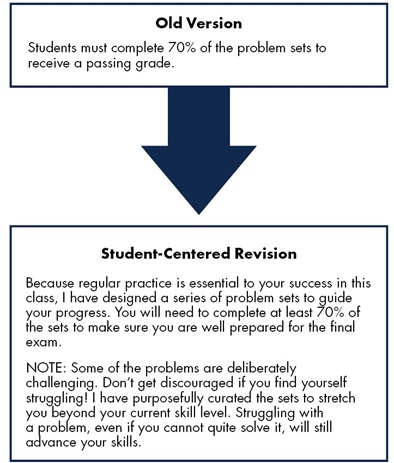

Academic syllabi have traditionally been written in a dry, legalistic tone (“students must complete 70% of the problem sets to receive a passing grade,” “failure to cite sources will result in an automatic loss of ten points”) but research shows that small changes in tone can make a big difference in student perceptions of the syllabus, the professor, and the course. For example, the statement about problem sets could be revised in the following way:

This expanded version includes elements of metacognition (explaining how learning works) as well as a much more personal, warm tone. Faculty who do not have the option of editing their syllabi can craft a syllabus cover letter to accompany the official program document.

Check out related teaching tip on using psychologically attuned language. [requires Sharepoint Login]

Inclusive Syllabus Design

Ensuring diversity in syllabus design involves not only curating diverse content but also attending to questions of diversity in the course’s theoretical, epistemological, and methodological frameworks. An inclusive syllabus signals awareness of larger social realities and power structures that may affect student educational experiences, and communicates respect and support for students experiencing marginalization or discrimination. A syllabus can communicate support for all students by:

- representing a diversity of voices and perspectives

- demystifying academic rules and processes

- avoiding legalese and jargon

- humanizing the professor

- expressing confidence in success for every student

- clearly communicating how to succeed in the course

- lifting the veil by articulating the “hidden curriculum” (unspoken rules governing academic expectations and culture)

Inclusive syllabi ask students to be co-creators rather than passive recipients of their education. To this end, students may be invited to:

- bring their lived experiences and knowledge into the classroom

- co-develop class policies

- help craft learning outcomes

- vote on ground rules

- exercise choice in readings, assignments, and assignment modalities

- design collaborative course projects

- offer feedback to the professor

Finally, inclusive course policies take into account the complexities of student lives, allowing for flexibility and agency, and avoiding inflexible, overly disciplinarian approaches.

Innovative Syllabus Formats

Alternative syllabi formats, used either as a replacement or as a complement to the traditional syllabus document, can increase accessibility, help students navigate syllabus content, and establish rapport. Alternate formats can also be used for parts of the syllabus to create interest and emphasis.

- Q&A syllabus: instructors can make the syllabus more user-friendly by replacing traditional section headings (“course materials,” “absence policy,” “grading”) with student-centered questions (“What will I need to buy for this course?” “What if I need to miss a class session?” “How will my work be evaluated?”) followed by answers. The benefit of this approach, besides improved readability and searchability, is that it invites professors to answer questions in a more natural, informal voice.

- Graphic syllabus: Graphic syllabi offer an immediate visual representation of how the different sections of the course relate to one another, helping students gain a deeper and longer-lasting understanding of course material.

- Liquid syllabus: students increasingly access course information on mobile devices. Mobile-friendly liquid syllabi offer learners an accessible entry point into the course.

- Living syllabus: for the technologically adventurous, an exciting option is the living syllabus, an interactive site that includes links, maps, timelines and other tools for student engagement.

- Course “trailer”: a course trailer is a video supplement to the syllabus proper, or an embedded component of a liquid syllabus, in which the instructor introduces themselves and the course to prospective students. While some course trailers feature professional-level video editing and advanced graphic elements, a simple amateur video works best to establish rapport and welcome students to the class.

Getting students to read the syllabus

Even the most beautifully crafted syllabus will not do its job if the students don’t read it. To avoid the familiar frustration (“It’s on the syllabus!”) instructors can replace the traditional first day of class syllabus read-through with a number of alternatives:

- The non-linear overview: students skim the syllabus (individually or in groups) and identify sections they want to discuss. This interactive approach not only breaks up the monotony of the standard syllabus overview, but also offers insight into student priorities.

- Syllabus jigsaw: students read and discuss sections of the syllabus in small groups, and then reshuffle to teach others material from their respective sections.

- Syllabus speed dating: after reviewing the syllabus individually, students sit in two concentric rows of chairs, facing one other student at a time. The student pairs ask each other two questions, one syllabus-related and one personal. After a brief interval, the student pairs rotate.

- Syllabus scavenger hunt: students search for specific information on their syllabi.

- Syllabus email: students respond to the syllabus in a short introductory email to the professor.

- Hopes and fears: after reading the syllabus, students compile a list of hopes and fears about the course.

- Collaborative syllabus editing session: students revise, expand, or vote on any parts of the syllabus that lend themselves to negotiation. Following this initial conversation, faculty share a revised, final version of the syllabus.

Check out related teaching tips on preparing students for your course with preview week activities. [requires Sharepoint Login]

Next: Innovative Course Design