Steps to Build a Culture and Process for Peer Review of Teaching (PRT)

Establishing a peer review of teaching process and community culture is not easy and takes time. Following recommendations from literature, research, and colleagues can help. A synthesis of this work suggests following a few basic steps including: sharing goals and addressing faculty concerns, developing a process and protocol for peer review, selecting or creating instruments, preparing reviewers, and continuing to adjust the process for further improvement.

While there are many documented benefits of peer review, it is important to acknowledge and address faculty reservations. Common objections to peer review include the time it takes to implement it, concerns about unintended consequences, and anxiety about opening teaching to critique. Peer review is most effective when faculty see the usefulness of the process to their professional growth, and are involved from the start. Before jumping in, we recommend laying some groundwork by assessing faculty readiness, clarifying goals, and inviting ongoing contribution.

Actions to take:

- Share broad goals for creating a peer review of teaching process

- Provide background research about peer review of teaching

- Bring in faculty speakers who have experience as a reviewer or reviewee

- Facilitate small group discussions about potential benefits and reservations about peer review

- Nominate or elect credible faculty leaders with knowledge of evidence-based teaching to lead the process of drafting and developing the protocol and instruments

- Promote an open and transparent culture that values teaching

Resources to use:

There is not a single correct process for engaging in peer review of teaching (PRT). Literature on PRT includes several recommendations. The process that you develop should take into consideration the specific needs, goals, and cultures within the disciplines and academic units where PRT will take place.

A formal PRT statement and protocol clarifies questions about the PRT process such as:

- What are the purposes of the peer review of teaching program (formative development, documentation for merit increases or promotions, contract renewals, etc.)?

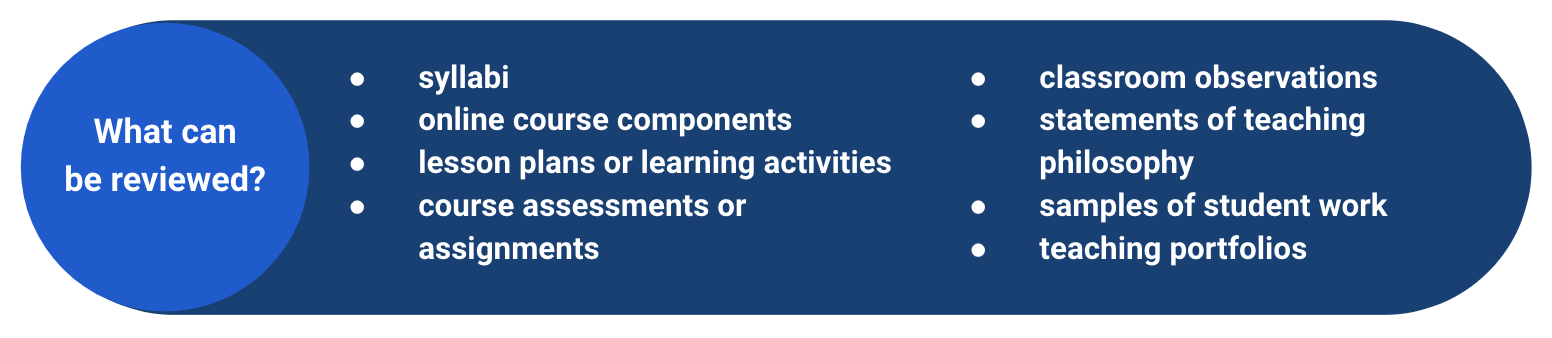

- What areas of teaching will be reviewed (classroom observations, syllabi, teaching portfolios)?

- How will the evidence be collected?

- Which faculty members will be reviewed?

- When and how often will the review(s) be conducted?

- Who will the review(s) be conducted by?

- How will the review be documented?

- How will the PRT process be monitored?

While the specific protocol can be customized to the context, PRT should always consider multiple elements of teaching. To provide a more valid, holistic view of an individual’s teaching, materials and observations should be collected from multiple sources, over time, using multiple methods. For these reasons, teaching portfolios that examine teaching through multiple perspectives are considered a gold standard in PRT. A teaching portfolio (or dossier) is a curated and organized collection of materials that documents an individual's teaching practice. Because faculty select the contents and provide the framing and narrative comments, teaching portfolios offer more control over how individuals represent themselves and their teaching. Teaching portfolios also provide an opportunity for faculty to reflect on their beliefs about teaching, examine assumptions about students' learning, and set future goals.

Did you know? Student evaluations of teaching may be one useful data point, but they should never be the only evidence of teaching effectiveness considered. Growing evidence of identity bias in student evaluations must be considered when using student evaluations in PRT.

Teaching Observations

While peer review of teaching should always consider multiple aspects of teaching, if possible, observations of teaching are important to include within PRT.

A protocol for peer reviews, especially teaching observations, typically follow the following format:

- Pre-observation meeting to discuss the goals and context for the review.

- Teaching observation or material review using predetermined instruments.

- Post-observation meeting to discuss feedback.

- Written summary by reviewer (optional).

- Written reflection by reviewee.

Actions to take:

- Form a committee or working group to lead the process

- Clarify values and goals for peer review

- Review examples of departmental, school, and/or college peer review protocol

- Provide opportunities for faculty input and feedback on protocol drafts

- Use feedback to drive protocol revisions

Resources to use:

- Defining Effective Teaching and Understanding our Lens, Endeavor Foundation Center for Faculty Development, Rollins College

- Example of Institutional Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness, Center for Teaching Excellence, University of Kansas

- Creating a Narrative of Professional Involvement (CANOPI), Office of Faculty Advancement, Drexel University

- Example Departmental Protocol for the Peer Review of Teaching, Office for Faculty Excellence, North Carolina State University

- Developing a Protocol for Peer Review of Teaching, North Carolina State University, ASEE Conference

- Peer Review of Teaching Protocol, Office of Instruction and Assessment, University of Arizona

- Peer Review Procedure, Department of Human Physiology, University of Oregon

- Example Pre-Observation Meeting Questions, Faculty Innovation Center, University of Texas at Austin

- Example of Post-Observation and Debriefing Questions, Center for Teaching and Learning, Oregon State University

- Example Written Reviews and Reflections, College of Arts and Sciences, Washington State University

Definitions of teaching excellence can vary extensively between faculty. And, as with all evaluative processes, there is some degree of subjectivity within peer review of teaching. Therefore, in order to achieve more consistent, relevant, and equitable feedback, it is essential to use instruments in the peer review process. An instrument is a tool that helps ensure reviewers are using specific, measurable criteria for evaluation and feedback. The activity of developing or selecting peer review instruments can help faculty within a department, school, or college converge their ideas about teaching effectiveness. All instructors should be aware of and have access to peer review instruments at all times, not only at the time of review.

Instruments can be selected, adapted, or created from scratch. The instruments used may also vary depending on the purpose of the review, the course type, and the modality. For example, a different instrument might be used for a teaching observation in a didactic course then one used a lab. One instrument may be used for in-person observations, then a different one used for the review of online courses. Instruments can range quite a bit, but typically they include checklists, rubrics, and open-ended prompts.

Questions to guide you in the development or selection of instruments for peer review of teaching:

- What are observable criteria of effective teaching?

- How can we articulate standards for various elements of effective teaching?

- What general or discipline-specific research and standards can we draw from?

Actions to take:

- Facilitate small group discussions about teaching effectiveness

- Review examples of peer review instruments for different course modes and types

- Review research on effective peer review instruments

- Charge a committee or working group with selecting or drafting instruments

- Provide opportunities for faculty input and feedback on instrument drafts and revisions

Example instruments for various course types and modalities:

Example instruments for specific disciplines and/or pedagogical goals:

- Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM Classes (COPUS), Wieman Science Education Initiative, University of British Columbia

- Student Engagement Observation Protocol (BERI) for quantitatively measuring student engagement in large university classes Wieman Science Education Initiative, University of British Columbia

- Teaching Practices Inventory Self-Assessment, Wieman Science Education Initiative, University of British Columbia

- Inclusion by Design Syllabus Checklist, Center for Faculty Innovation, James Madison University and Research Academy for Integrated Learning, University of the District of Columbia

- Online Course Quality Review Rubric (OSCQR), State University of New York

- Syllabus Rubric and Scoring Guide, Center for Teaching Excellence, University of Virginia

Providing effective and equitable peer review of teaching requires thoughtful preparation, even for the most seasoned college instructors. Literature on peer review suggests all reviewers, especially those who were not part of the process of selecting or developing an instrument, should prepare before providing a review. Peer review of teaching experts recommend conducting mock reviews where small groups of faculty use the selected instrument to review the same syllabus, course materials, or recorded teaching observation and then discuss their review. During this process, reviewers can practice providing feedback to colleagues and consider ways to deliver constructive feedback. Mock reviews help reviewers identify if their feedback is more extreme than that of their colleagues (overly positive or negative), which creates more consistency across reviews. The mock review process can also unearth problems with the instrument or reveal the need for clarification regarding terminology and standards, leading to important recalibration.

Actions to take:

- Determine who will be providing peer reviews

- Facilitate mock reviews to test and calibrate instruments

- Share best practices for providing peer reviews and delivering feedback

- Provide opportunities for reviewers to practice delivering feedback

Resources to use:

- Preparing reviewers for formative peer observations, Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of British Columbia

- Recommendations for pre-observation meetings, Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of British Columbia

- Preparing for a pre-observation meeting (for reviewees), Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of British Columbia

- Recommendations for post-observation meetings, Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of British Columbia

- Guidelines for providing and receiving feedback, Center for Teaching and Learning, Oregon State University

Developing a peer review process should not be considered a “one and done” undertaking. The protocol and instrument(s) should be reviewed on a regular basis with input from reviewers and reviewees. While no process will be perfect, building in opportunities for regular revision can help to develop trust in the process over time. It can also increase the effectiveness of peer review and allow the process to adapt to emerging pedagogical research and innovations.

Check out Drexel University Case Studies of PRT