Microscopic Algae Hold Key to New Jersey’s Nutrient Pollution Now and in the Past

By Frank Otto

By Frank Otto

By finding out what kinds of microscopic algae are present in coastal lagoons, scientists can get an important look into the conditions of these ecosystems — both in the present and past.

Scientists from the Academy of Natural Sciences took samples of sediment from salt marshes at both Barnegat Bay and Great Bay in New Jersey to try to determine whether the tiny algae, called diatoms, were reliable gauges for eutrophication — the presence of excess nutrients.

“We found that in coastal wetlands of New Jersey, diatoms are sensitive to the amount of nitrogen contained in the sediments,” said Marina Potapova, PhD, assistant curator at the Academy and an assistant professor in Drexel’s College of Arts and Sciences. “Some species are associated with nitrogen-poor environments, while others proliferate in nutrient-polluted wetlands.”

Potapova was one of the co-authors on the study which was published in the Journal of Coastal Research. Nina Desianti, a PhD candidate at Drexel, served as the lead author.

Elevated concentrations of nitrogen can be harmful to ecosystems since they can lead to “blooms” of phytoplankton. These blooms can deplete oxygen levels in the water and be dangerous to other forms of life, such as fish.

High levels of nitrogen — as well as other minerals — are now becoming unnaturally common due to human activity, such as farming. Rains wash nitrogen out of fertilizers in fields and the nutrients end up in bodies of water such as Barnegat and Great bays.

As such, having a sound indicator like diatoms is invaluable for ecologists.

“Biological indicators not only tell us about the kind and degree of pollution, but inform us on the effects of this pollution on living organisms and ecological processes,” Potapova explained.

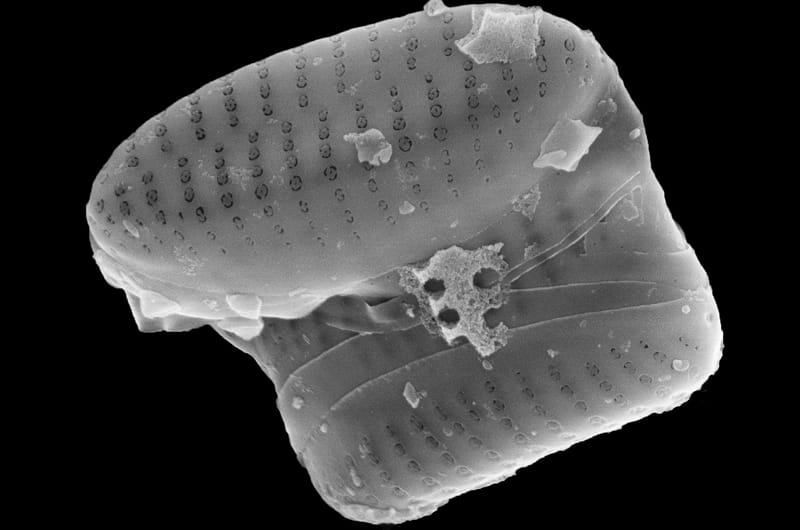

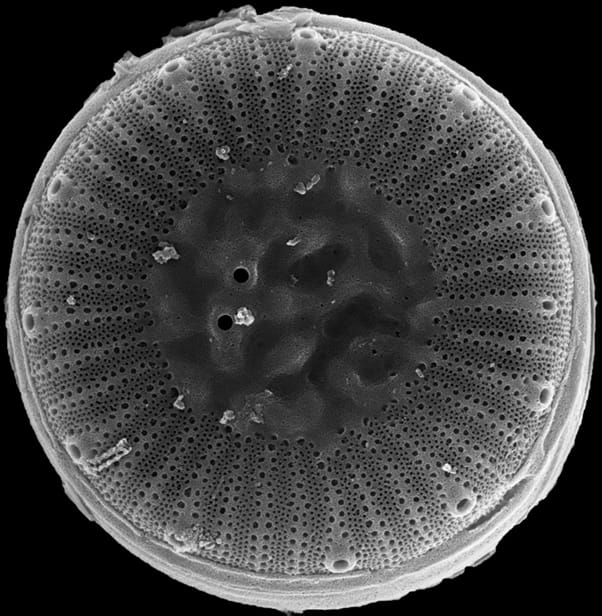

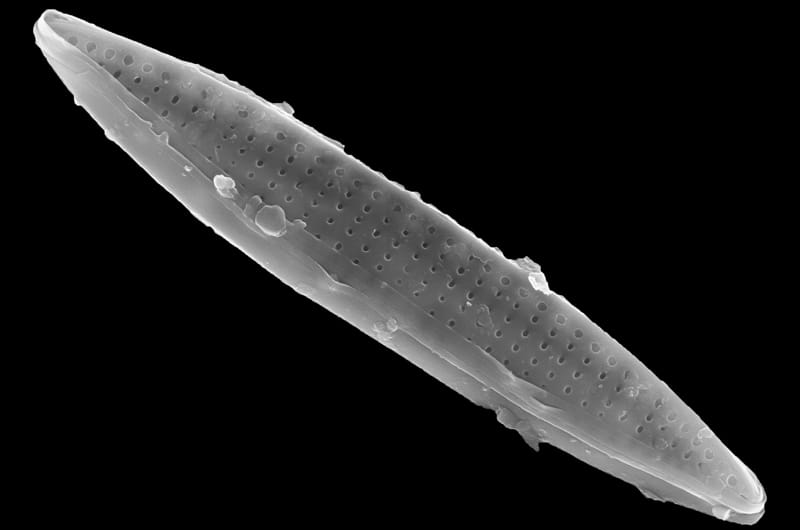

The Academy-led study team found that high numbers of diatoms such as Fragilaria amicorum, Cyclotella choctawatcheeana and Nitzschia frustulum were good indicators of high nitrogen levels.

But the diatoms were not only good bio-indicators for nitrogen levels. They were also pretty reliable in determining how salty the water in the bays were. So, of the three species named above, F. amicorum and C. choctawatcheeana were both especially present when nitrogen levels were high in water with a low level of salt (salinity), and N. frustulum was present in eutrophic waters with high salinity.

“Most aquatic organisms prefer to live at certain salinity levels, so when salinity changes, biological communities also change: some species disappear and others replace them,” Potapova said.

Diatom specimens are also dependable indicators of past conditions, as they can be preserved in the sediment.

“Salinity in coastal wetlands depends on many factors, such as the amount of freshwater brought by the rivers and streams, the intensity of water exchange between bays and the open ocean, the sea level and configuration of the coastline,” Potapova said. “Knowing salinity preferences of various diatom species, we can reconstruct how salinity was changing in the past and, thus, reconstruct the environmental history of the coastal regions.”

Moving forward, Potapova and her collaborators hope to piece together their data on nutrient and salinity preferences in diatom species to find out how water quality in the area changed over the last few centuries, since human activity significantly ramped up.

“We are also exploring whether diatoms may help to reconstruct the history of salt marsh destruction and re-establishing after coastal storms,” Potapova said.

Those interested can read the study, “Sediment Diatoms as Environmental Indicators in New Jersey Coastal Lagoons,” here. The study was co-authored by David Velinsky, Roger Thomas, and Jerry Mead, all of the Academy; and Mihaela Enache and Thomas Belton of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.