Jatra With Me

January 28, 2019

Jeffrey Stanley, Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, is a 2018-19 Fulbright-Nehru Scholar researching early 20th century film and theatre in the state of West Bengal and its impact on India's nascent independence movement. While in India he is also developing collaborative projects with the Bangalore Little Theatre and the Viveka Tribal School in rural Saragur. For more information on his work, please see his bio following his article.

“I am the part-producer of this opera. I have another three operas.” Kolkata ad man Kanak Bhattacharya was giving a recap of his years working in jatra, a form of traveling folk theatre native to West Bengal and the surrounding regions of eastern India. About 20 years ago, Kanak started work as a producer of TV series for Bengali television. He had no professional theatre background, and his journey into jatra had a unique start.

“I was doing very well in television,” he said, “but in 2005 I thought, why not try jatra? And I thought, we have sponsors for TV series, so why not sponsors for jatras?” He pitched his visionary idea to several corporate advertisers until he found one willing to take the chance on what was seen at the time as a dying art form. He paired the advertiser with the Ratnadeep Opera. The result, he says, was a huge financial success. Soon he was being asked by other jatra companies to find more corporate sponsors willing to take the plunge.

For many American readers, and even many Indians, who don't know, jatra means journey. Jatra opera is a form of traveling musical folk theatre that's been around for centuries in West Bengal and environs. It has its roots in ancient Sanskrit theatre, but it’s recognized founder, or at least perpetuator, was Sri Chaitanya, a 16th century Hindu mystic and spiritual reformer who preached Vaishnaivism, or the worship of Lord Vishnu as Hinduism’s foremost deity.

Vishnu’s chief incarnation is Lord Krishna. Most Americans first encountered this unique brand of Hinduism in the 1960s when it came to the US and took organizational root as ISKCON, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, more commonly known as the Hare Krishna movement.

Four-hundred years previous, Chaitanya was seen by the Hindu mainstream leadership as a troublemaker who preached blasphemy. Religious authorities frequently harassed him and his followers, destroying any temples or monasteries they erected. Because Chaitanya was preaching his new spiritual path to a chiefly impoverished and illiterate rural audience, he turned to educational theatre to convey his sermons, enacting mythological stories from the life of Krishna to teach the lessons of the Bhagavad-Gita.

When the pressure got too great, Chaitanya followed in the footsteps of many wandering prophets before him ranging from Jesus to the Buddha: he took his show on the road. He brought his disciples and their theatre accoutrements with him, and the jatra opera was born.

By taking this step, Chaitanya and his followers were doing two things—teaching Vaishnavism in an entertaining way to isolated lay audiences, and keeping one step ahead of the law. The law won. Stories of his disappearance read like a tragedy ripped from today’s headlines about the demise of Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi. In 1534, while ministering in the city of Puri in what is today the eastern Indian state of Orissa, he walked into the city’s ancient temple to Lord Jagannath, an incarnation of Vishnu, and never walked out. Devotees believe his spirit merged with that of Jagannath and that he literally disappeared. Skeptics suspect he was killed and his body either dumped in the nearby ocean or hidden inside the temple. This story gained credence in 2000 when the Architectural Survey of India discovered an ancient skeleton hidden inside a temple wall. Some have concluded that it was the remains of Chaitanya.

Jatra plays were originally devotional in nature but have evolved over the years to explore other stories from Hindu mythology, the biographies of historical figures including Napoleon and Adolph Hitler, and even to address modern social problems, especially those plaguing rural communities.

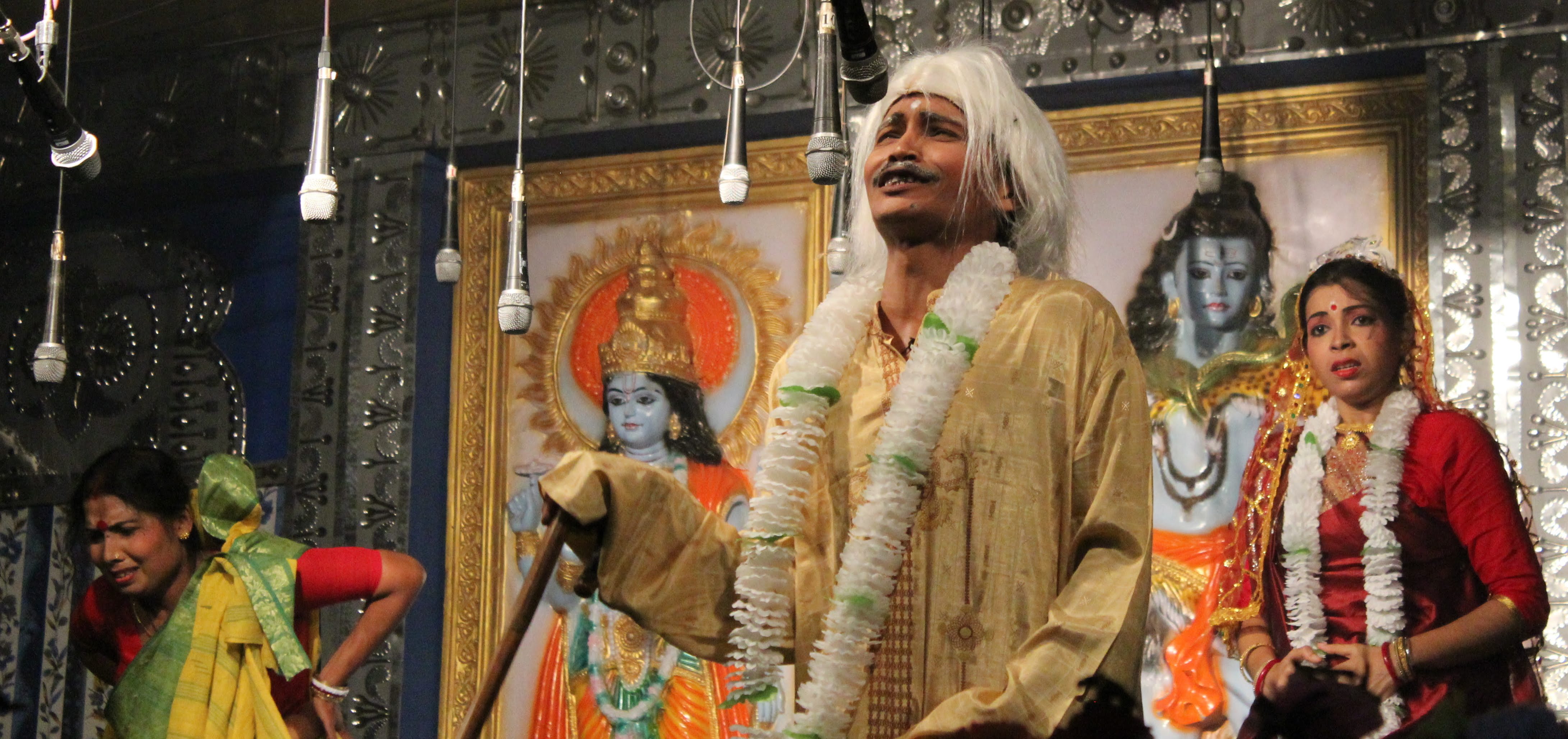

In its current form, some elements of jatra have remained intact while others have fallen by the wayside. The tiny, portable stage is still the same, and is still used ingeniously to allow for rapid scene changes. It can be a mountaintop, a front porch, a riverbank, or two locations miles apart with two scenes happening simultaneously.

The music is performed live using a mix of folk instruments like the tabla, dhol, and wooden flute, combined with modern synthesizers and an electronic drum pad. The musicians are following what Western academics would call a "jazz aesthetic," meaning it's improvised during rehearsals, and the musicians play off of each other with the input of the director. The musicians take notes for future reference but there is no printed score. The brash notes, drumbeats and melodies, sometimes sweet and sometimes jarring, are used to heighten a character's private moods and express them to the audience moment to moment. And forget the orchestra pit. In true, albeit coincidental, Brechtian style, the musicians sit lined up on the left and right sides of the stage performing in full view of the audience.

By design the acting and gestures are extremely overwrought, reminiscent of Japanese kabuki in style. Likewise, the light changes happen rapidly and constantly as part of the expressionistic emotional cues to the audience about a character’s feelings. In a flash there may be a strobe effect, or the entire stage will be bathed in deep red or blue for a few seconds before flashing back to normal.

A veritable vineyard of mics hangs from a bamboo grid mounted above the tiny stage. They’re mixed and processed live by the sound designer who makes much use of reverb and other effects on key lines of dialogue. The speakers are cranked up to 11. It's intentionally loud and brassy to match the actors’ exaggerated postures and dialogue, so that the show can be seen and heard by an outdoor audience ranging typically from 2000 to 5000 villagers. The nearly 3-hour show is a nonstop assault on their eyes, ears and hearts.

These intense light and sound innovations were first tried by writer-directors like Purnendu Shekar Banerjee, who advertised one of his shows in the 1970s as featuring “jatrascope,” and famed Marxist actor Utpal Dutta who had already made a name for himself on Kolkata’s mainstream theatre stages before trying his hand in the hinterlands with jatra.

According to scholar Prabhat Kumar Das in his 2014 book Jatrar Songe Bere Otha (“Growing Up With Jatra”), Dutta himself said in the 1970s that the greatest actors and actresses in Bengal were working in jatra, but he defended his use of technology as necessary in keeping with the times, much to the chagrin of jatra purists. It was the struggling coal miners and farmers, Dutta said, who wanted the shift from mythological stories to social dramas about Lenin and Mao. Jatra taught new actors how to reach thousands of people, said Dutta, in order to take theatre from Kolkata’s educated elite to the rural working classes.

Kanak agrees with Dutta’s assessment. “Because of the huge encroachment of TV series, people are used to seeing glamorous actresses and actors onscreen,” he said. “So we have to take those actors away from TV and put them in jatras to bring the audience out.” To rural audiences who don’t live near movie theaters and can’t afford streaming platforms like Neflix India and Amazon Prime, television still rules supreme, and so do TV stars. “Nowadays, every TV actor wants to come to jatra,” he said, “because jatra is giving them fame and money.”

Throughout the late 1970s into the new millennium, jatra seemed to be in its death throes. Songs were lifted from popular Bollywood films and storylines were blatantly copied from movie plots. That disheartening trend began to change in 2011 when West Bengal’s current Chief Minister, Mamata Bannerjee, was elected to office as the first woman to hold the post. A die-hard liberal and lover of the arts, she quickly imposed a series of changes intended to save jatra. Nowadays, the state sponsors an annual jatra festival and awards ceremony in Kolkata. Pension payments for impoverished jatra actors saw a 50% increase.

“The government has made it very easy for us in other ways,” explained Kanak. “In the past, the jatra company had to pay up to 70,000 rupees for an extra police detail if the show featured a big TV star. But Mamata's government took it down to 5000. She has also sharply reduced the tax on ticket sales.” Her government has also created a booklet on jatra groups and the new regulations, and distributed it to police and district judges throughout rural areas. Tickets typically cost 50 to 100 rupees, representing an affordable range for economically disadvantaged audiences.

With such good prospects, Kanak couldn’t help but wade further into jatra’s waters after his initial successes. Today he’s the sole owner of one company and part-owner of three others, including the aptly named Sri Chaitanya Opera, which started in 2015. He balks at those who claim that jatra is dead. “For 34 years it was dying, dying, dying. After 2011, jatra gradually improved. I had a show extend its run to 200 nights last year,” he said proudly. “It’s an all-time record.” He hopes to beat that record this year.

Why has jatra remained popular among the working class? “Firstly, it has a social message always,” said Kanak. “It's always easy to convey any kind of message through jatra. In the villages we are very welcome. Plus, it's really great that although in Bengal there is a scarcity of work, jatra employs a lot of people. A typical jatra company employs 50 people including cast, musicians and crew. If a worker has a four-person family waiting at home, then a single company is feeding 250 mouths. With his hands in four companies, he boasts that he helping put food on the table for 1000 people, and in the always-struggling performing arts, no less.

He also takes a producer’s pride in the fact that he has snagged one of only two women directors working in jatra today, Ruma Dasgupta, who is also a well-known jatra actress. “When I started in jatra I always wanted the best,” he said. “I got the best actors and then I wanted the best director. And even these big TV stars said we are fine with Ruma.” She directed two of his current three productions this season and there are more in the pipeline for next year.

Kanak also credits himself with discovering the next generation of jatra talent, including 24-year-old ingenue Tapashi-Moon, who has a huge following on social media. She’s only been acting in jatra for four years, three of which have been with Kanak’s companies. “This year I gave her the lead role and she's doing very well,” he said. “Tapashi is young, jovial, has a strong public presence and her own fan base. Outside of jatra she’s known as a poet and reciter of poetry. She is a very good actress, there’s no doubt about it.” This season’s ticket sales prove that Tapashi-Moon is a hot ticket. Next season, Kanak hopes to snag her as the lead in a production by the Ratnadeep Opera, of which he is now the sole owner.

Speaking as a foreign playwright, performance artist and teacher, it’s my strong belief that if an organization like the Wooster Group in New York City performed a modern jatra opera at St. Ann's Warehouse, with the likes of the legendary Elizabeth LeCompte and company's throaty breathing and love of technology, and they didn't change a thing except to perform it in English, jatra would likely be seen as cutting edge experimental theatre here. Perhaps a bold professional company in Philadelphia will rise to my challenge. Jatra is a truly dynamic form of performance art, and it deserves an international audience.

Many thanks to Mr. Debadip Majumdar for translating the book Jatrar Songe Bere Otha and serving as interpreter during my interview with Mr. Bhattacharya.

Jeffrey Stanley (third from left) backstage with actors Subhayu Mukherjee, Dibakar De and Tapashi Moon.

Jeffrey Stanley (third from left) backstage with actors Subhayu Mukherjee, Dibakar De and Tapashi Moon.

Tapashi Moon, Bengali film star Dulal Lahiri, Ruma Dasgupta and Subhayu Mukherjee.

Tapashi Moon, Bengali film star Dulal Lahiri, Ruma Dasgupta and Subhayu Mukherjee.

Ashok Banerjee and Biswajit Majhi.

Ashok Banerjee and Biswajit Majhi.

Timir Mondal.

Timir Mondal.

Light board operator Atanu.

Light board operator Atanu.

Jeffrey Stanley

Jeffrey Stanley

Jeffrey Stanley is a 2018-19 Fulbright-Nehru Scholar researching early 20th century film and theatre in the state of West Bengal and its impact on India's nascent independence movement. While in India he is also developing collaborative projects with the Bangalore Little Theatre and the Viveka Tribal School in rural Saragur. Stanley's stage play Tesla's Letters (published by Samuel French, 2000) premiered to rave reviews Off Broadway and has gone on to continued national and international productions.His award-winning short film Lady in a Box starring Sarita Choudhury has been licensed numerous times for international broadcast and distribution. He has been a fellow at Yaddo, a Copeland Fellow at Amherst College, and a guest screenwriting lecturer at the Imaginary Academy in Croatia sponsored by the Soros Foundation. Stanley was one of 24 writers chosen from over 16,000 entrants for the first Amtrak Writers Residency, and his work has appeared in the Washington Post, New York Times and other publications. He holds an MFA in Dramatic Writing from New York University Tisch School of the Arts and a BFA from Tisch in Film & Television Production. He is an adjunct faculty in Westphal's Screenwriting & Playwriting program as well as at NYU Tisch.