The power of old fashioned (“little”) data

By Ana Diez-Roux, MD, PhD, MPH

Dean, Dornsife School of Public Health

Posted on

November 17, 2015

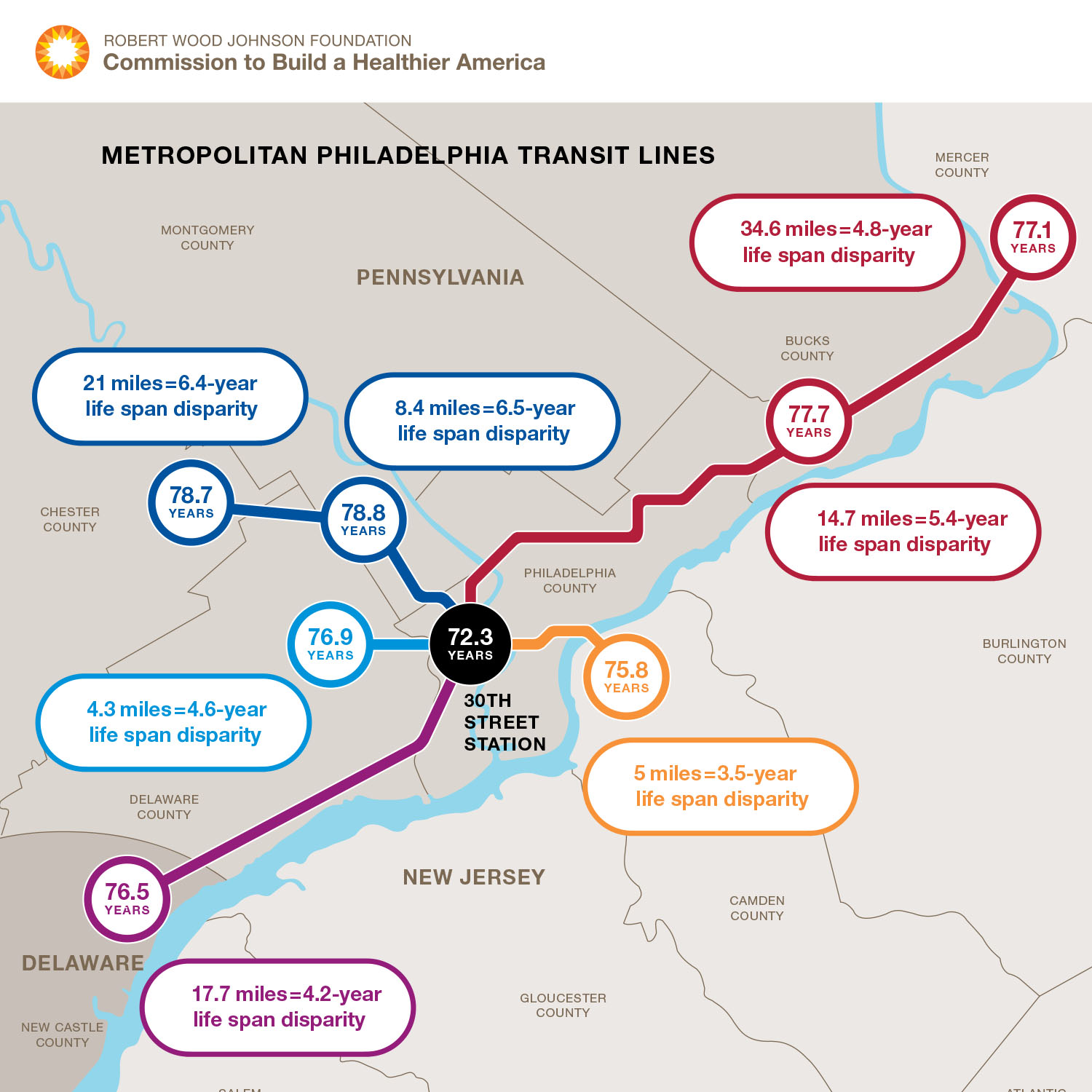

More recent analyses have documented remarkably large differences in life expectancy even across spatially proximate neighborhoods within cities, including our very own Philadelphia.

At a time when there is so much talk of the promise of “big data” it is sobering to see the striking patterns and findings that can emerge from “simple data”, and the classic approaches of demography and epidemiology that have formed the basis of public health for centuries. Just over the past few weeks, two studies reported extensively in the media have demonstrated the insight that can be gleaned from the simple analysis of mortality data (NY Times: Death Rates, Declining for Decades, Have Flattened and NY Times: Death Rates Rising for Middle-Aged White Americans).

Researchers with the American Cancer Society used federal mortality data to study trends in longevity between 1969 and 2013. To their surprise they found that the marked decline in death rates that had been occurring for decades flattened substantially between 2010 and 2013. The researchers attributed this flattening to the effects of the obesity epidemic on heart disease, stroke and diabetes-related mortality, although the reasons are still the subject of debate. The stagnation in death rates was more pronounced for women than for men. These gender differences are consistent with prior research showing that the recent evolution of mortality has been especially unfavorable in women, for reasons that have not been fully elucidated.

In another recent paper two economists at Princeton University reported actual increases in mortality rates since the late 1990s among middle aged whites living in the United States. Remarkably this increase was driven by increases not in the traditional big killers of cardiovascular disease, cancer and injury related mortality but by troubling increases in suicide and the consequences of drug abuse, including alcohol and drug poisoning as well as chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. More detailed analyses showed that the mortality increase was confined to whites with a high school education or less (in whom death rates increase by a remarkable 22% between 1998 and 2013) whereas whites with a college education experienced a decline in death rates. Of note, although declining over the entire period, death rates for middle aged Blacks remained substantially higher than death rates for whites, a fact that was not as extensively reported in the press. The increase in death rates in whites with low education was consistent with declines in inflation –adjusted income and increasing reports of pain, poor health, and distress in this group over the same period.

Taken together with two recent Institute of Medicine Reports on the unfavorable evolution of health and mortality in the United States compared to other high-income countries over the past few decades, these mortality studies raise important questions about health in the United States and its drivers. These are not the first studies to demonstrate the large differences in health status and death rates across social and demographic groups. Nearly 10 years ago, a study that also used existing mortality data reported a striking 20 year difference in life expectancy across the best off and worst off of the “eight Americas” (groups created by cross-classifying race/ethnicity, gender, and county of residence). This large difference was observed comparing Asian women to high risk urban Black men. More recent analyses have also documented remarkably large differences in life expectancy even across spatially proximate neighborhoods within cities, including our very own Philadelphia.

The fact is that these big patterns are often hiding in plain sight. Remarkably, we often fail to focus on them and when we stumble on them we struggle to find compelling explanations. And yet these are the big problems we in public health should be focusing on. It is unlikely that sophisticated clinical trials or targeting of treatments using the tools of the newly fashionable precision medicine will do much to address these major trends. As pointed out by Geoffrey Rose three decades ago, mass diseases have mass causes. It is our job to disentangle these mass causes and promote a discussion and analysis of the social and policy implications of what we find. Clearly there is much we may be able to learn from meaningful analysis of the detailed and rich “big data” that is increasingly being collected for various purposes all around us, but it is important to remember that major trends, and the big problems in population health, can often be detected through the relatively simple (albeit clever) analysis of the “little” data (like death records) that societies have compiled for over a hundred years.