Principles of Course Design

Integrated Course Design

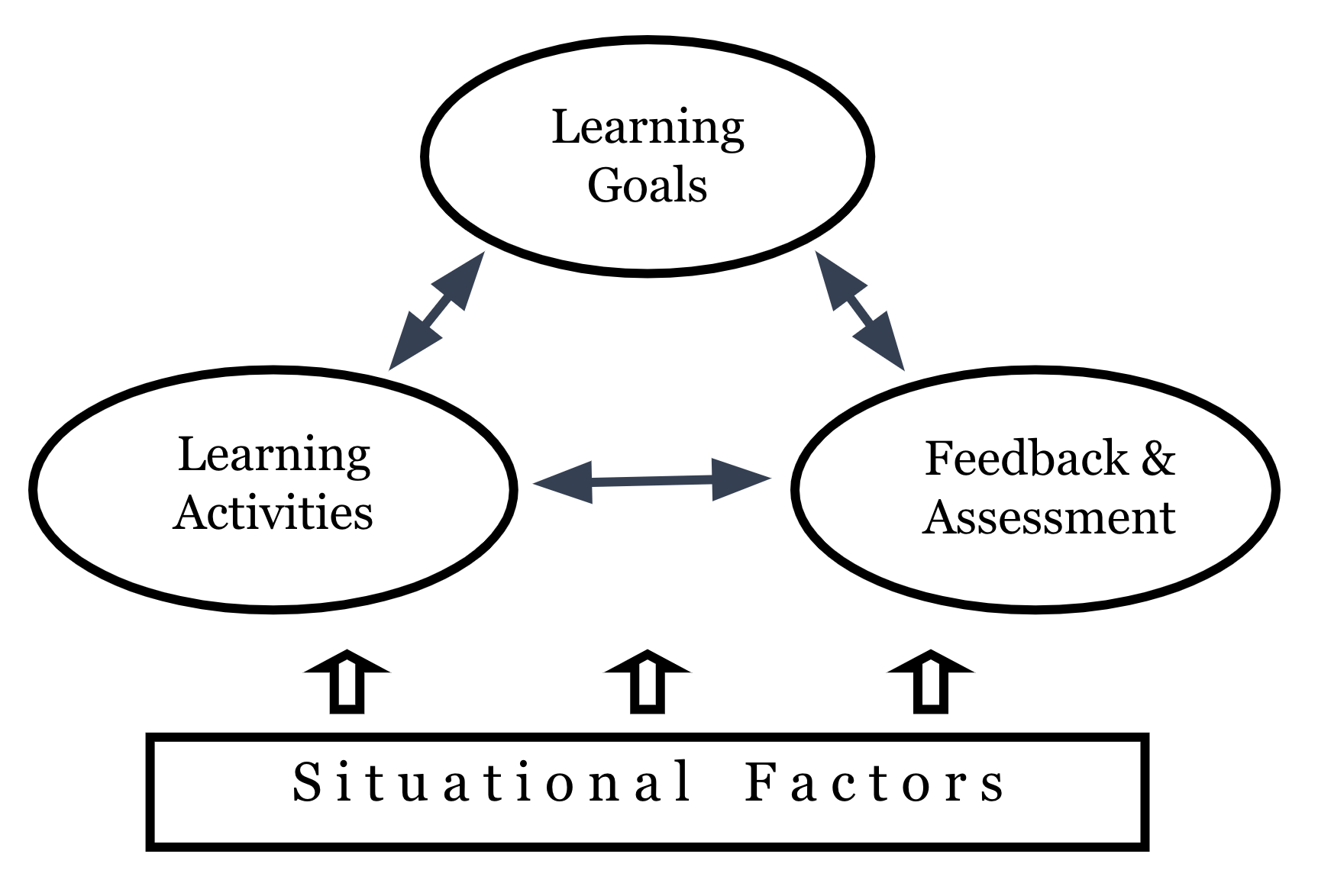

One of the most robust backward design models developed for higher education is L. Dee Fink’s integrated course design. Fink outlines a streamlined process for designing academic courses, divided into three stages:

- The initial preparatory stage involves identifying situational factors specific to each course (class size, student body makeup, curricular level, etc.); articulating course learning goals; designing assessments; selecting learning activities; and ensuring alignment between all of the primary components.

- The intermediate stage involves creating a thematic structure for the course, selecting instructional strategies, and integrating the overall structure and learning strategies into a cohesive scheme

- The third and final stage of the design process involves developing the grading system, debugging possible problems, writing the syllabus, and making plans for evaluating the course.

This systematic process allows instructors to think strategically about each component of their course design, creating deeper alignment between course pedagogy and content.

Crafting Learning Goals

Learning goals are the lynchpin of intentional course design. Well-designed goals can help focus the content curation process, align course components, improve transparency, and track student progress. While the terms “learning goals,” “learning objectives,” and “learning outcomes,” are often used interchangeably, the terms “goals” and “objectives” provide a learning roadmap, while the term “outcomes” names the demonstrable knowledge and skills acquired by the students. A further distinction is that the term “goals” is typically used at the course level and “outcomes” at the unit/assignment/lesson level. Some syllabi include both course learning goals/objectives and corresponding learning outcomes, but most instructors choose to focus on one set only.

A key aspect of course learning goals is that they are observable, so they can form the basis of the course’s assessment scheme; to this end, instructors tasked with crafting learning goals for a course are advised to use “measurable” action verbs (for example “students will be able to apply feminist theory to analyze contemporary children’s movies” or “students will be able to select appropriate methodologies in order to solve problems”).

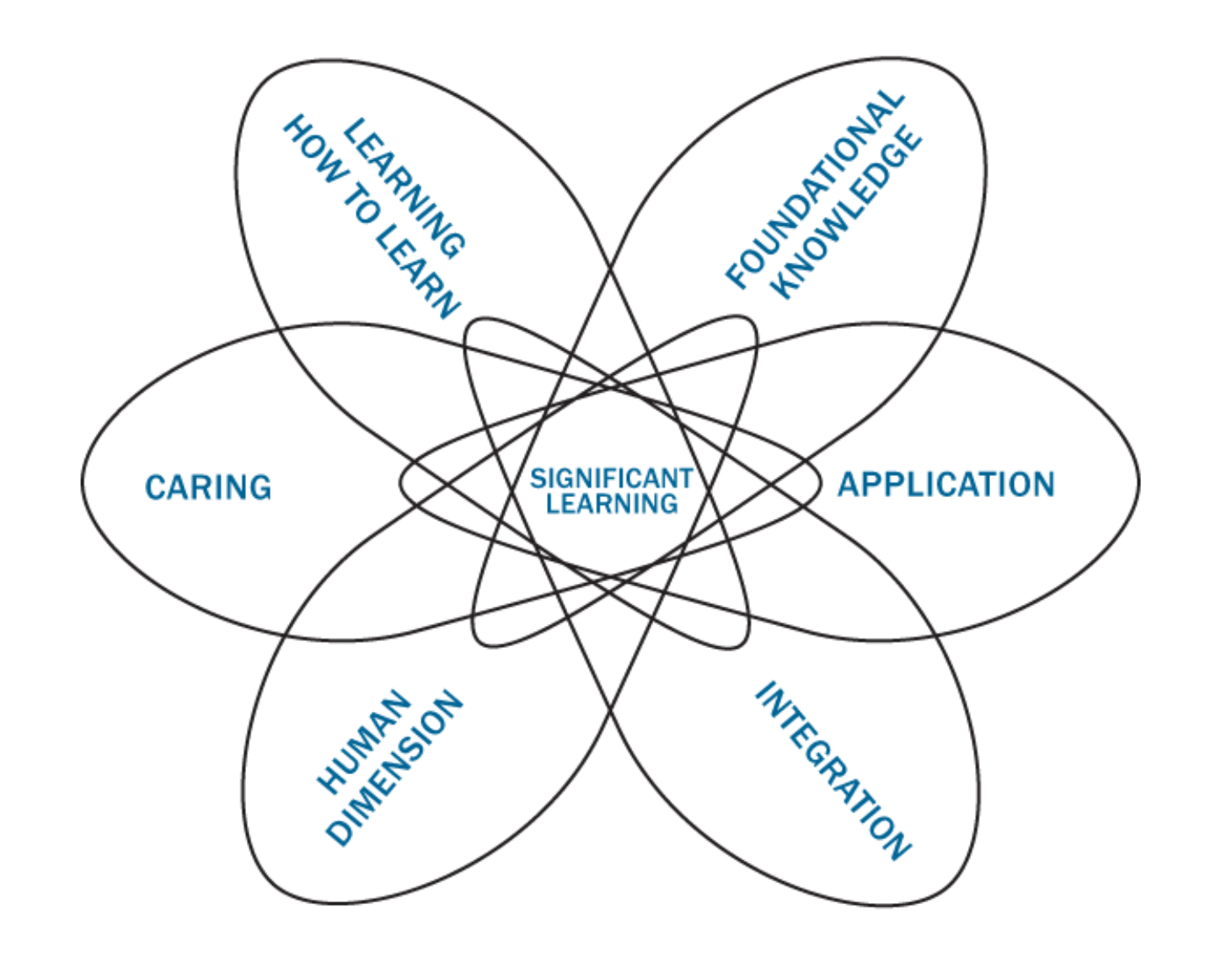

L. Dee Fink recommends developing learning goals that integrate multiple dimensions of significant learning, which, in Fink’s taxonomy, includes not only foundational knowledge (the focus of traditional course design), but also:

- application

- integration

- caring

- the human dimension

- learning how to learn

Ideally, each learning goal will include multiple dimensions of learning. For example, “students will understand the basics of climate science” focuses exclusively on the acquisition of knowledge but “students will be able to communicate the urgency of the climate crisis to non-academic audiences within their own communities” integrates knowledge with application, care, and the human dimension of learning. Similarly, the goal “students will write college-level essays” focuses on the acquisition of an academic skill, but the revised goal “students will be able to develop individualized processes for drafting and revising college-level essays based on each student’s strengths” enriches the original goal by adding elements of integration and learning how to learn.

Designing for Deeper Learning and Transfer

Designing an academic course involves hard choices about allocating the most scarce and precious of resources: time. While instructors are often driven by the desire to include as much content as possible, research shows that prioritizing depth over breadth leads to more effective and long-lasting learning. Rather than packing courses to capacity with new content (emphasis on “coverage”), optimal course design includes ample time for retrieval practice, trial-and-error, formative feedback loops, and reflection. An investment of time is also needed to establish and sustain the class community, given that social belonging plays a key role in student motivation, engagement, and persistence. Finally, instructors should budget time for practicing component skills required for the successful completion of course assignments, such as presentation or collaboration skills, to avoid penalizing students for gaps unrelated to course learning goals, and to help all students transfer skills acquired elsewhere into a new context.

Principles of intentional course design also apply at the micro-scale of the individual class (a.k.a “lesson plan”). For example, a well-designed session might include the following elements in addition to instructor-focused content-delivery:

- a warm-up activity to help students transition into the space of the class

- a curiosity-sparking opening to captivate student attention

- direct instruction that includes clear signposting and draws connections to previous course content and out-of class applications

- opportunities for active and collaborative learning

- practice and feedback opportunities to test real-time learning

- unrushed reflection time

While each course and each lesson plan will follow its own format, good course design involves intentionality and alignment at every scale, as well as built-in mechanisms for ongoing reflection and refinement.

Designing for Transparency

A transparent syllabus includes well-designed learning outcomes but also clear pathways towards achieving them. Explaining the logic behind the course’s organization, mapping out assessments, and communicating assessment criteria helps students understand what they are working towards in each part of the course, and to plan their efforts accordingly. Unlike experts, most novice learners lack an understanding of how various aspects of content relate to one another. Faculty can help students develop a clearer sense of the course’s underlying schema by explicitly communicating it on the syllabus. Graphic syllabi, concept maps, timelines, and flowcharts can be helpful in making the underlying course design more transparent. Students can also create their own visualizations of the course structure on the first day of class, adding new elements at the end of each content unit. Understanding the course schema helps students learn more deeply, make meaningful connections between concepts, and transfer learning to new contexts.

Transparency in course design includes communicating how much time students are expected to dedicate to coursework outside of class. Experts are rarely good at estimating the time needed by students to complete course tasks, so tools like the Workload Estimator app can help get a more realistic picture of the course’s time demands. Transparency regarding workload and time management can help all students, but especially the growing number of learners juggling competing demands of academic, professional, and care work.

Instructors can also use the syllabus to communicate the course’s pedagogical approach in order to reassure students that each learning activity has been deliberately designed to help them achieve course learning outcomes. Assuring learners that they are in the hands of a thoughtful, intentional educator is especially important for courses featuring new modalities or innovative design, where students might be asked to step outside of academic comfort zones and learn in new ways. Transparency about pedagogical design can also help instructors establish trust and rapport, preempting student push-back and/or disengagement.

Reflection and values

While course design theory focuses on structure and alignment, instructors are much more than efficient content-conveyors or skill-coaches. The work of teaching is often accomplished through unscripted exchanges and impossible-to-measure moments of human connection. Driving these less tangible dimensions of academic teaching are the core values that instructors hold dear but do not often have the time to articulate. Making time to reflect on the values that underpin our teaching can also feed back into individual decisions about course design. For example, if you value intellectual risk-taking, build in rewards for creative failure into your grading schema; if you value community, dedicate time to community building; if you believe diversity strengthens academic disciplines and institutions, integrate diverse content, epistemologies, and pedagogical approaches into your course. Taking time to align teaching practices with deeply-held values at every level opens up new possibilities for transformative pedagogy and societal transformation.