Behind Philadelphia's Soda Tax

How Philadelphia became the first big city to pass a soda tax

Copyright: Signe Wilkinson, Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer

Copyright: Signe Wilkinson, Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer

November 15, 2016

by Paul Jablow

To pass a soda tax in Philadelphia, politics and public health quietly joined

forces. It was an odd pairing: Politics frames life in black and white, with competing

constituencies vying for power and influence in a world of limited resources

and all-or-nothing choices. In contrast, public health embraces connections and

nuances - recognizing how the elements of well-being are intertwined,

influencing each other and our quality of life for better or worse.

The outcome of the unusual partnership was a new revenue stream to fund pre-K

education, and provide health services in nine schools in poor neighborhoods –

with the side-benefit of possibly improving overall health in the city that

made cheesesteaks famous and obesity is becoming commonplace.

HOW IT HAPPENED

When he took office in January, Mayor James Kenney knew that

passing a tax on sugary beverages in Philadelphia was regarded as a long shot.

No major city had ever passed such a measure, and attempts had been thwarted more than 40 times around the country. His

predecessor, Michael Nutter, had twice failed to get City Council to approve a

sugary-drink tax, often referred to as a ‘soda tax.”

Even Kenney, then a councilman, had opposed it: “He didn’t feel

the revenue was going to clearly define, accountable initiatives,” according to

his spokeswoman Lauren Hitt.

A month after Kenney’s inauguration, Tom Farley became

Philadelphia’s health commissioner. He was very familiar with the idea of a

soda tax because he and his boss, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, had been

stymied twice on such a tax and once on a more modest plan to ban jumbo

containers for sugary drinks. Labeling their proposal an “obesity tax” didn’t

help.

Farley arrived in town skeptical about the chances of achieving

one of his long cherished goals. Mayor Kenney was ready to try again, but with

a novel strategy: Most of the $91 million generated by the soda tax would go to

pre-K education, and to designated community schools in poor neighborhoods,

along with funding parks, recreation centers and libraries. Rather than an

unjustifiable burden or a prod to force healthy behavior, the tax was framed as a necessity.

“We knew if we led with (health benefits) we’d be defeated,” says Kevin Feeley, spokesman

for Philadelphians for a Fair Future, a coalition of some 80 civic, labor and

faith organizations. Pre-campaign polling showed that “we had to tie it to programs that resonated with voters and with

elected officials.”

In June, a “thrilled” Farley joined Kenney, other local officials and health

advocates around the country in celebrating Council’s passage of a 1.5

cent-per-ounce tax on a variety of beverages. The tax, which the American Beverage

Association (ABA) is challenging in court, includes not only sugary drinks such

as sodas, sweetened teas and sports drinks, but also artificially sweetened

beverages such as diet sodas.

The final vote was 13-4, with opposition coming from the three Republicans in Council

and a Democrat, Maria Quinones Sanchez, whose district includes a Coca-Cola

bottling plant and numerous bodegas.

“A soda tax was fairest because it was a tax no resident or small business had to pay,”

Hitt says, “unlike wage or property taxes.”

Prior to the big-city win in Philadelphia, only one other similar soda tax measure had

won approval – passed by referendum two years ago in smaller Berkeley, CA. A

recent study there found that consumption of sugary drinks was down 20 percent

in some neighborhoods, significant reductions that researcher Kristine Madsen

at UC Berkeley says could, if maintained, reduce rates of obesity and Type 2

diabetes.

The two successes have encouraged public health advocates to hope

that the tide is turning so that sugary drink taxes could become as widespread

and accepted as cigarette taxes. On November 8, four additional communities successfully passed soda tax proposals: San Francisco, Oakland, and Albany in California, along with Boulder, Colorado. (NOTE: The online version of this story has been updated to reflect election results)

Farley believes that New York’s failed efforts contributed to

Philadelphia’s win almost a decade later. “Over the years we succeeded in

getting people to recognize that this is a health problem we ought to do something about,” he says. “When we started with this work ...

people viewed foods, but not beverages, as fattening. Now everyone knows that

sugary drinks increase their risk of obesity and diabetes, and people are

shifting away from them.”

THE OPPOSITION

The basic pro-tax campaign strategy was to have coalition members

lobby members of Council. “Spending a lot of money on a citywide campaign

wouldn’t have accomplished very much,” says Feeley. “We needed nine votes on

Council, that’s all.”

Anti-tax forces led by the American Beverage Association relied on

lobbying by small grocers and the Teamsters Union, whose members deliver bottled

and canned beverages, and on a publicity campaign that described the measure as

a “grocery tax.”

The beverage association spent $10.6 million and the coalition,

$2.5 million –actually a large war chest for a pro-tax campaign, with over half

the cash coming from billionaire Bloomberg. Nationally, according to an

analysis by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the ABA, Coca-Cola

Co. and PepsiCo have spent $67 million since 2009 trying to defeat initiatives in 19

states. Federal lobbying the tally.

Larry Ceisler, a spokesman for the beverage industry in the campaign, discounted the

loss in Philadelphia as a sign of things to come. “What happened in Philadelphia was very particular to Philadelphia,” he says. “This was not an ideological

decision but a transactional decision.

“The mayor was able to use the full force of his office to trade favors for votes.”

On September 14, the beverage association, some businesses and residents sought an

injunction in Common Pleas Court stating that the tax, scheduled to go into

effect Jan. 1, violates the Uniformity Clause of the Pennsylvania Constitution,

which requires that similar products be taxed at the same rate. The city has

allocated $1.6 million to retain two former city

solicitors to lead the defense. Calling the sweetened-beverage tax “a political

choice of necessity,” lawyers for the city have asked the state Supreme Court

to dismiss the lawsuit.

ON THE HORIZON:

A Day in Court… and Change

In a news conference following passage of the soda tax, Kenney

said, “This is the beginning of a process of changing the narrative of poverty

in our city.” That’s a very “public-healthy” declaration from a politician.

Philadelphia has the highest rate of deep poverty among the

nation’s 10 largest cities. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014 Annual

Community Survey, 186,000 Philadelphians – including 60,000 children – live on

$12,000 per year, about half of the federal poverty level of $24,000 for a family

of four. Poverty, obesity, access to education and health services are intertwined

variables –key social determinants of health and well-being. Poor people also

consume more sugary drinks than the affluent,and are disproportionately affected by health problems associated with excess calories,

including obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

The soda tax revenue will not only help prepare young children for school success, but

also teach them and their families to live healthier lives and, in the selected

community schools, improve access to health services.

The value of pre-K has been well established for decades. Starting with a cohort of

at-risk students from 1962-1967, the HighScope Perry Preschool Study showed

that pre-K returned $17 for every dollar invested for such benchmarks as

income, high school graduation and incarceration.

The beverage-industry lawsuit notwithstanding, preparations are underway by

Philadelphia to offer 2,000 pre-K slots to 3- and 4-year-olds in January and gradually build up to 6,500.

The Mayor’s Office estimates that there are 15,000 kids in what would be considered

“quality” day care and maybe another 17,000 with providers who don’t meet that

standard. The goal is for all providers to meet state standards, which would

include a health curriculum – or to replace them.

Cheryl Bettigole, who heads the city Health Department’s Division of Chronic Disease

Prevention, says the nine community schools funded by the soda tax will get

coordinators to work with parents, students and the public on health-related issues.

The Health Department is partnering with the University of Pennsylvania and Johns

Hopkins University on a three-year study of the tax’s impact on price and consumption.

Whatever the outcome of the beverage-industry lawsuit, awareness that less sugar is good

for your health is taking hold – even in the industry itself.

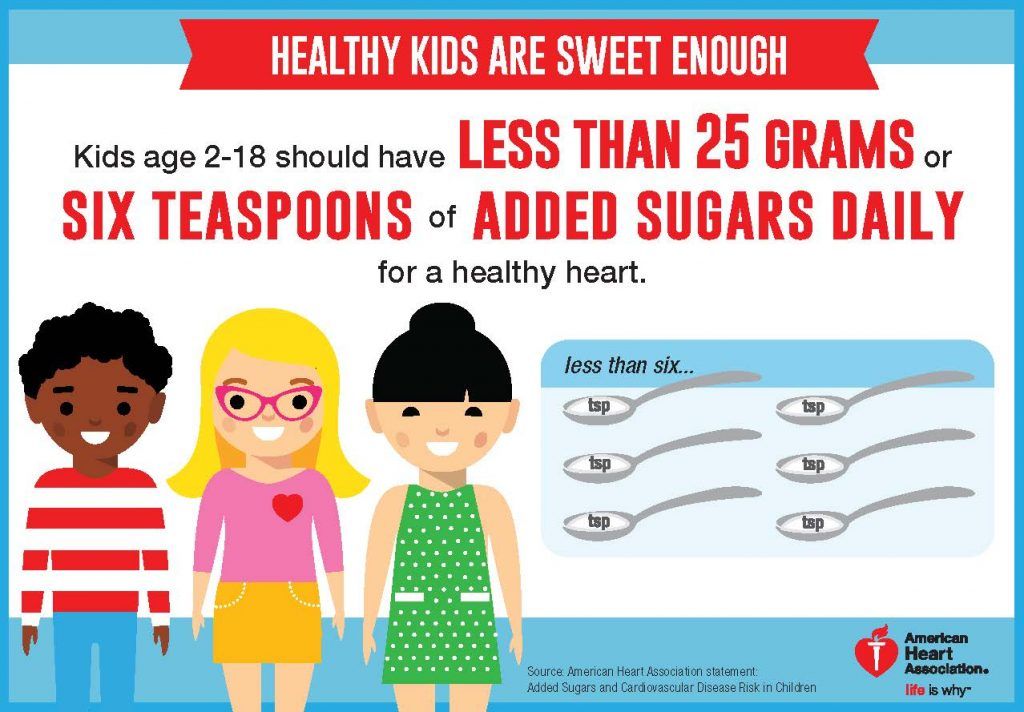

The American Heart Association recently released its first-ever guidelines on sugar

limits for children to less than six teaspoons of added sugars a day.

And a September New York Times story revealed that historical documents showed the sugar industry paid scientists in the 1960s to downplay

the link between sugar and heart disease, and to promote saturated fat as the culprit.

American Heart Association Recommendations Limit Sugar Consumption for Kids

For Children and Teens ages 2 to 18: No more than 1 cup of sugary beverages per week

Children and teens should consume

less than 6 teaspoons of “added sugars” a day and drink no more than 8 ounces

of sugary beverages a week, according to an article by the American Heart

Association’s (AHA) on its first-ever scientific statement recommending

specific sugar limits for kids. Published in the journal Circulation in August,

the AHA statement also said that children younger than 2 shouldn’t have any

added sugars, but instead have nutrition-packed diets for growing healthy

brains and bodies.

Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, MD,

president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, endorsed the AHA

recommendations. “Reducing the amount of added sugars children consume is one

of the smartest, most effective strategies we can pursue to reverse the

national childhood obesity epidemic,” Lavizzo-Mourey said in a statement.

“Parents, policymakers, industry leaders, health advocates, and all share the

responsibility for ensuring that this guidance swiftly becomes a part of our

national nutrition fabric.”

The beverage industry has already removed full-calorie soft drinks from U.S.

schools, and is developing lower-sugar products. PepsiCo reports that 45

percent of its revenues come from lower-calorie to fully sugared sodas.

In Philadelphia, water stations in public schools will be installed district-wide

by the end of the school year. Students can fill water in containers as well as

sip from a fountain.

“As a society, access to very cheap sugary drinks shouldn’t be our focus,” says Amy

Auchincloss, PhD, MS, associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology and

Biostatistics at the Dornsife School of Public Health. “They’re not necessary for well-being and, in fact, can have harmful consequences.”