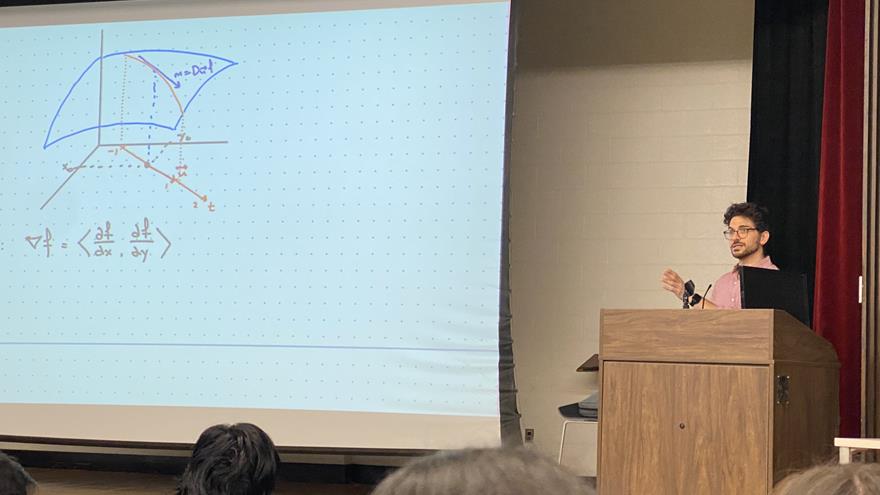

Meet Dimitrios Papadopoulos, Recipient of Inaugural Provost Teaching Award for Undergraduate Teaching Impact

By Natalie Kostelni

During his junior year at Ridley High School in Delaware County, Dimitrios Papadopoulos, EdD, was terrified of his AP calculus teacher, Mrs. Crosby, who he described as “pretty intimidating.”

Despite this youthful perception, Mrs. Crosby has since become a lifelong inspiration for Papadopoulos, his career as a math professor and the way he approaches teaching. This lasting impact came during a seminal moment in AP calculus when he asked Mrs. Crosby a question about a problem. She acknowledged she didn’t know the answer and would need time to figure it out.

Mrs. Crosby gave the class the same problem to work on as she sat off to the corner trying to solve it. She returned a few minutes later with the answer and relayed that the solution was not intuitive.

“That was one of the most informative moments in my entire educational career and shaped how I think about education more than anything else,” Papadopoulos said in a recent interview. “Mrs. Crosby had an attitude that we’re here to learn together even though we have different roles. She was insistent that the classroom was a learning community.”

Papadopoulos, associate teaching professor of mathematics in the College of Arts and Sciences, has been teaching at Drexel since 2010 and has established his own reputation for cultivating community.

“I have acted on instincts rooted in my experiences as a student and the methods and attitudes of the teachers I admired,” he said. “I identified a common thread in these teachers: the ability to model sustained inquiry and to foster a sense of community in the classroom.”

In 2023, Papadopoulos was among four Drexel faculty recognized for implementing outstanding innovations in teaching and learning with the inaugural Provost Award for Undergraduate Teaching Impact. The award recognizes full-time faculty who have made a distinctive impact through excellence in teaching, primarily at the first- or second-year undergraduate level.

“My teaching philosophy centers on two values: curiosity and empathy, and I really feel they are intertwined,” he said. “To be empathetic is to be genuinely curious of another person’s experience. I have worked hard to try to put myself in the perspective of a student who doesn’t understand something. If I want our students to be curious about mathematics, I ought to be curious about how they learn, what they struggle with, what the assessments I give actually reveal, and what assumptions I bring to my work.”

In this interview, Papadopoulos shared his journey to becoming a math professor and the experiences and research that shaped his teaching philosophy.

What led you to become a math professor?

As an undergraduate at Temple University, I was undeclared for two years, but always loved math and was good at it from the time I was a little kid. I owe that to my grandfather who told me that if you could learn math, you could learn anything. He would sit with me after school and we would build different things together and that felt akin to the problem solving of math. I always had a desire to learn how things work and the characteristics of math as a mode of inquiry. I ended up majoring in math. After working for nearly two years, I started grad school at Drexel and had an assistantship. On my first day, I was handed a textbook and told I was teaching pre-calculus the following Monday. Within minutes of starting to teach, I knew that this was it. I connected with it immediately.

Why is it important the classroom serves as a learning community?

Math is a subject that challenges many students, not just intellectually but also emotionally. The classroom is a learning community where each member has a role and mistakes are to be celebrated as learning opportunities. When students feel that the classroom is a community to which they belong, their attitudes and academic performance improve. My approach to fostering a sense of community begins with a view of the teacher not as a vessel for content, but as a facilitator of learning.

How does communication play an important role in your approach to teaching?

In 2018, I co-authored a paper on how teachers ask questions in class. My research on this project raised my own self-awareness about the types of questions I ask in the classroom. I found, through my own reflection, that, as with most of the subjects in our study, many of the questions I ask are either checks for understanding or simple calculations.

Since conducting this study, I have put considerable effort into asking more substantive and conceptually demanding questions of my students such as: “How can we apply the idea of the Riemann sum to find the volume of a solid of revolution?” This type of question places more responsibility on the students to think through what they have learned and to contribute mathematical content to the class.

You also became more mindful of the amount of time you wait after asking a question. Why?

Our study found that many instructors wait only a couple seconds after posing a question before answering it themselves. This does not leave students with enough time to think through a concept or problem. Though the silence can be uncomfortable at first, waiting just five or ten seconds longer increases the likelihood of student participation. Over time, this approach has turned my lectures into conversations.

Why did you make the first-year calculus sequence (MATH 121, MATH 122, MATH 200) textbook independent?

During a discussion with the math department heads it was brought up that textbooks are very expensive, don’t change over time and that we know how to teach better as time passes. The pandemic lockdown provided a unique opportunity to generate online content, such as lecture videos and online assessments for these courses. We ended up writing a whole library of problems. Jason Aran, associate department head of the math department, developed a lot of the materials and I built a website to provide a centralized location to house the content and practice problems for the four quarters of calculus. Over time, I have continued to improve upon the content, adding a bit more each year and compiling all of my written materials into an online textbook that I make available to our students.

Did you ever get to tell Mrs. Crosby the impact she had on you?

I did. A couple of years ago, I was at my old high school and asked if Mrs. Crosby was still there. We ended up going out to lunch and I was able to share how much she influenced me. She told me that when she first started teaching AP calculus, she would often wake up at 3 a.m. thinking of another way to teach a problem and working through it before she came to class that morning. She worked twice as hard as anyone else. Intuitively, that came across to us in the class. She didn’t put herself above us. In retrospect, and after I became knowledgeable about the best approaches for teaching, she did 100% of all the right things. It reinforced my own intuition.