Students Create Mock Livers, Kidneys Used for Training Across the World

By Natalie Kostelni

The summer heading into her junior year, Madison Titlow was at a crossroads.

A biomedical engineering major, Titlow didn’t have a minor, wasn’t interested in pursuing a master’s degree but knew she wanted to delve into something that took her out of her comfort zone.

She reached out to Steven Kurtz, PhD, director of Drexel’s Implant Research Center at the School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems, to see if any opportunities were available.

“I had never stepped off the path I was on and was very intimidated because I didn’t have any experience, but he was so welcoming,” Titlow said.

She was put to work on a project with Abigail Tetteh, a PhD student, first to make replicas of livers, and then kidneys, using 3D printers at the Implant Research Center. The replicas are used to train surgeons and other health care providers on how to preserve these complex organs prior to transplantation.

Titlow and Tetteh’s work was part of a project with multiple partners including Bridge to Life Ltd., an Illinois company that makes organ transplant medical devices; Philadelphia-based Gift of Life Donor Program; and David Reich MD, an internationally recognized leader in organ transplant surgery who was chief of transplantation at Drexel’s College of Medicine, is now at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Florida, and also remains Professor of Surgery and of Biomedical Engineering at Drexel.

In addition to its research impacts, the project also had a significant impact on the students’ educational experience. For Titlow, it led to a career path — a co-op and then job after graduating in June 2023. For Tetteh, it helped secure a year-long fellowship with the FDA.

Mock Organs for Training

Bridge to Life makes products that promote organ preservation and organ perfusion technologies for transplants. Organ perfusion involves maintaining the viability of an organ between the time it is removed from a donor and transplanted.

Reich has been primary investigator overseeing a multicenter clinical trial that evaluates and compares the safety and efficacy of using static cold storage, which is the current standard for organ preservation, against hypothermic oxygenated perfusion, or HOPE, using Bridge to Life’s VitaSmart Liver Machine Perfusion System. Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion is a method of preserving an organ by continuously pumping an oxygenated solution into the donor organ.

The HOPE trial has been a success. Reich presented positive interim trial results in the summer of 2023 at the American Transplant Congress that indicated the process was transformative and the HOPE process was “statistically superior,” according to a company news release.

Bridge to Life needed to train surgeons and other health professionals at the trial sites on how to use the machine to preserve organs, and now, with the clinical trial demonstrating that the VitaSmart Liver Machine Perfusion System is better than storing a liver in a container of ice prior to transplantation, it is anticipated that more hospitals and surgeons will require training.

“What isn’t easy to do is get ahold of a human or animal organ to train with,” said Chriss Stanford, director of clinical affairs at Bridge to Life.

That’s why Reich turned to Ken Barbee, senior associate dean at the School of Biomedical Engineering at Drexel. “When David told me what they were looking for, I was sure it was something the students could do,” Barbee said.

Through a sponsored research agreement with Bridge to Life, Barbee organized a project in which students, including Titlow and Tettah, used 3D printers to manufacture livers the company could use to teach surgeons and enable them to practice using the medical device. The students needed to design a liver that resembled the real thing, taking into account a myriad of variables such as color, shape, weight, density, surface texture, feel and tubing in and out of the organ to replicate vessels.

“They didn’t need to be as perfect as a liver, but they needed to be realistic,” Barbee said.

With some tweaks along the way, students such as Tettah and Titlow went to work producing 40 livers for Bridge to Life. Each organ is stamped with a Drexel logo and used at conferences and training programs around the world.

Kidneys are next. Bridge to Life contracted with Drexel to design a 3D kidney, which requires different design dimensions than a liver, to use in training. As part of their research to gain a better understanding of kidneys, students visited Gift of Life to get a first-hand view and feel for the organ to inform their design. The students are expected to initially produce 60 kidneys.

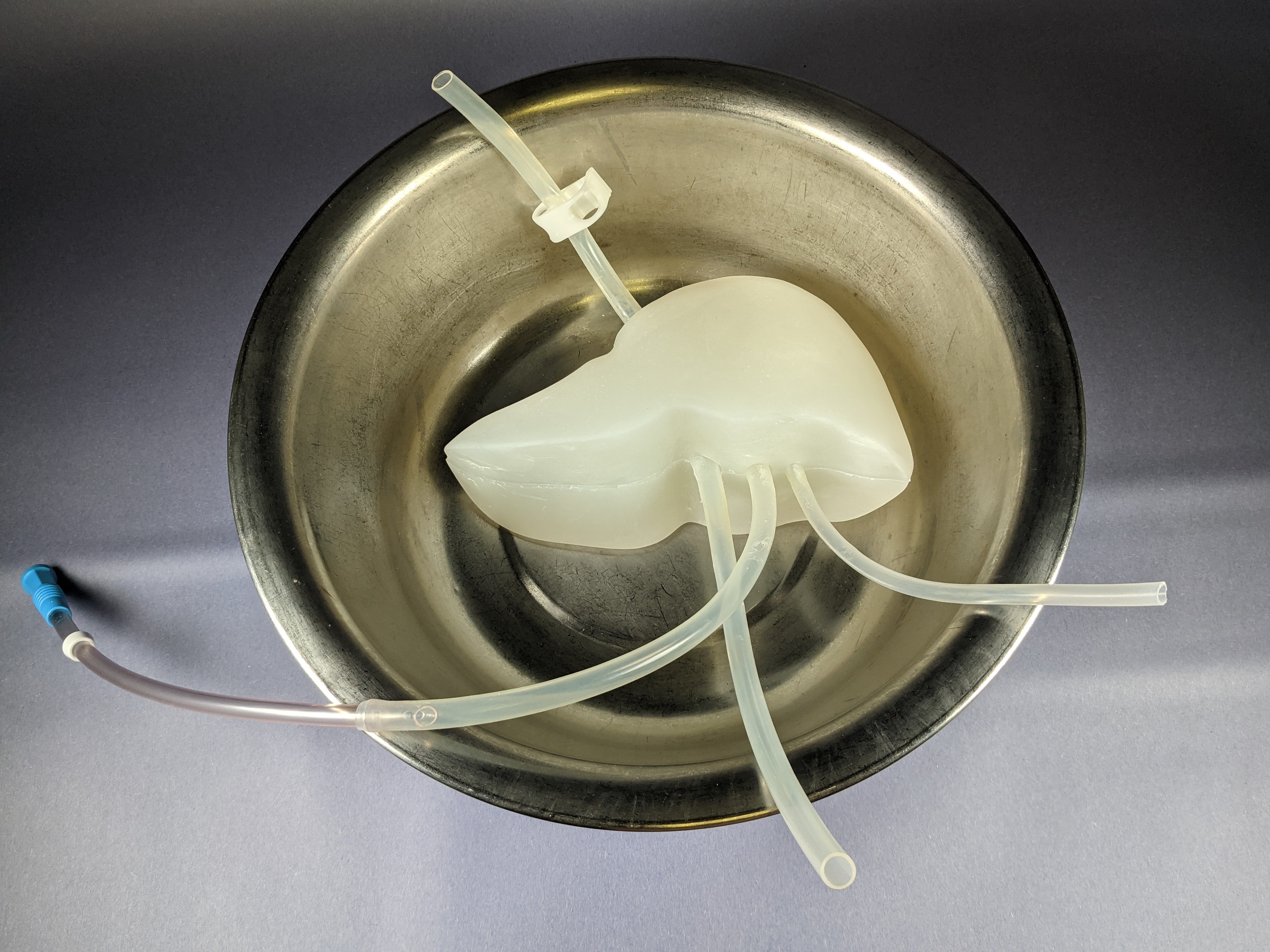

A work in progress prototype of the liver model. Photo Credit: Abigail Tettah

Project Leads to Job, Fellowship

While creating and using physical models in training isn’t new, the project with Bridge to Life has been rewarding.

“It’s been a fantastic learning experience for the students,” Barbee said.

For Titlow, the project helped her first land a co-op position with W. L. Gore & Co. and later a full-time position at the company’s medical products division in Flagstaff, Ariz.

“Drexel and those at the Research Implant Center gave me the materials I needed and space to succeed and fail, and because of that, I gained a lot from this project,” Titlow said. “The technical skills were a huge interest during my job interview, and they are definitely transferrable to a lot of other spaces.”

Titlow moved to Flagstaff at the beginning of September to start her new job.

Tetteh is a biomedical engineer pursuing a doctorate at Drexel and focuses her research on medical implants and devices. The work on the mock organs helped her earn a fellowship with the FDA that concluded in September.

“The whole experience was great,” Tetteh said. “It is something I knew was going to be used in real life to help surgeons and junior surgeons. It’s nice to know you are helping those on the frontline, and it is also tied to my research.”

This project advances education and research in pursuit of biomedical innovation, Reich said. In the end, it was that combination that benefited all of the parties involved. “It is gratifying to collaborate with the students and Dr. Barbee,” he said. “I'm thrilled that the multicenter trial of hypothermic oxygenated perfusion is showing significant benefits for liver transplant recipients - a trial that the students contributed to by designing these organ models for device training.”