‘The Drexel Jinx’ Broken Only by Isaac Asimov

This article is part of the DrexelNow “Faces of Drexel” series honoring Drexel’s history as part of the University-wide celebration of the 125th anniversary of Drexel’s founding in 1891.

For a short period during Drexel University’s 125-year history, every commencement speaker was jinxed. It sounds farfetched — as all jinxes, curses and superstitions inevitably do — but the facts don’t lie.

And here’s the truth: from 1972 to 1975, every speaker who addressed Drexel’s commencement left their jobs (involuntarily, for the most part) about half a year later. What’s more: half of the speakers died less than five years after addressing Drexel Dragons. And no one, it seemed, was immune to the so-called “Drexel Jinx” — not even the vice president of the United States.

It all began after Brig. Gen. George Lincoln, head of the Office of Emergency Preparedness, spoke at the 1972 commencement. He was out of a job when the office was abolished in January 1973 — a little more than half a year after he spoke to Drexel Dragons at graduation — and died two years later in 1975.

Seems normal, right? Just a coincidence. Not a big deal. Nothing to worry about…

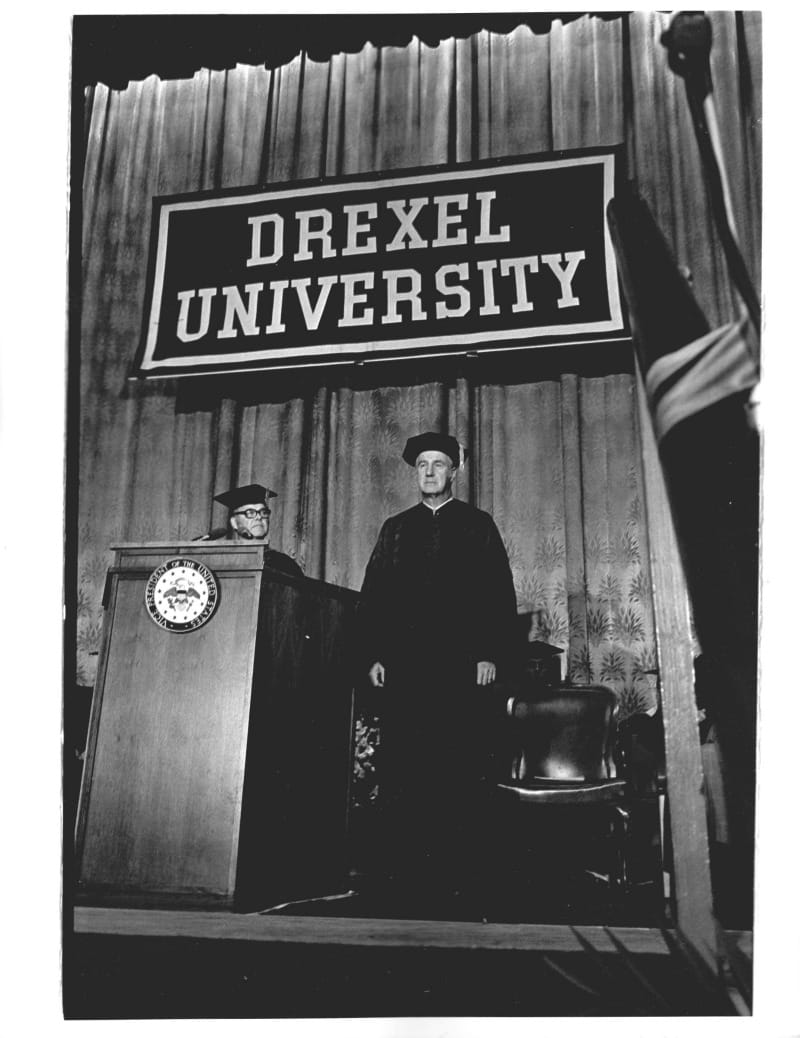

The next speaker was forced to resign from his position so famously (or infamously) that it was harder to ignore the coincidence. The second victim of “The Drexel Jinx” was Vice President Spiro Agnew, who resigned in disgrace and pleaded no contest to criminal charges of tax evasion in October 1973, just a few months after addressing Drexel graduates.

The jinx’s parameters shifted a little for the 1974 speaker, Sen. Sam J. Ervin, Jr., D-NC. He was out of a job less than six months after visiting Drexel, which was par for the course — but that’s because he retired just before his term ended in December 1974. During a Senate career lasting 20 years, Ervin fought and helped take down the Jim Crow laws, Sen. Joseph McCarthy and President Richard Nixon, the latter through his position as chair of the Senate Watergate Committee. But six months after speaking at Drexel, he retired.

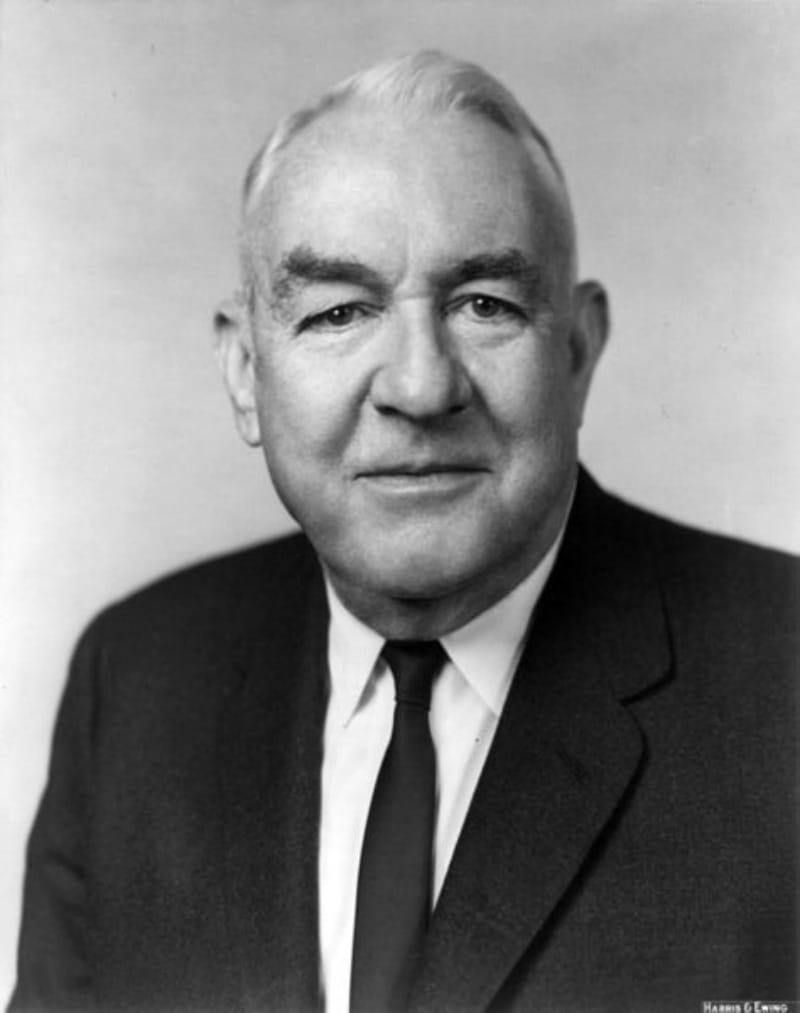

If University officials were aware of “The Drexel Jinx” by this point, it seems as though they didn’t believe in it. Yet another high-profile government official was chosen for the position as commencement speaker — and left his job less than six months later. The last victim was Secretary of Commerce Rogers Morton, who was replaced shortly after President Gerald Ford’s “Halloween Massacre” in November 1975. His fallout from “The Drexel Jinx” wasn’t as severe as other victims: he was named counsel to the president a few weeks later and became Ford’s campaign manager in the 1976 election, which he lost. Morton died of cancer in 1979, four years after speaking at Drexel.

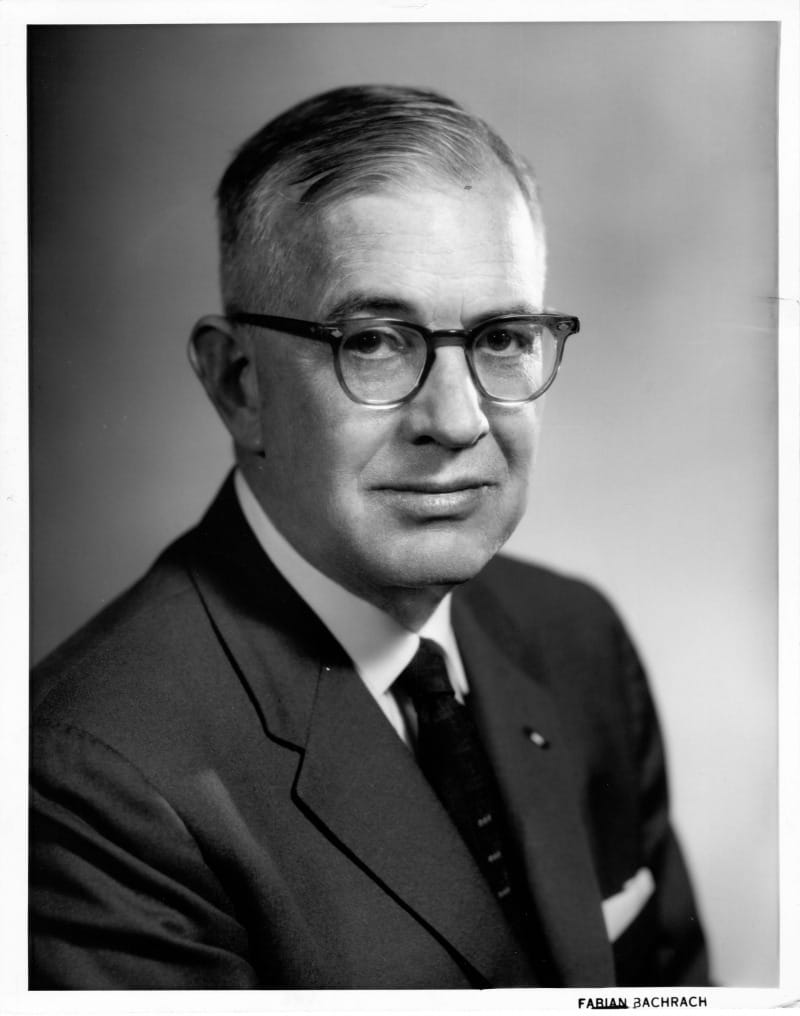

By 1976, the jinx was too powerful to ignore, and the University administration decided to do something about it. After four years of bringing notable politicians and government officials to campus and seeing them leave their position soon afterward, the University came to an obvious conclusion: no more politicians and government officials. Drexel President William W. Hagerty suggested that the Honors and Awards Committee of the Board of Trustees consider the recommendations of the graduating seniors as well as the faculty’s Public Observances Committee — but only on the condition that the speaker had to have an academic background.

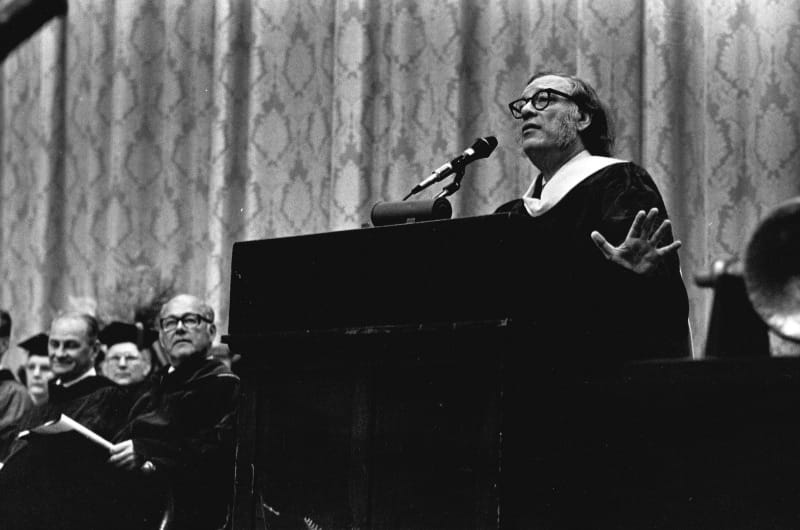

The seniors chose prolific science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov, PhD, who technically fit the requirement: throughout his long-established writing career, he had retained an associate professorship of biochemistry at Boston University, even though he had stopped regularly teaching in 1958. Suffice to say, he probably wasn’t the type of academic that the administration had been expecting.

“Believe it or Not: Seniors Get Their Wish,” announced the front-page, above-the-fold headline in the March 9, 1976, issue of The Triangle. The story expanded on the ultimate “get,” reporting that “while more responsibility by the seniors might have been an aid in bringing Asimov to Drexel, ‘The Drexel Jinx’ was probably the more determining factor in the decision.”

It’s unknown if Asimov was aware of the jinx when considering the proposal, but he nonetheless accepted the offer to speak at the University’s commencement at the Philadelphia Civic Center at Convention Hall on May 29, 1976.

“It is only by continuing to learn that you remember what you have learned,” Asimov told the graduates, according to that year’s Lexerd yearbook. “It is only by never stopping your education that you can be educated at all. I ask you to remember that.”

Asimov, described in the commencement program as a “scientist, science educator, futurist and engineer of the bridge of understanding which spans the scientific and humanistic cultures,” was also awarded a Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa. There was no mention of his writing career or achievements in the biography that Drexel published, even though Asimov had published his 173rd book that month and even included that fact in the autobiographical summary he submitted to the University (held now in University Archives) as a resource for writing the commencement program biography.

Even with that slight, the commencement ceremony seemed to go off without a hitch. Asimov came, he spoke, he left and went on with his life. Summer turned into fall, which turned into winter, and Asimov still retained his professorship, gave lectures and wrote articles, stories and books. Then there was a new commencement speaker addressing a new graduating class — the class of 1977, or students who had entered the University in the first academic year in which the jinx started. Time went on, and it seemed as though “The Drexel Jinx” was seemingly broken — by one of the world’s greatest science-fiction writers, no less.

As further confirmation that “The Drexel Jinx” was no more, Asimov was promoted to professor in 1979, still without regularly teaching or receiving a salary. Years became decades — four of them, to be exact — and there hasn’t been a “Drexel Jinx” occurrence since 1975.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s gone for good.

In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.