Male Hepatitis B Patients Suffer Worse Liver Ailments, Regardless of Lifestyle

By Frank Otto

By Frank Otto

- Children Exposed to Antiseizure Meds During Pregnancy Face Neurodevelopmental Risks, Drexel Study Finds

- Standardized Autism Screening During Pediatric Well Visits Identified More, Younger Children with High Likelihood for Autism Diagnosis

- Reporting Into the Void: Research Suggests Companies Fall Short When It Comes to Addressing Phishing

- Drexel to Expand Its Community Technology Resources at the Dornsife Center With $1.5M Grant from PA Broadband Development Authority

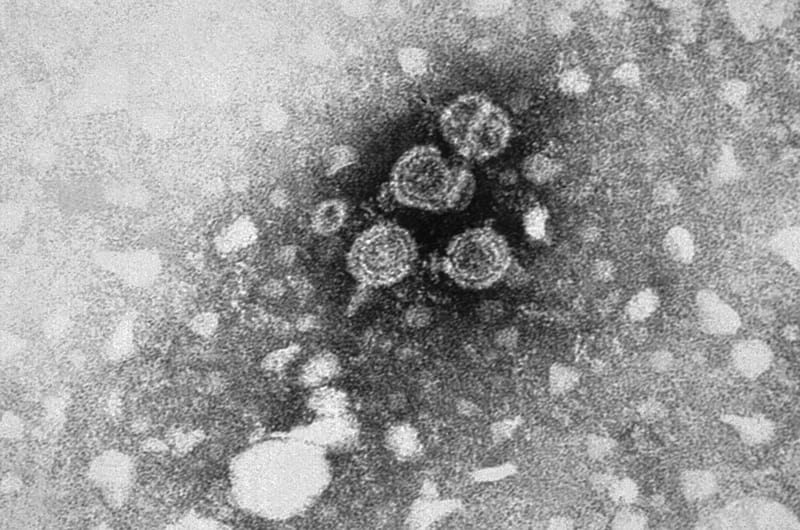

Why men with hepatitis B remain more than twice as likely to develop severe liver disease than women remains a mystery, even after a study led by a recent Drexel University graduate took lifestyle choices and environments into account.

In an attempt to explain the disparity between the two, suggestions have been made that lifestyle choices, such as drinking, smoking or even how much water a person drinks, might be the reason.

But Jing Sun, PhD, a post-doctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University and a graduate of Drexel’s Dornsife School of Public Health, found no such evidence in her recent study conducted with collaborator from the school. A patient’s sex remains the best indicator for liver disease severity.

“Currently, there is no therapy that can cure hepatitis B infection,” Sun explained. “People infected with it have very different clinical outcomes: Some remain without symptoms throughout their lifetimes while others develop severe liver conditions, such as liver cancer, cirrhosis and live failure. Predicting those who will eventually develop liver disease provides important information for intervention strategies.”

If it had turned out that lifestyle choices and a hepatitis B patient’s environment were stronger factors into the condition of their liver than sex, that would have been relatively good news, since both lifestyle and environment can be changed.

But still, the study found that men with hepatitis B were just over twice as likely to develop severe liver disease as women.

“Previous studies suggested males were two to four times more likely to develop liver cancer than females,” Sun said. “In our study, we observed males were 2.08 times as likely. The magnitude of effect is within the range we would expect, then.”

Published in PLOS-One, Sun’s paper used data from the Haimen City cohort, which was established in eastern China, of hepatitis B patients. Dating from 2003, the data included information about how often 1,863 men and women drank alcohol, smoked, and drank water and tea. It also used information from physical examinations, ultrasounds, and blood tests to determine liver disease condition, ranking from “normal” to “severe,” which included cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Drinking alcohol was significantly tied to liver disease risk, and the study found that there was a difference between men and women there, too. Men who are current drinkers had eight times the risk of developing liver disease and women who currently drink were four times as likely.

Smoking was also found to increase risk for both men and women: men who smoked were more than twice as likely to develop liver disease and women were 6 percent more likely.

But the study found that even when accounting for these different factors, sex was still a strong, independent indicator of liver disease risk in the hepatitis B patients. Men consistently were two times as likely as women to develop cirrhosis or live cancer.

So why is sex such a strong factor? What makes males and females so different in their risk?

“Based on the results of animal studies done by other groups, we hypothesize such differences are due to other biological causes (e.g. sex hormones),” Sun said.

And while lifestyle or environmental risks for patients don’t seem to explain the difference in live disease in men and women who have hepatitis B, those factors aren’t meaningless, either.

“Of course, even though the lifestyle difference between males and females cannot explain the gender difference, patients infected with hepatitis B should still avoid these risk factors to prevent liver disease progression,” Sun concluded.

The paper, “No contribution of lifestyle and environmental exposures to gender discrepancy of liver disease severity in chronic hepatitis B infection: Observations from the Haimen City cohort” — which Sun co-authored with Lucy Robinson, PhD, Nora Lee, PhD, Seth Welles, PhD, ScD, and Alison Evans, ScD, all of the Dornsife School of Health — is available here.

In This Article

Contact

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.