The Drexel President Who Edited F. Scott Fitzgerald

This article is part of the DrexelNow “Faces of Drexel” series honoring Drexel’s history as part of the Universitywide celebration of the 125th anniversary of Drexel’s founding in 1891.

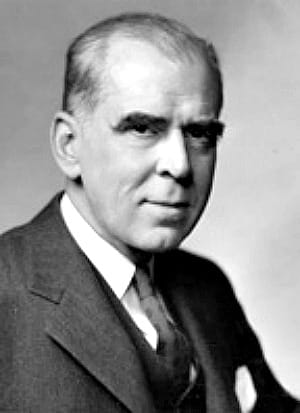

The new film Genius tells the story of famed editor Max Perkins, who famously started F. Scott Fitzgerald’s career. But before that, someone else — someone who later became famous in his own right at Drexel — had edited and published Fitzgerald first: Drexel Institute of Technology President James Creese.

Creese, who presided over Drexel from 1945 to 1963, attended Princeton University alongside Fitzgerald from 1914–1918. He was the managing editor of Princeton’s literary magazine as well as co-editor of an anthology of pieces written by Princeton alums. As it turns out, he edited Fitzgerald’s work for both publications.

The two men ran in similar literary circles on campus. Both students were members of the English Department and studied humanities and poetry for their Bachelor of Letters degrees. Creese and Fitzgerald also joined Whig Hall, an exclusive literary, philosophical and debate club whose alumni included founder James Madison and Woodrow Wilson. The organization published Princeton’s Nassau Literary Magazine, also called The Nassau Lit. During their time on campus, the publication made what Fitzgerald later described as “a sudden successful bid for attention” by increasing the scope and quality of its work. Unsurprisingly, both men were frequent contributors.

The student newspaper, The Daily Princetonian, often reviewed the Nassau Lit. A June 1916 article described Creese’s poem “A Ballad of Sir Richard Steele” as “whimsical and charming verse,” whereas Fitzgerald’s parody of John Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” titled “To My Unused Greek Book,” was deemed “amusing, but marred inexcusably by carelessness.” A May 1918 review praised Creese’s story “Property Qualifications” for its “excellent comedy, and delightfully easy narrative style,” while identifying Fitzgerald’s poem “City Dusk” as having “a characteristically clever, but indeterminable and invertebrate, set of stanzas.”

Ultimately, the two men took different paths: Creese graduated in 1918 and Fitzgerald dropped out in 1917. But the parallels in their lives didn’t stop there. In fact, both men continued to write about Princeton (and its various publications).

After serving in World War I, Creese returned to Princeton to earn a Master of Arts degree in English in 1921. While on campus, he co-edited “A Book of Princeton Verse II: 1919,” which featured poetry and literature written by Princeton students. Creese was the youngest alum and co-editor involved with the project. He helped select and approve pieces, including seven poems of his own. Three of Fitzgerald’s poems that were published in the Nassau Lit were included in the second volume: “Marching Streets,” “The Pope at Confession” and “My First Love.” It was the first time he'd ever been published in a book.

The preceding collection, “A Book of Princeton Verse I: 1916,” featured work from Creese but not Fitzgerald. Both books were later compiled into “A Book of Princeton Verse, 1916–1919.” Fitzgerald kept the second volume and the cumulative anthology (both of which he annotated) for the rest of his life; they are now part of his personal library of over 300 books held in the Princeton University Library.

A year after “A Book of Princeton Verse II” came out, Fitzgerald famously wrote about Princeton — and its literary magazine — in his debut best-selling novel “This Side of Paradise” (1920). He established himself as the preeminent writer of what he dubbed the “Jazz Age,” or post-WWI America. Still, Fitzgerald recycled Nassau Lit pieces for later publication in magazines as well as his short story collections “Flappers and Philosophers” (1921) and “Tales of the Jazz Age” (1922). Most of his undergraduate work was collected into posthumous anthologies.

In his lifetime, Fitzgerald published three more completed novels, including the now-classic “The Great Gatsby,” but none had the immediate success as his debut. In fact, 44-year-old Fitzgerald considered himself a failure when he died of a heart attack (while reading the Princeton Alumni Weekly) in 1940.

Creese continued to write throughout the rest of his life, though not as prolifically as Fitzgerald. He published articles, books and essays while leading higher education institutions at the Stevens Institute of Technology and later at Drexel. His 1949 address “A.J. Drexel, 1826—1893, and his Industrial University” was published as a book and can be found in Drexel’s W.W. Hagerty Library.

In 1961, five years before he also died of a heart attack, Creese wrote the forward to the inaugural issue of Drexel’s new literary magazine, The Gargoyle (the predecessor to its current publication Maya). The 65-year-old offered writing advice and reminisced about his own experiences at the Nassau more than four decades earlier.

“Looking back, I am impressed by the number of able and later distinguished authors who were among us in college,” he wrote.

Creese went on to identify those prominent alums, of which there were many. Of course, he included Fitzgerald, whose name and legacy had been restored by that time. Creese honored his former colleague’s legacy and career by describing him as “a novelist from whom an era in American fiction has taken its name.”

In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.