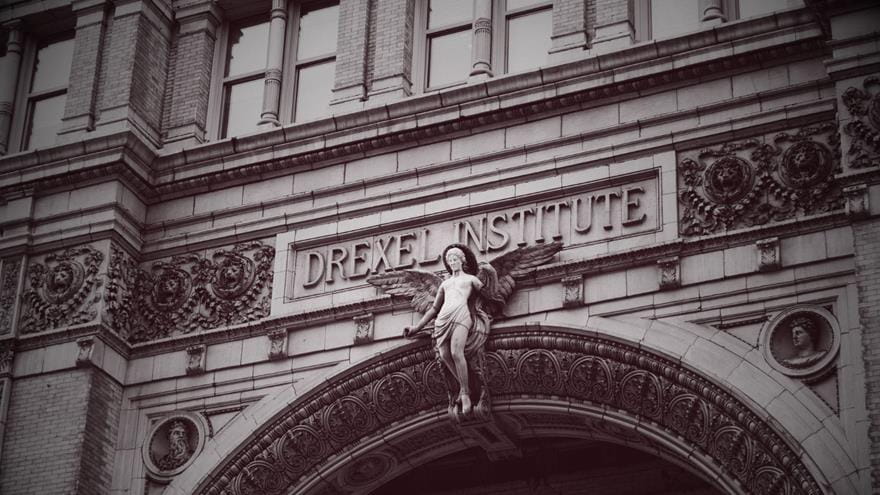

How Did Drexel Celebrate its Other Anniversaries?

This article is part of the DrexelNow “Faces of Drexel” series honoring Drexel’s history as part of the University-wide celebration of the 125th anniversary of Drexel’s founding in 1891.

To celebrate Drexel’s 125th anniversary, the University has created a time capsule, a short historical video, a free public lecture series, a beer, a book and a University-wide celebration. And that’s just been in the past fall term.

DrexelNow takes a look back at the University through the ages to measure how different the celebrations have been over the years.

Drexel at 100 — 1991

Just like for its 125th, Drexel also put out a special anniversary video and book for its centennial. The book, “Drexel University: A Century of Growth and Challenge,” used photos taken by photojournalist Chris Usher during one year on campus to complement archival photos and historical text. A lecture series was also held as requested by Drexel’s President Richard Breslin.

Special only to the Drexel centennial was the University’s attempt to build the world’s largest ice cream sandwich — which then became the world’s largest ice cream sandwich food fight.

A special jam and carnival was held in May 1991 that The Triangle said “may have been the best centennial event of the entire year” A “Taste of Philly in the Quad” night and a special “Centennial Ball & Late Night Dance Party” held at the Franklin Institute that was themed around Drexel’s first decade in the 1890s.

For Founder’s Day, Dragons engaged in a hokey-pokey dance party — yes, really — in the Main Building for a segment on Good Morning America. All participants received a free bottle of Pepsi.

For both 1991 and 1992 commencements, graduating students received special degrees with “Centennial 1891–1991” under the seal. The keynote speakers were NASA astronaut Guion Bluford, the first African American in space, and John Sculley, then-CEO of Apple Inc., respectively.

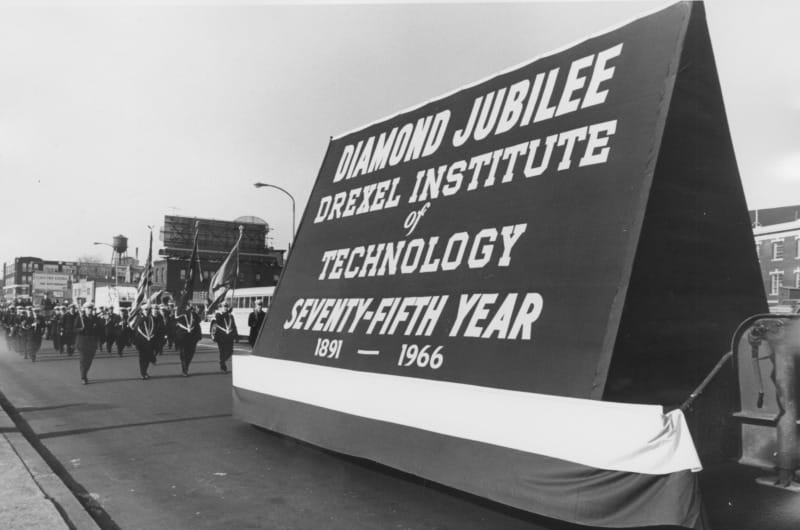

Drexel at 75 — 1966

Philadelphia’s 30th Street post office celebrated Drexel’s anniversary from Nov. 1 through Christmas by cancelling 30,000 pieces of first-class mail per hour with a special three-line inscription:

Drexel Institute of Technology

1891 – 1966

75th Anniversary

An afternoon parade from campus to City Hall and a Founder’s Day ball at night on Dec. 6 was planned, but many students complained that in order for them to participate, they would need half a day to catch up on their studies (it was the week before finals). Classes were cancelled from noon on Dec. 6, 1966 to noon on Dec. 7.

The ball, held at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, featured music from Duke Ellington and his orchestra. The Dean of Women complied with another popular demand and extended curfew at the women’s dormitory until 2 a.m.

In 1966, the Anthony J. Drexel statue was moved from Fairmount Park, its home for over half a century, to campus. The statue was originally placed near the 33rd Street trolley entrance — where the Pearlstein Business Learning Center currently stands — and can be found today outside of Gerri C. LeBow Hall.

Drexel at 50 — 1941

Drexel’s 50th anniversary started in the months before the United States’ involvement with World War Two, which meant that Drexel was hesitant to plan a year’s worth of activities, which was typically undertaken for later anniversaries.

A homecoming festival and football game in October welcomed alumni from as far back as the class of 1893 to celebrate their alma mater’s golden jubilee. Tea was served after the game at the Sarah Van Rensselaer dormitory.

The semi-centennial main celebrations took place on Founder’s Day, exactly 50 years (to the hour) after the Dec. 17, 1891 founding of the institution — and just 10 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The event took place during finals week — so all classes and finals were canceled from 11 a.m. on Dec. 17 to noon on Dec. 18. At the ceremony, male and female students modeled clothing representative of what Dragons would have worn during the 1890s, 1910s, 1920s and 1940s.

On Founder’s Day, Dragons held a traditional moment of silence for its founder, who was also honored that afternoon when a coalition of faculty, students and Drexel family members placed a wreath at the foot of his statue in Fairmount Park.

In 1942, two professors wrote a book on Drexel’s history (sound familiar?). “Drexel Institute of Technology, 1891–1941” was written by English professors Edward D. McDonald and Edward M. Hinton.

Dragons were shocked midway through the anniversary year when Drexel’s president, Parke R. Kolbe, who had been in poor health, died on March 1, 1941. Kolbe had been celebrating his own Drexel anniversary for his 10th year as president.

Drexel at 25 — 1916

For Drexel’s 25th anniversary, the institution did not celebrate as it would in the future.

The main celebration was Drexel’s convocation, which was held on Oct. 19 and 20, 1917, and featured a variety of leaders focusing on the mobilization of technology in America and on campus for World War I.

“To the casual view there appears all too little that is truly commemorative in the proceedings of the Institute’s twenty-fifth anniversary,” wrote McDonald and Hinton in “Drexel Institute of Technology, 1891–1941.”

But they agreed that President Hollis Godfrey’s decision to hold such a large event and thus raise Drexel’s profile as a leader in technological education during its 25th year shows that “if in retrospect the occasion seems unduly ceremonious, one senses in its design and direction a shrewd promotional brain.”

In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.