Growing inequality: Extreme heat as a driver of low birthweight across Latin American cities

Posted on

September 19, 2022

By: Octavio Alanis

SALURBAL Project

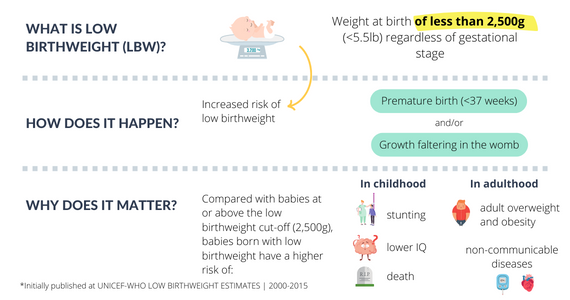

The effects of climate change, including increasingly frequent and prolonged extreme temperature events, are gaining attention as critical risks to human health. In their 6th Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (or IPCC) found that the countries of Central and South America, will continue to see increases in temperature, with heat waves increasing in frequency, intensity, and duration. Changes in ambient temperatures – the temperature of the surrounding environment – pose a major risk to pregnant women and developing fetuses and have been linked to birth defects and other pregnancy complications. Studies have shown that there is a link between temperature and low birthweight, but little research has focused on the impact in Latin America. Additionally, while some studies have shown that higher temperatures are associated with lower birthweight, others have shown an association with colder temperatures and lower birthweight. In order to address the lack of conclusive results, a SALURBAL study published in September 2022 in Environment International, examined the association between ambient temperature and term birthweight in Latin American cities in Brazil, Mexico, and Chile.

What do changes in ambient temperature mean for newborns’ health?

Birthweight can be attributed to a variety of factors such as maternal lifestyle, maternal care before, during and after birth and social support. It is an important determinant of child survival and development, as well as long-term consequences like the onset of non-communicable disease throughout life. Changes in ambient temperature may play a role in driving low birthweight. During pregnancy, heat is transferred to the fetus via the placenta and uterus, resulting in a 0.3° C to 0.5° C higher temperature than that of the mother’s body. Additionally, the increased demand on a woman's metabolic system and increased weight gain during pregnancy can affect a woman’s ability to regulate her body temperature, making her more vulnerable to hot temperatures, heat shocks, and dehydration. These processes can reduce the amount of amniotic fluid in the amniotic sac, placing the fetus at risk of malnutrition in the womb.

Term live births were defined as those within 38-41 weeks of gestation.

Ambient Temperatures and Birthweight in Latin America

SALURBAL researchers looked at data on term live births across 265 cities in Brazil, Mexico, and Chile and analyzed birthweight for about 15 million term births from 2010-2015.

Researchers found that in Brazil and Mexico, higher temperatures (relative to the reference of 19° C) during gestation are associated with lower birthweight. Moreover, these findings indicated that there is a stronger relationship during the third trimester of gestation.

The study did not show many significant findings for Chile, possibly because Chile is the coldest country of the three, but average estimates suggest that lower temperatures may be associated with lower birthweight.

What can we do?

To combat the negative effects of higher temperatures on newborn health, countries should invest in improvements in maternal education, prenatal care, and work to create more equitable socioeconomic conditions overall. Maternal education can act as an indicator of a mother’s socioeconomic position and can reflect her access to and use of prenatal care, diet during pregnancy and timing of fertility, all of which can impact birthweight. Prenatal care allows for caregivers to track mothers’ and their fetus’ status with each visit, and is a key factor in preventing low birthweight. On average, mothers in Chile benefit from better access to prenatal care as compared to mothers in Mexico and Brazil, which may explain the lack of findings from Chile in the recent study.

More research must be performed in Latin American regions regarding low birthweight and effective policies and programs for prevention. In order to bridge the gaps in knowledge in this region, SALURBAL’s MAPECA (Maternal, Infant, Child, and Adolescent Health) focuses on studying inequalities in maternal, child, and youth health in Latin American urban environments. The group works to disseminate their results to support decision-making for more equitable cities for all. The MAPECA group has published findings from their research on how the social environment, women’s empowerment, and urban areas can affect infant health outcomes.