Looking Up to the Geniuses Who Never Left Campus

- Drexel to Expand Teacher Residency Model in Philadelphia with Support From William Penn Foundation

- Josephine O. Ibironke, OD, Appointed Dean of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry

- Drexel’s College of Nursing and Health Professions Receives $1 Million for Scholarships from the Bedford Falls Foundation – DAF to Address Nursing Workforce Shortage

- Laura Turner to Join Drexel University as Senior Vice President for Institutional Advancement

This article is part of the DrexelNow “Faces of Drexel” series honoring Drexel’s history as part of the Universitywide celebration of the 125th anniversary of Drexel’s founding in 1891.

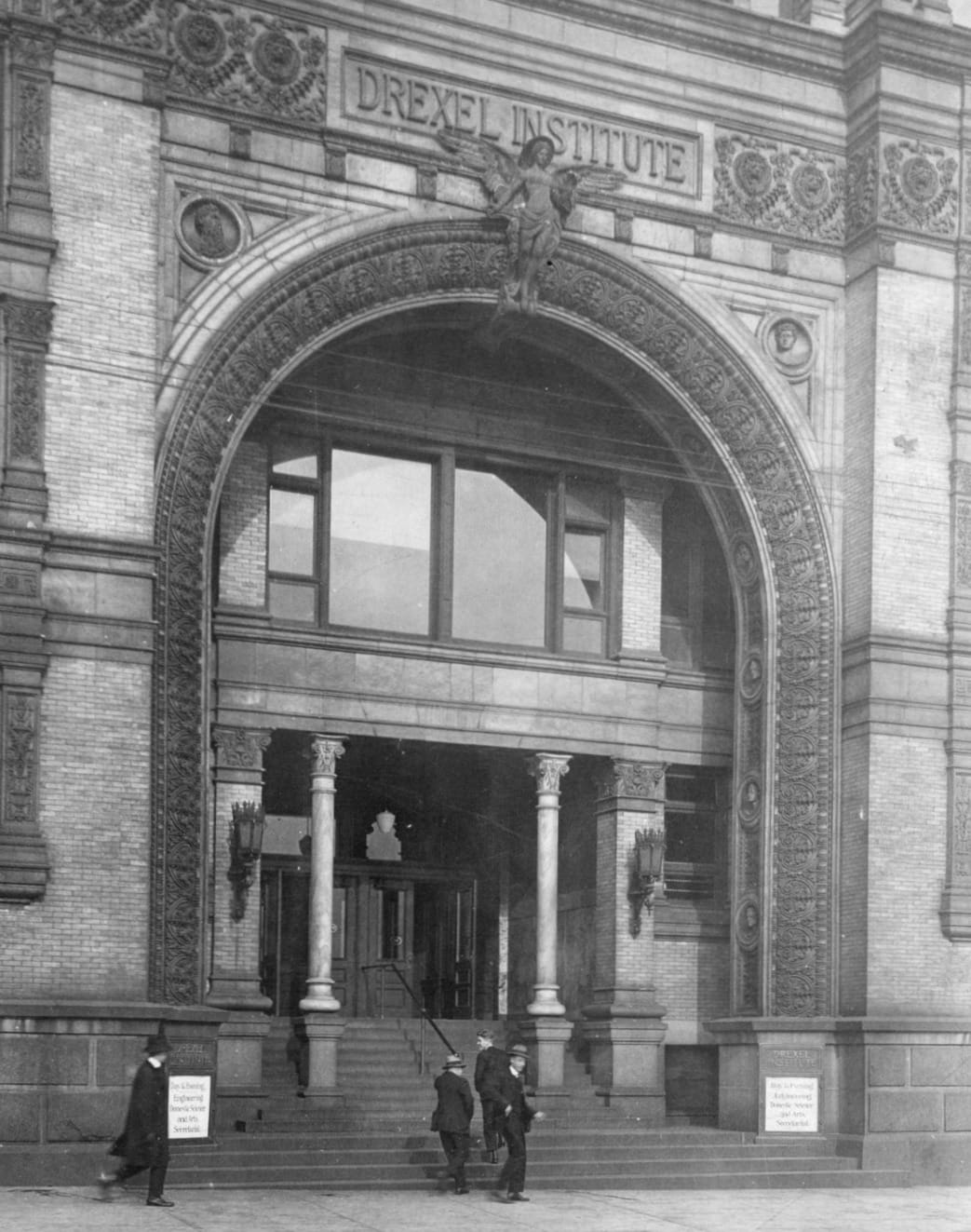

You’ve probably walked under the arch on Main Building’s Chestnut Street entranceway, but have you ever looked up and said “Hello” to Galileo? No? Well, then, have you ever nodded at William Shakespeare? Locked eyes with Christopher Columbus? Smiled at Thomas Jefferson?

Each one of these notable creators, discoverers and leaders in their various fields has been prominently featured on Drexel’s classic Italian Renaissance-style Main Building since it was completed in 1891. At the time, they were specifically chosen for rendering because of their contributions to the arts and sciences taught by the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry — which still remains true for the University today.

Galileo was chosen for representing astronomy; Shakespeare for drama; Columbus for navigation and Jefferson for government. The other luminaries depicted in the archway are Johann Sebastian Bach for representing music; Raphael for painting; Goethe for poetry; Sir Isaac Newton for mathematics; Daniel Faraday for physics; Alexander von Humboldt for natural history; Michael Angelo for sculpture and William of Sens, the medieval master-builder who designed the Canterbury Cathedral, for architecture.

In the middle of these mortal geniuses stands the Genius of Knowledge herself, a winged, nude figure situated in the center of the 35-foot-tall arch. She is featured in front of a tablet bearing the name of “Drexel Institute,” which has not been changed since Drexel transformed into a university in 1970. In the spandrels of the arch are medallions of Apollo and Moses, both looking to the Genius of Knowledge between them. It's no surprise, then, that this entranceway was sometimes called the "Great Portal."

The building — as well as that arch, the Genius of Knowledge and those 12 high-relief medallion portraits — was designed by noted Philadelphia practicing engineer-architect Joseph M. Wilson. Wilson, who was a co-founder of the prominent Victorian-era architecture and engineering firm Wilson Brothers & Company, had gained fame for creating the Main Building (another Main Building!) for Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition of 1876, as well as Reading Terminal and the Pennsylvania Railroad’s original Broad Street station. In the years prior to developing the hallmark of the future Drexel Institute, Wilson simultaneously served as the president of the Franklin Institute and the president of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Wilson had a special connection to University founder A.J. Drexel. The men first worked together when Wilson designed the Drexel & Co. Bank at Fifth and Chestnut streets in 1884 and added subsequent additions during that decade. The trust and partnership between the two was so great that Drexel even hired Wilson to design several houses for Drexel’s children in his family compound at 39th and Walnut streets. Later, Wilson built Randell Hall to the east of Main Building in 1901; it was one of the last projects he was involved with before dying in 1902.

It came as no surprise that Drexel chose Wilson to design the hallmark building of his new institute. But before that happened, Drexel arranged for Wilson to travel abroad in 1889 to view and learn about the new technical academies of Germany and England. This trip was financed on Drexel’s dime — or, more specifically, Drexel, Harjes and Co, which was the European branch of the Drexel Banking house — to prepare Wilson for this endeavor.

After three years of construction, Main Building was finished in 1891 and Wilson received great praise for his vision.

“Additional beauty is lent to the exterior by the ornamental terra-cotta work which is perhaps the most artistic ever applied to a building in this city,” read the dedication ceremonies booklet used in the December 17, 1891, formal ceremony announcing the opening of the Drexel Institute.

Main Building was certainly unique compared with its neighbor, the University of Pennsylvania. Unlike Penn and other universities at the time, Drexel’s campus didn’t feature the typical Gothic-designed buildings surrounded by green lawns and trees (a nod to colleges in English religious communities). Instead, Drexel was started on a single acre of an urban corner located two blocks away from a major commuter train station.

“The building’s design was different as well; its walls were of a bright buff brick and terra cotta with ornament derived from classical sources, though following no specific European prototype,” wrote George E. Thomas, PhD, an architectural historian who wrote “Drexel University: An Architectural History of the Main Building 1891–1991” as part of Drexel’s centennial celebration.

The exterior of Main Building has hardly changed in 125 years, though its surroundings certainly have. That means that generation after generation of Drexel students, faculty, staff and visitors have all walked under that archway on their way to classes or meetings — all under the supervision of some of the greatest contributors to humankind.

In This Article

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.