The Complete Dissection of a Human Cerebrospinal Nervous System (Known as “Harriet”)

Details and supporting documents

CONTENT WARNING: Some images currently on this page or added in the future may be disturbing to some readers.

NOTE: This page is a work in progress and will be updated with new information and/or questions.

The complete dissection of the human cerebrospinal nervous system known as “Harriet” was created by anatomist Dr. Rufus B. Weaver in 1888. At the time, this specimen was recognized as an important teaching tool in the field of neurology. The story of the specimen has been told with varying degrees of accuracy and at times without respect for informed consent or bodily autonomy. This page provides supporting documents for the history as we currently understand it.

The historical understanding is based on documents we have identified as of today. The way we understand history is shaped by what we know, what others know, what has been shared or published, and the time we live in. People uncover new historical details every day and we are confident that there is more to learn about the history of "Harriet" and Harriet Cole. We encourage researchers, the curious, and the concerned to contribute to this conversation.

This resource is an ongoing endeavor to provide educational information. It will be updated as new information arises or as new questions surface. Submit your anonymous questions here:

See also:

Supporting documents and resources for the interpretive labels used in the Complete Dissection of a Human Cerebrospinal Nervous System (Known as “Harriet”)

Interpretive label citations

The following sections are excerpts from the interpretive labels accompanying the nervous system dissection, with annotated citations and resources.

Introduction text

- In September 1888, after five months and over 900 hours of work, Dr. Rufus B. Weaver created the world's first complete dissection of a human cerebrospinal nervous system.

- By 1915, the dissection was recognized as an important teaching tool in the field of Neurology. Its likeness appeared in many textbooks, as well as in doctors' offices, classrooms, and laboratories across the country. Over the next century, throughout the medical world, the dissection became known as "Harriet."

- A.R. Thomas “A New Preparation of the Nervous System.” The Hahnemannian Monthly. 1889. (pg 65-68) - https://archive.org/details/hahnemannian24homo/page/n73/mode/2up

- “Prominent Homoeopaths II. Rufus B. Weaver, A.M., M.D.” The Hahnemannian Institute Vol. III., No. 2. Hahnemann Medical College. December 1895. (2 pages)

- “Prominent Physicians. No. 1. Rufus B. Weaver, A.M., M.D.” The Medical and Scientific News Vol. I, Number 1. December 1896 (2 pages)

- “An Anatomical Marvel That is Valued by Its Author at Ten Times Its Weight in Gold.” North American, July 1902.

- “Dr. Rufus B. Weaver.” Hom Monatsblatter. February 1907. (German)

- Note: List is not exhaustive.

Why is this dissection called "Harriet?"

- The dissection came to be called "Harriet" during Weaver's lifetime.

- Van Baun, William Weed. The Golden Jubilee of Rufus Benjamin Weaver. The Jubilee Address...and Dr. Weaver’s Reply.” The Hahnemannian Monthly. June 3, 1915. Drexel University College of Medicine Legacy Center.

- This article mentions Weaver’s dissection achievements and includes information on the cadaver: "Harriet Cole was a poor, ignorant negro woman, age 36 years, with no superfluous flesh or fat. Anatomically perfect. She had greatness and world-renowned forced upon her after death, by yielding up her entire Cerebro-Spinal Nervous System under the deft touch of the World’s greatest Anatomist. “Harriet” was not the inspiration of a moment, or an hour, or a day…On his return...and with “Harriet” floating idly in the vat.”

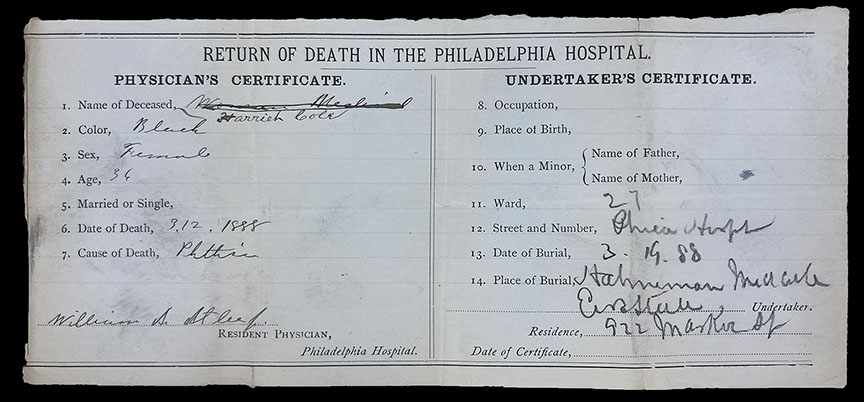

- There is evidence reflected in a March 1888 death certificate suggesting that the dissection was named after Harriet Cole, a woman whose unclaimed body was delivered to Hahnemann Medical College.

- Death certificate for Harriet Cole, “Health Death Returns: 03/10/1888 - 03/24/1888,” Department of Health; Board of Health; Bureau of Health: Death Certificates (RG 76.22), box A-6115. Philadelphia City Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The death certificate of Harriet Cole. Issued by Philadelphia General Hospital, 1888. Philadelphia City Archives.

Who was Harriet Cole?

- A Black woman named Harriet Cole lived in Philly in the 1880s. Records show she was born in Pennsylvania, worked as a domestic worker, and was unmarried.

- Harriet Cole was a patient at Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH), where she died from phthisis (tuberculosis) on March 12, 1888, according to the death certificate. Her age at the time of death was between 25 and 36 years old.

- Death certificate for Harriet Cole, “Health Death Returns: 03/10/1888 - 03/24/1888,” Department of Health; Board of Health; Bureau of Health: Death Certificates (RG 76.22), box A-6115. Philadelphia City Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

How did Dr. Weaver acquire the body of Harriet Cole? Did Harriet Cole donate her body to Dr. Weaver?

- At the time of Harriet Cole's death in 1888, laws set forth by the Pennsylvania State Anatomical Board and the Anatomy Act of 1883 governed unclaimed human remains. In accordance with these laws, unclaimed persons at PGH were transferred to area schools for "the advancement of medical science."

- UNCLAIMED CADAVERS, DISTRIBUTION AND DISPOSITION Act of Jun. 13, 1883, P.L. 119, No. 106 Cl. 35 § (1883). https://bit.ly/3S2MXgB

Additional questions related to the history of the Complete Dissection of a Human Cerebrospinal Nervous System (Known as “Harriet”)

Where is the "Harriet" exhibit today?

The exhibit is part of a broader exhibit on historical anatomical preparations located on the Queen Lane campus on the lower level of the Student Activities Center. This location was chosen as a visible location for sharing the medical school's history.

What are the effects of tuberculosis?

According to the CDC, “The general symptoms of TB disease include feelings of sickness or weakness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats. The symptoms of TB disease of the lungs also include coughing, chest pain, and coughing up blood.

What is the difference between a public hospital and a typical hospital? What kind of patients did PGH have?

In the United States, a public hospital is a hospital that is fully funded by the government and operates solely using the money that is collected from taxpayers to support healthcare initiatives.

In 1902, the Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). Along with city employees and other special cases, PGH only admitted medically disadvantaged patients who could not pay for their care.

- Lisa Levenstein, A Movement without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 161.

Who was Dr. Rufus Weaver?

Dr. Rufus Weaver was born in 1841 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He earned his medical degree from Pennsylvania Medical College in 1865. He continued his education with courses on anatomy and clinical medicine at University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College. He became demonstrator of Anatomy at Hahnemann Medical College in 1869 and was assigned the lectureship in surgical anatomy in 1878. He died in 1936.

Do donation records for Harriet Cole exist?

Through extensive searches over several years, Legacy Center staff have not uncovered any archival school or hospital records indicating that Harriet Cole knew Dr. Weaver or that Cole voluntarily donated her body to the Hahnemann Medical College. Harriet Cole's body was transferred to Hahnemann Medical College from Philadelphia General Hospital in 1888. This was a time when states were putting laws in place to curtail grave-robbing and other illegal methods of body procurement. It was also an era when voluntary body donations were extremely uncommon and poorly documented when they did occur. Many states, including Pennsylvania, legislated that unclaimed bodies of people who died in hospitals, asylums, and prisons would be allocated to state medical schools for the purpose of anatomical dissection. This alleviated the need for body snatching, but it strengthened the connection between medical school dissection subjects and people in poverty.