The Struggle

As women sought medical education in the mid-19th century, few medical schools were open to them, clinical educational opportunities were few, and career options were limited. Professional acceptance came slowly, in fits and starts, but incrementally the medical educational and professional landscape changed. What is seen as probably the first major barrier broken was Elizabeth Blackwell’s acceptance into Geneva Medical College in 1847.

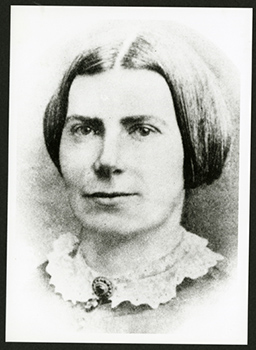

Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D., undated

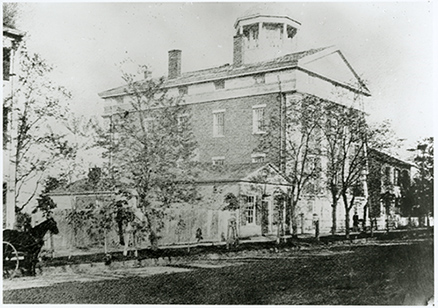

Geneva Medical College, circa 1848

In 1847, a school teacher named Elizabeth Blackwell decided to follow up on her interest in medicine and pursue a career as a physician. She applied to many of the east coast medical schools, but was ultimately rejected by all, except for Geneva Medical College. The faculty at Geneva did not want to decide on Blackwell’s admittance so they abdicated their responsibility and turned it over to the all-male student body. As a lark, the students voted to accept her, and in doing so, changed the history of medicine.

In 1856, Dr. Blackwell joined efforts with two other pioneering women physicians–her sister Emily Blackwell, who graduated from medical school at the Western Reserve College in Cleveland, and Marie Zakrzewska, a Prussian immigrant who graduated from Cleveland Medical School–to open the New York Infirmary for Women and Children.

Later, Dr. Blackwell moved to England, where she became the first woman to be licensed to practice medicine in London.

Mary Elizabeth Bates, M.D.

The most famous hazing incident in women’s medical education was perpetrated against one of AMWA’s founders, Mary Elizabeth Bates. In 1881, she became the first woman intern at Cook County Hospital and the target of a midnight raid found her in the operating room but still in bed.

Dr. Bates, a charter member of AMWA, remembered experiences she had as an intern at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. She was accepted as the first woman intern in 1881, after facing high standards, limited positions, and a rigorous oral examination. During her tenure, she was hazed by male interns who invaded her room during the night and dragged her—on her mattress—to an operating room to be entered as an “interesting case.” The story takes on legendary status as it has been retold over the years.

In Berth Van Hoosen’s 1926 retelling, she refers to the perpetrators as “real cave men” and that they had to work through the night to prevent the newspapers from reporting the story the next morning. Van Hoosen also writes of a supper being served in the operating room for the “bandits.” In Esther Pohl Lovejoy’s 1955 retelling, Intern Bates was taken from her room on a stretcher in “curl papers and all” to the operating room where the interns and nurses had prepared a feast in her honor. In a 1948 article based on an interview with an 87-year-old Bates, she relays that she was carried on her mattress and the banquet was already in progress.

For most of her years, Bates practiced in Denver, Colorado. She was active in the woman’s suffrage movement among other social causes. Several times she spoke before the Colorado state legislature several times on behalf of her causes. She made a great deal of money through an oil investment in Texas. After she retired, she volunteered with a couple of Denver area humane societies.

Back to Top