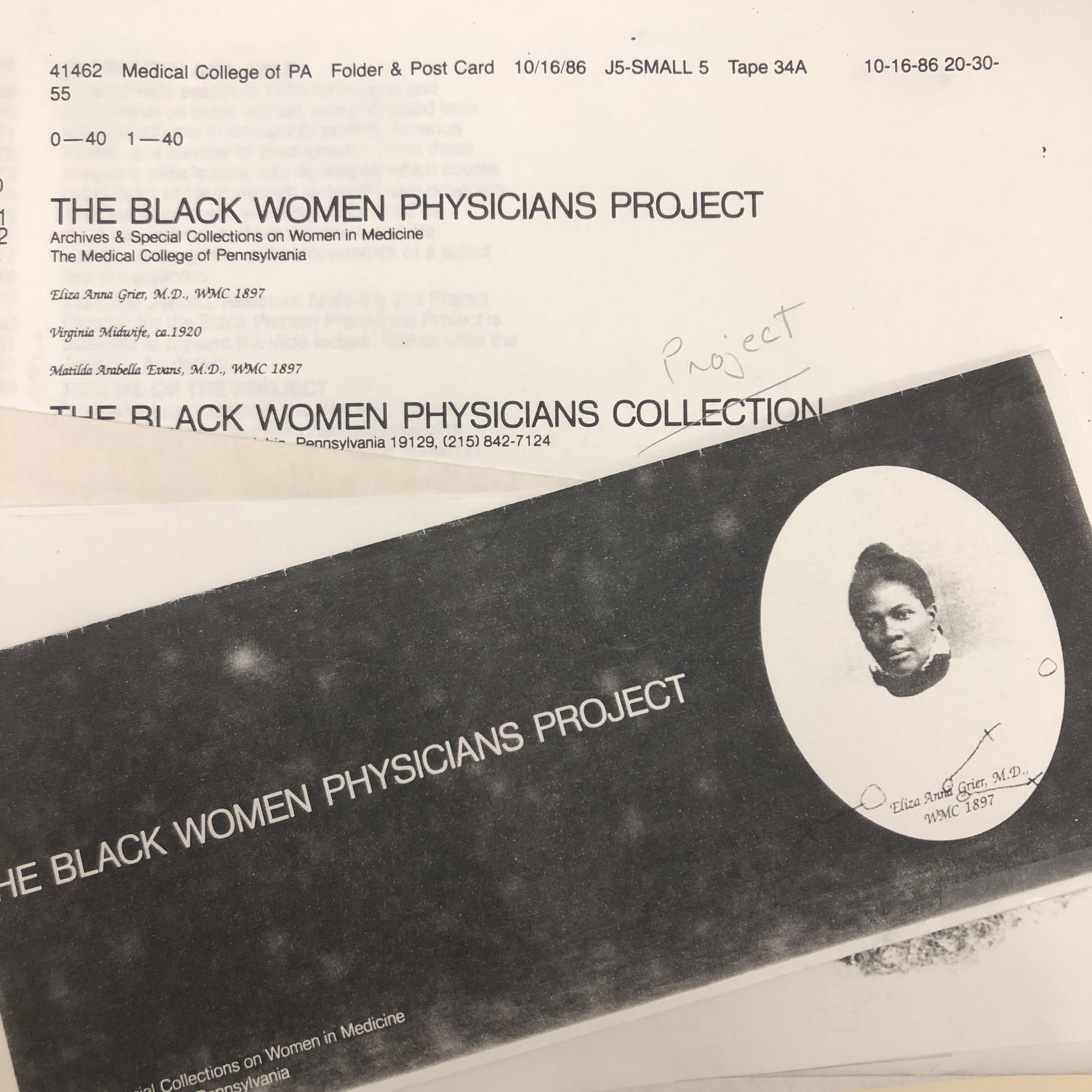

Promotional materials created for the Black Women Physicians Project, 1987

The archival field is increasingly pushed to reckon with the way in which our practices serve as a center for what Tonia Sutherland describes as the “privileging, preserving, and reproducing a history that is predominately white” (2017, 10). In response, archivists look toward ways in which they can fill in the gaps generated by archival practices, recognize how traditional archives replicate oppressive ideologies and make transparent the work that goes into repairing these inequities.

Reparative archives focus on the efforts described above, and are defined by Lae’l Hughes-Watkins as work that “does not pretend to ignore the imperialist, racist, homophobic, sexist, ableist, and other discriminatory traditions of mainstream archives, but instead acknowledges these failures and engages in conscious actions toward a wholeness that may seem to be an exercise in futility but in actuality is an ethical imperative for all within traditional archival spaces” (2018, 4). Such work can take the form of reshaping descriptive practices, advocating for the diversification of collections, and other actions that hold the archives accountable for the racism inherent to its practices, as well as actively seeking to rectify this harm.

Hughes-Watkins explores diversifying archival collections as an integral component of reparative archive work, shifting traditional practices that privilege certain records and perspectives at the expense of others:

“The diversification of analog and digital records in an effort to provide an all-encompassing panorama of America’s human story is critical to the process of healing the relationship between traditional archives and historically underrepresented communities.” (2018, 8)

The Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections at Drexel University College of Medicine holds a collection that predates our current idea of reparative archival work, but still demonstrates a goal of building a more inclusive and comprehensive narrative through the diversification of records. This collection is the Black Women Physicians Project (BWPP), an artificial collection started by archivist Margaret Jerrido in the 1980s. Starting in 1864 with Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first Black woman to graduate medical school in the United States, BWPP documents the lives and careers of Black women physicians. Since beginning my internship with the Legacy Center, I have been learning the practices that go into processing archival collections. Now working through BWPP as my second processing project, I’m paging through the documents that comprise this collection while recognizing Jerrido’s work as strides towards highlighting Black women in a narrative that otherwise obfuscates them. While this collection is striking in its aggregation of documentation of Black women physicians over the span of a century, viewing BWPP as a collection that also documents the work that goes into reparative archival work is similarly compelling (especially as something being done prior to Internet use being wide-spread).

The size and scope of the collection reflect how difficult it often was to find records of Black women in medicine. In the original accession record, Jerrido wrote:

“The material represented in this collection is scant, probably due to a number of factors: 1) primarily, relatively few black women chose to enter (or had the choice of entering) the white, male-dominated medical profession. Material on the black women who did become physicians would be limited then, to begin with; (2) published material about black women physicians is extremely difficult to find … ; and (3) manuscript materials for the black women who did become physicians is also scarce.”

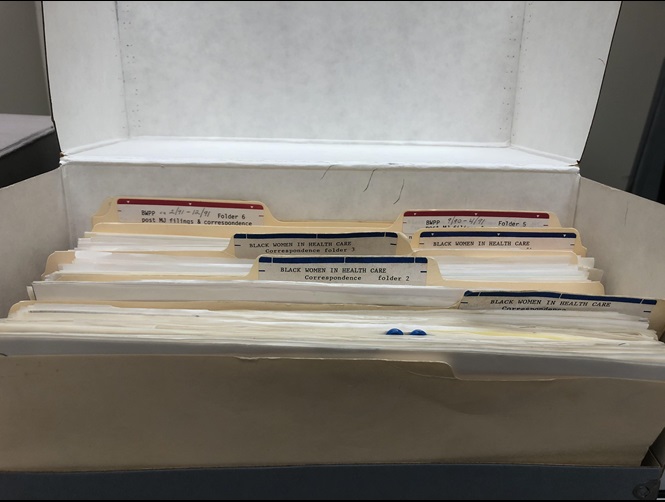

Working in the boxes

A large part of the collection–and certainly the part most engaged with by researchers–is made up of 166 Biographical Reference Files of varying degrees of richness, in addition to 69 more files that provide only the names of Black Women physicians. Beyond the Reference Files, the collection has a substantial amount of documentation relating to the correspondence with subjects and research that shaped these files. These records highlight how, for women who graduated from medical school and practiced at the turn of the 20th century, information is scant, and attempts by Jerrifo to locate documentation sometimes were unsuccessful.

Examples of the variation in richness can be seen in the file on Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens, who was the first Black woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons in 1950, and who taught and practiced in Philadelphia. Information on Dr. Dickens in the collection is vast, including materials like correspondence, news clippings, magazine features, in addition to a folder just for photos that chronicle both her professional and personal life. On the other side, there are numerous folders that contain only a physician’s name, location, and approximate practice dates, such as Julia Erluna Smith or Daisy Hill Northcross. The barest folders generally belong to women who had graduated from medical school and practiced in the late 1800s or early 1900s, further showing the scarcity of documentation for early Black women physicians.

Beyond learning the technical skills of processing and improving access to archival collections, it has been interesting to reflect on and engage with a collection that ensures Black women have a voice in the history of medicine. While reparative work in the archives can take the form of reframing how we approach description (whether new or old), equally important is working to widen the scope of perspectives celebrated in our collections. As BWPP shows us, highlighting the lives and stories of Black women physicians is an arduous task, especially as a project undertaken without the ease of online communication and research, and one that requires intentionality and diligence. With BWPP being one of the first collections I have processed in my archival career, not only did it teach me the intricacies of working with artificial collections, but also the value of approaching archival work through a reparative lens. Recognizing both the scarcity and often the omission of Black women from the medical narrative, BWPP serves as an invaluable example of reparative work in the archival field and showcases why it is important that such work continues evolving and moving forward.

—-

Resources on reparative archives & social justice in the archives:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8vyxQHMysk0

https://archivesforblacklives.wordpress.com/

https://countway.harvard.edu/news/describing-better-introduction

https://aotus.blogs.archives.gov/2022/01/18/guiding-principles-for-reparative-description/

https://www.uproot.space/features/the-house-archives-built

—

Sources:

Hughes-Watkins, Lae’l. 2018. “Moving Toward a Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for a Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 5, no.6. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol5/iss1/6

Sutherland, Tonia. 2017. “Archival Amnesty: In Search of Black American Transitional and Restorative Justice.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Services 2: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i2.42