Drexel undergraduate students are researching individually-chosen topics and using Legacy Center collections in their research, under the supervision of Professor Lloyd Ackert, Teaching Professor of History, and with the guidance of Legacy Center archivists. Each student is creating a blog post and adding to it as they progress with their work. Updated 15 August, 2022.

by Amanda Lyles, Research Co-op Student, 2021

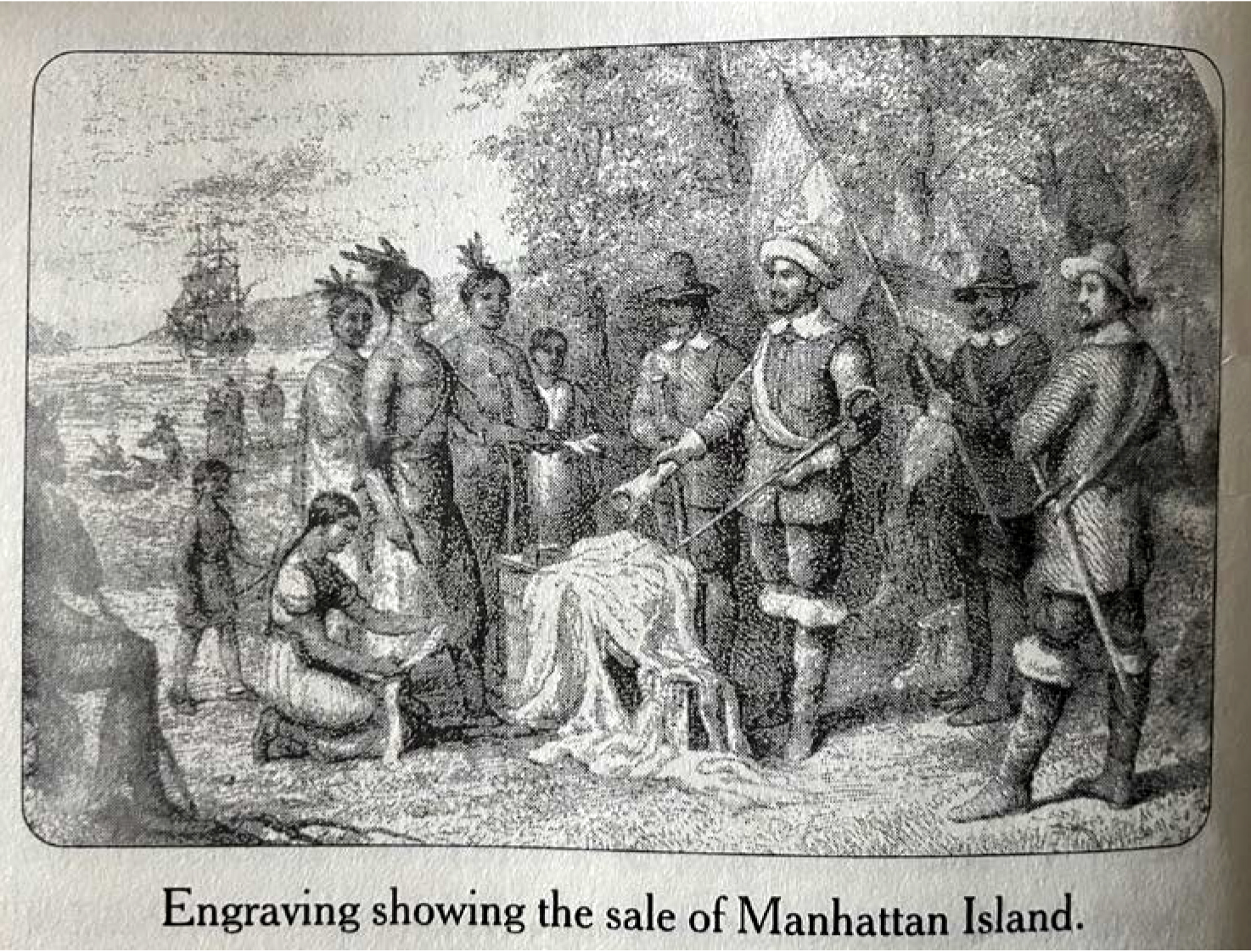

Engraving showing the sale of Manhattan Island. (Hearth, Amy Hill. “Strong Medicine” Speaks: A Native American Elder Has Her Say. New York: Atria Books, 2008. p.4)

“It was the Lenape who famously sold Manhattan Island for the equivalent of twenty-four dollars to the Dutchman Peter Minuit in 1626. (Historians now believe that the Lenape probably thought that they were “renting” or sharing a small portion of the island.)” (Hill, 2008, 4)

It was then in particular that the Lenape were put in a tough position in keeping peace. Little did they know that after their encounter with the Italian Captain by the name of Giovanni Da Verrazzano, sailing a French vessel in 1524, that it would not be long before the English would build a settlement in Jamestown; that there would be the arrival of pilgrims in 1620 at what would become Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, and that French, Portuguese, and English European explorers would follow with desire to claim land already inhabited by their people. Hill argues, "Time and again, the settlers cheated, lied to, and committed genocide against Indigenous people. An untold number of [natives] also died of diseases, such as small-pox and measles, to which they had no immunity” (Hill, 2008, 3). There is much to learn about various Indigenous communities' responses to harsh treatment, violence, and resulting policies that sought to eliminate and integrate Indigenous people. Hill adds, “as pictured here, the Lenape leaders, whose lands were especially coveted were thrust into a world they did not understand” (Hill, 2008, 3). This was a world that was forced upon them which took away Indigenous autonomy. In many instances, they would either experience the consequences of resistance or forced assimilation. Hill further adds, “Tragically, the abusive and murderous tactics used against the East Coast tribes called “Nations of First Contact” by Native Americans - would become the template for the way other tribes would be treated in the coming years as [colonists] moved ever westward” (Hill, 2008, 3).

In their resistance to the civilization process, Indigenous peoples of North America have prioritized their communities’ needs by refusing to compromise their identity and by supporting their communities in an effort to improve conditions and respond to the disparities stemming from poor treatment. Ultimately, Indigenous peoples have persisted in defining their self-determination within their survivance or active sense of presence.

Hello everyone! I’m Amanda Lyles, a senior undergraduate with a major in Behavioral Health Counseling and a minor in History at Drexel University. In my co-op I will be conducting research on the journeys of Indigenous women in medicine as early representatives of their communities who historically attempted to improve conditions and eliminate disparities as a result of the government’s mission to fully assimilate Indigenous peoples of North America. I will survey the forceful experiences and options two Indigenous women had to navigate and endure stemming from the civilizing process set in motion by federal governmental policies. As healers, representatives, and activists; Indigenous women in medicine demonstrated resistance that called for government responsibility and obligation by way of genuine intent for change during the Progressive era which ignited later movements. The responses of these two Indigenous women alongside other Indigenous physicians and activists such as Charles Eastman and Zitkala-Sa demonstrate just a handful of persistent measures and responses of an array of Indigenous communities seeking to collectively protect their communities from discrimination and inequality.