Modern Miracle Women: Dr. Catharine Macfarlane a Leader in the Fight Against Cancer

- Exhibit by guest blogger, intern Jessica Walker

Although routine pelvic and breast exams are standard now, that hasn’t always been the case. In the early 20th century, doctors commonly thought that healthy women wouldn’t submit themselves to periodic examination without cause. Dr. Catherine Macfarlane, however, thought that the modern American woman would, and she was going to prove it. In 1938 she received a grant from the American Medical Association to study periodic examinations to detect early appearances of carcinoma. The study lasted for 15 years. Dr. Macfarlane made a lasting impact on early cancer screening and prevention. Pelvic and breast exams are now a routine part of female physical health. Through the research clinic operated by Dr. Macfarlane, it was proved that early, routine examinations lead to early detection, and therefore treatment, of many types of cancers specific to women.

In July 1937 Catharine Macfarlane attended the Medical Women’s International Association Fourth Congress in Edinburgh, Scotland. There she participated in a discussion on the screening and prevention of pelvic cancer. She lamented that many of the doctors participating found it unlikely that women in their countries would not submit to preventative screenings. American women, she thought, would, and she set out to prove it by opening the first cancer prevention clinic in Pennsylvania, one of the first in the country.

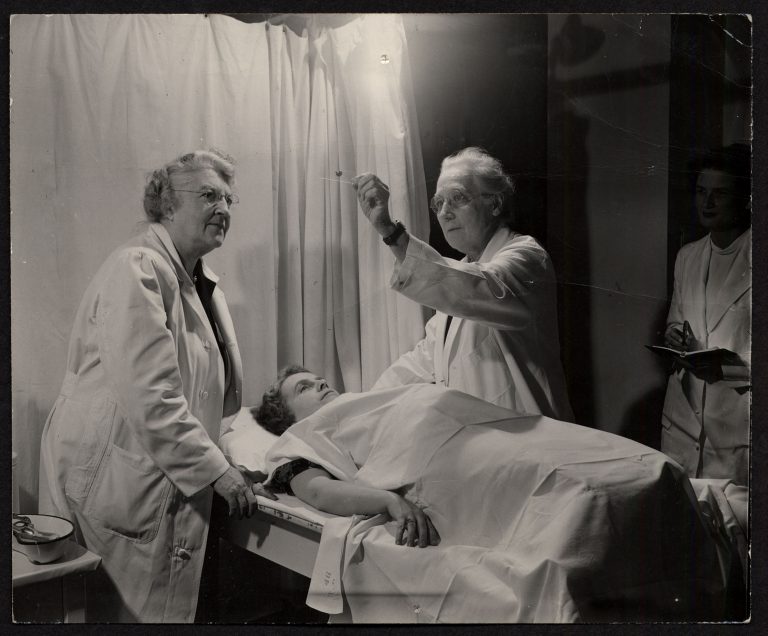

Dr. Macfarlane was often praised as one of the forerunners in the fight against cancer. The Cancer Control Research Clinic operated by herself, Dr. Margaret Sturgis and Dr. Faith Fetterman began in 1938 and involved a study of over 1,300 women. By the time Dr. Macfarlane closed the research clinic, over 200 such centers existed around the country.

Throughout the study, Doctors Macfarlane, Sturgis and Fetterman published several articles on their findings from the clinic. This was one of the first articles, published in the Medical Women’s Journal in 1942.

Doctors Catharine Macfarlane and Margaret Sturgis at the Cancer Control Research Clinic, circa 1959

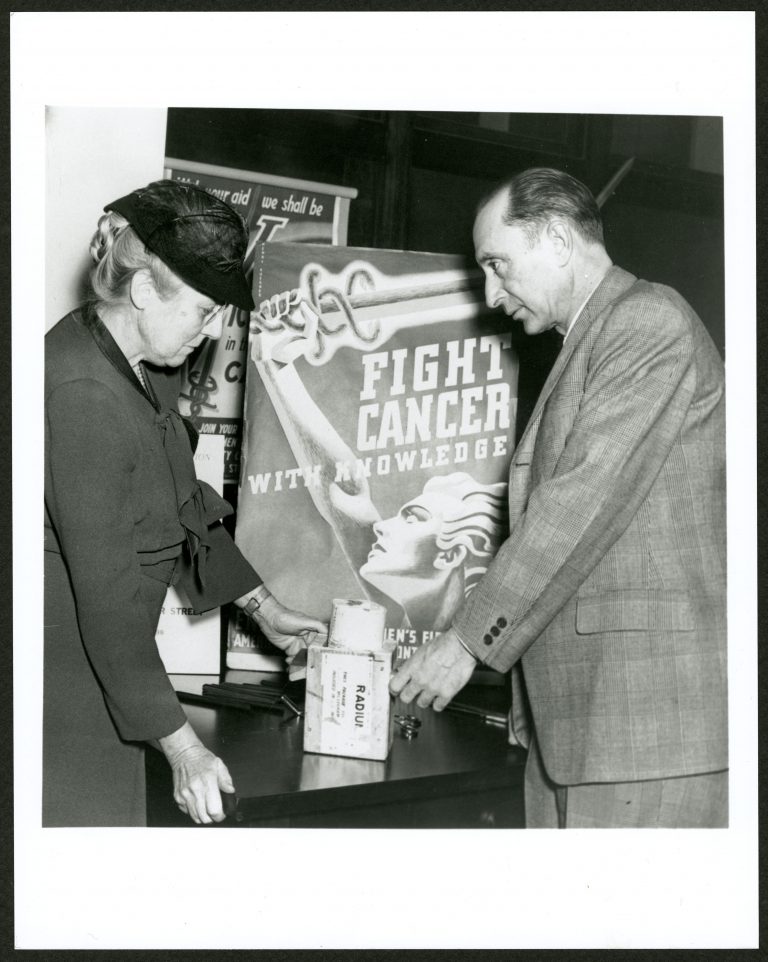

In addition to doing the work of research on the positive effects of early screenings and writing papers, Dr. Macfarlane also gave talks on the results of the cancer prevention clinic.

Doctor Macfarlane at an exhibit on cancer, circa 1949

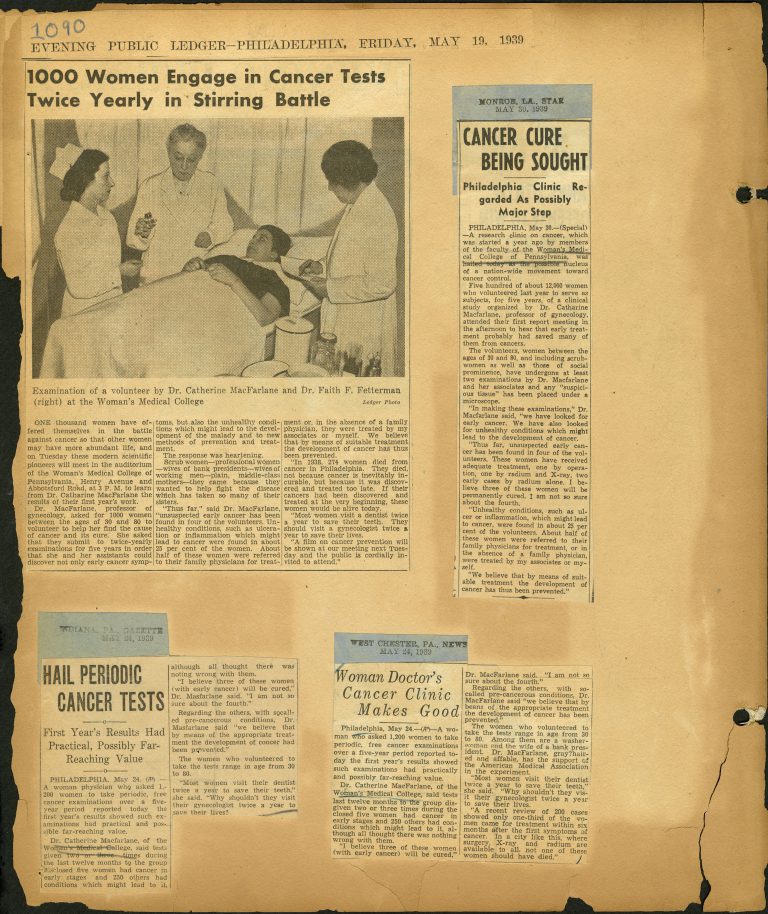

Despite what the doctors at the MWIA meeting thought, women in American were willing and eager to participate in preventative screenings. The experiment was a resounding success. It drew the attention of not only medical professionals, but laypeople as well. The results of the prevention clinic were reported on by newspapers and magazines from around the country.

from the Cancer Bulletin, circa 1951

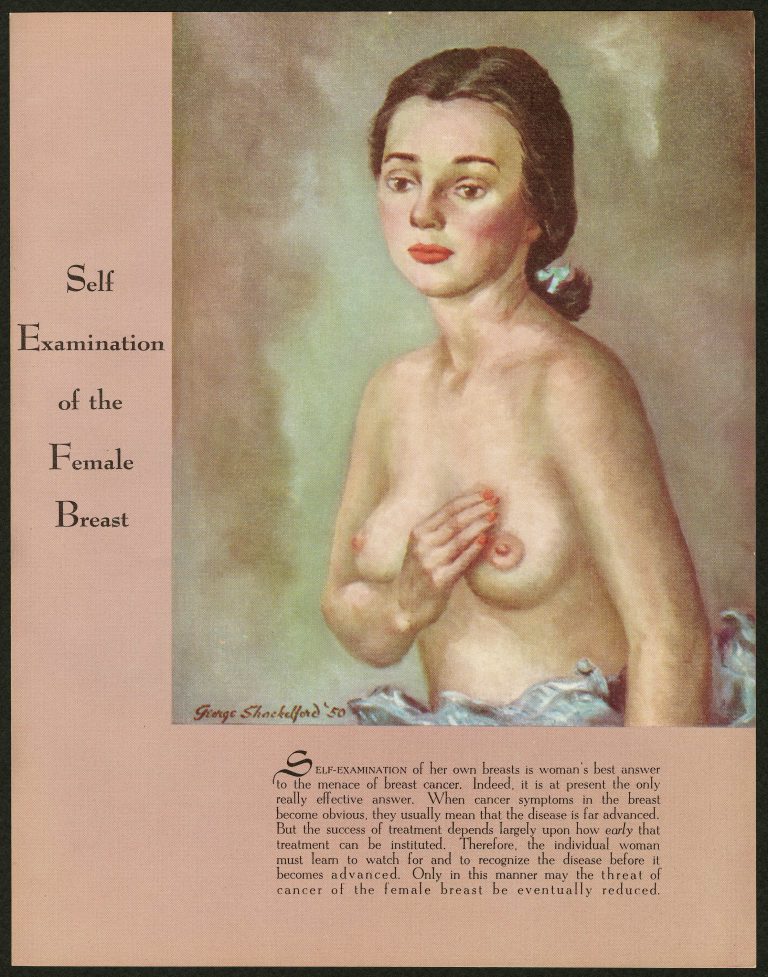

Though her initial focus was on pelvic exams, Dr. Macfarlane expanded the focus of the research clinic in the 1950s to include a study of breast exams and self-examination performed by the women themselves. She found that women were able to detect abnormalities just as soon as a doctor could.