Working with the Sources: The American Women’s Hospitals in the Near East

Virginia Metaxas

Professor of History and Women’s Studies

Southern Connecticut State University

In a general way, the history of this part of the earth's surface may be divided into three periods: before the Turk, under the Turk, and after the Turk. Long, long before the Turk, the spiritual and intellectual life which survives in our present day western world, divinely planted in the minds of men, developed in the southern section of the Balkan Peninsula, the Ægean Islands, and along the coast of Asia Minor. This is the glory that was---and is Greece. 1

What is the civilized world going to do about…[the Turkish government’s] steady oppression” of the Armenians and “the deportation” of so many of the Greeks?2

The retreating Greek Army left Smyrna on September 8, 1922; the Turkish army occupied the city on September 9; and the fire was started on September 13.3

The largest American Women’s Hospitals projects in the 1920s and 1930s were in Greece, where long term medical aid was desperately needed, due to the devastation left by the First World, Balkan, and Greco-Turkish Wars. To meet the vast needs for medical relief, President Esther Pohl Lovejoy found that she had to spend much of her time fundraising. As early as 1919, she realized that she needed to capitalize on human interest stories as well as factual material in order to procure private and public support of the AWH projects. In a letter written to Dr. Ruth A. Parmelee, a physician and medical missionary working in Harpoot [now Harput] Turkey, Dr. Lovejoy succinctly said:

We are very much interested in the work you are doing and we should greatly appreciate a more complete description of the cases you are meeting. I observe that your total number of treatments for the month of August was something over three thousand. It is very helpful in this office to have letters descriptive of conditions that are of human interest. In other words, stories of suffering and heroism such as will help us in our effort to secure funds to continue this work.4

Dr. Parmelee, who served in Greece for three decades in various capacities under the auspices of the AWH, took Dr. Lovejoy’s advice to heart. She became, in a very real way, an impassioned advocate for the continued support of the Christian Greeks and Armenians she worked among both in Turkey and in Greece. Without exaggeration, Parmelee was one of the most articulate reporters of conditions witnessed by AWH staff abroad. Having grown up in Turkey, the daughter of missionary parents, and a fluent speaker of many of the Near Eastern languages (Armenian, Greek, Turkish), she may have had a particularly empathetic feeling for the people with whom she worked. Through her four decades of work in Turkey and Greece, she sent a constant stream of information from the field to the AWH office in New York, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in Boston, other professional medical women’s organizations, and to the general public in the form of medical reports, professional and newspaper articles, books, private and public letters, speeches, lectures, and more. Dr. Lovejoy was supreme at this sort of activity, publishing three major books and hundreds of professional and lay articles, giving speeches and lectures, and participating in other promotional activities too numerous to count. She required all of the AWH physicians working in the field to send statistical data as well as ‘stories’ for use in publicity materials used for fundraising. These abundant and varied materials, many of which are located in the Records of the American Women’s Hospitals, are a windfall to historians seeking documentation of the work of the AWH. It is also the task of the historian to identify biases in sources and to situate their significance in a larger context.

Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy, 1918.

Dr. Ruth Parmelee and nurse. Salonica, Greece, 1922.

Lovejoy’s and Parmelee’s work in reporting what they saw and heard, and their calls for support and action, built upon a tradition set in motion earlier by secular and missionary Americans who had served in various Near Eastern locations. In the context of rising nationalisms in the region, Americans had witnessed many years of conflict between the Muslim Turks, who they often characterized as feared, despised, and uncivilized “Mohammedans,” and Greeks and Armenians, who they characterized as “Christian martyrs,” especially in the context of resistance to Ottoman rule. Indeed, late nineteenth and early twentieth century reports from American missionaries and diplomats had resulted in widespread public awareness of the plight of Armenians and Greeks in the waning final years of the Ottoman Empire. Many grassroots organizations, both religious and secular, conducted massive public fundraising campaigns so that American citizens knew of and contributed to saving the thousands of “starving Armenians” displaced by the conflict in the area.5 The Greek genocide and forced population exchange of 1922 became part of the American consciousness through the efforts of American witnesses who sought to form public attitudes and possibly achieve humanitarian intervention. These unprecedented international human rights campaigns helped shape America’s national and international identity.6 AWH fundraising efforts shrewdly adopted these familiar tropes as a means of obtaining the funds to provide medical relief. They joined the chorus of voices speaking against the growing evidence of ‘Turkification’ perpetrated by the Kemalist government, policies that resulted in the ethnic cleansing of Christian populations in the region.

Esther Pohl Lovejoy, President of the American Women’s Hospitals since 1919, assigned AWH staff to Greece in 1922 after witnessing the burning of the city of Smyrna and the “violence and chaos [that] marked the beginning of [the] forced migration of Christian people...from Turkey.” 7 In 1922, when the General Secretary of Near East Relief Charles V. Vickery said that “unforeseen radical changes in the political, racial and military maps of the Near East” occurred during the previous year, he summarized events succinctly. Although the First World War had supposedly ceased, war between Greece and Turkey endured. “Races,” he said, had been “transplanted.” Peace conferences failed, leaving political stability in the region unsteady at best. Refugees, both Christian and Muslim, were thrown into exile, forced from what he called their “ancestral homes.” Thousands of new orphans, above and beyond those already in existence, were created by the death of parents and relatives during the “exchange of populations” between Greece and Turkey. In short, the demands for emergency relief work had multiplied “by military victories and disasters, devastating fire and the cruel interchange of population.” 8

James L. Barton, one of the founders of the philanthropic organization Near East Relief, later said that the tragic events occurring in this period represented “international diplomacy at its low ebb.” 8a

Similarly, members of the Board of the American Women’s Hospitals realized they had to react to the Smyrna disaster and the large number of refugees flooding into Greece. In 1922, members of the Executive Board of the American Women’s Hospitals met in Geneva, for a conference of the Medical Women’s International Association. Present at the conference was Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy who was then President of the Medical Women’s International Association and one of the founders of the American Women’s Hospitals. Dr. Lovejoy was no stranger to conditions in the Near East; she had overseen the establishment of American Women’s Hospitals in the region since AWH personnel first went there in 1919.9 Also present at the conference were other American women physicians who had been working in the region, including Dr. Etta Gray, AWH Director in Serbia, and Dr. Mabel E. Elliott, AWH Director in Armenia and Turkey.10 Dr. Elliot’s valuable input on current conditions in Turkey was based upon years of recent experience there.

Dr. Elliot had been in Turkey since 1919, and was among the same group of relief workers that arrived with Dr. Parmelee immediately following the end of the First World War.11 Due to the ongoing internal conflicts taking place within Turkey, she had been forced to move operations to at least three different places between 1919 and 1922. Dr. Elliot was first assigned to the area of Marash, far into the interior of Turkey, where she took over a German missionary hospital, ran a clinic and worked with orphans.12 Twenty five thousand Armenians who had survived the state-required 1915-1916 deportations had begun to return to their former homes in Marash, feeling secure because British troops monitored the area. By 1920, though, the British pulled back and the Kemalist authorities began to be hostile towards the Armenians and Americans there. Dr. Elliot fled, along with thousands of Armenians, from the area. 13

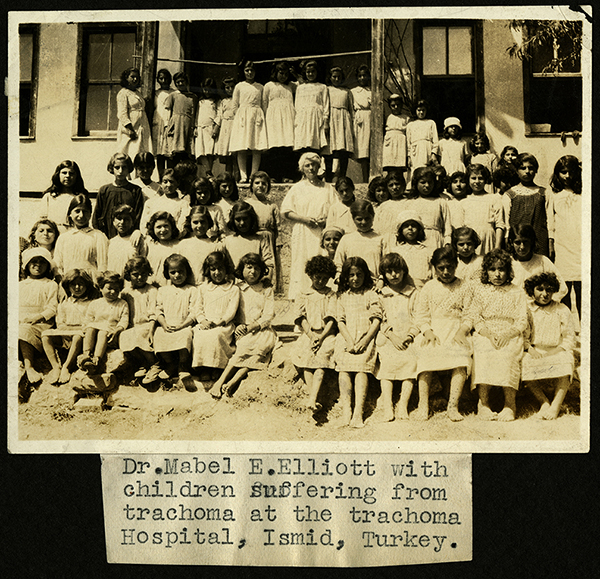

She was then assigned to the area of Ismid (Izmir), along the coast and about fifty miles from Constantinople, where British, French, Italian and American ships lay in the harbor, again providing some degree of security. Thousands of refugees poured into Ismid, “scurrying before the rumour of Turkish advances like leaves blown by a rising storm."14 By 1921, her work expanded to include Erivan and the Caucasus region.15 Dr. Elliot described this expansion of work by saying that they had taken over all the medical work in the Derindje, Bardazag, and Ismid regions, that there were 25,000 refugees in Ismid alone and 5000 in Derindje. They ran a large boys’s orphanage in Bardazag and a girl’s orphanage at Ismid, a seventy-five bed general hospital, a fifty bed children’s hospital, a trachoma hospital, a smallpox camp, and several clinics.16

Trachoma Hospital, Ismid, Turkey, circa 1920.

The work was overwhelming, and by late 1921, Dr. Elliot reported to the American Women’s Hospitals that in spite of all that they were doing, misery reigned. “Since I have been here, 852 is the lowest number of cases we have had in our hospitals, and yet they are dying on all corners of the city.” She was forced to turn people away, in order to try to save those who were already in the hospital. “There is no use in crowding them in so that they will all die,” she concluded reluctantly.17

Similarly, she could not possibly accommodate the needs of the city’s orphans. In January, 1922 she said that children were dying daily in droves. “All day long we can hear wails and groans of little children outside [the] office building hoping we can and will pick them up. One day rain turned to snow [and] it was awful to listen to them. The note of terror that came into general wail was plainly perceptible upstairs and I had the windows closed. We are picking them up fast as possible but fatal to crowd them to such a point we would lose even those already in orphanage." 18

In 1922 at the Geneva meeting of the American Women’s Hospitals, Dr. Elliot was given a new assignment in Constantinople, and Dr. Lovejoy was instructed to go to Russia to discuss a projected joint project with members of the American Friends Service Committee. Constantinople had been occupied by the Allies since 1920, and was a city filled with hungry and sick Greek and Armenian refugees. Dr. Elliot went to Constantinople to get to work, and Dr. Lovejoy went to Paris to prepare for her trip to Moscow, but then she heard news that made her change her mind. The Kemalist government had sent word to the League of Nations “alluding to the atrocities said to have been committed by the Greeks in Asia Minor [during the recent hostilities], and disclaiming “all responsibility for consequences that may arise from these terrible provocations.”

Dr. Mabel Elliot in 1920

Expecting a bloodbath of the Christian minorities as the Turkish army pushed toward the Aegean coastal cities, she cancelled her plans to go to Russia and instead went straight to Constantinople. Dr. Elliot met her at the station when she arrived, and they decided that they had “both heard and answered the same call.” Dr. Elliot almost immediately left Constantinople for Rodosta, Eastern Thrace, accompanied by her head nurse. An exodus had begun, and they were on their way to aid eighty thousand “refugees [who] had been landed from the Turkish side of the Sea of Marmora.” There they started hospitals, clinics, and milk depots with the help of local governments and the American Red Cross. In the meantime Dr. Lovejoy met with Admiral Bristol, an American in charge of the Disaster Relief Committee in Constantinople, to discuss pooling their resources. She then boarded the ship Dotch heading straight for Smyrna. There she would witness the culmination of the protracted hostilities between the Christian and Muslim populations of Turkey in the place she called “the martyred city.” 19

Many witnesses wrote about the Smyrna disaster, outraged by what they saw there, especially because the brutalities were experienced by Christians. Upon seeing it from the harbor in September, 1922, Dr. Lovejoy’s first impression was one of shock. This was the second time she had been to Smyrna, having stopped there once before in 1904, while on the way to a World’s Fourth Sunday School Convention which was meeting in Jerusalem. It was then that she had learned of the city’s long history of lootings and burnings by “hordes of barbarians and others from Europe and Asia.” Because the city had a prominently Christian population, she said, the city had been known by the Turks as Giaour Ismir, infidel Smyrna. “Polycarp, the first bishop and patron Saint of Smyrna, was burned for his faith in the year 155 A. D,” she said, “and the story of his martyrdom was told over and over again in sermons and lectures.” As she stood on the deck of her ship and smelled “the stench of dead Smyrna in [her] nostrils,” and saw the flying Turkish airplanes flying overhead, and realized that two-thirds of the city had been burned to the ground, she wondered of “the followers of Polycarp and his followers [were] in vain.” 20

Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy arrived in Smyrna as the people crowded on the quay, and she immediately began to give medical aid to the sick and wounded--even delivering some babies out in the open. “Never were babies brought into the world in stranger and sadder surroundings,” she later said. “We delivered many babies on the quays, while streams of panicked humanity surged around us. A thin white line of American sailors protected the laboring mothers from hundreds of human beings fighting desperately to pass the barriers to the boats. Some babies were born alongside the gangplanks of departing ships. One young mother gave birth to her first child as she stood in line, fearing to give up her place.” 21 She spoke of the way the refugees were robbed on the waterfront “by Turks, soldiers and civilians” as they tried to embark waiting ships. “The Turks were pawing them over, women and men, searching through their clothes for any money or valuables that they might have on them.” Most poignant was her telling of how children threw “their arms about the legs of their fathers and [shrieked] for mercy, and of wives clinging to husbands in a last despairing embrace.”

The Christian population on the Smyrna quay. September, 1922

Greek refugee ship leaving Smyrna. September, 1922.

Equally as cruel was the widespread rape of women which occurred at Smyrna, later to be described by Dr. M.C. Elliot of the American Women’s Hospitals who cared for many of the survivors in Athens. Many were carried off as well, numbering higher than 50,000 according to a later League of Nations report.22 Dr. Lovejoy spoke of the “quiet of night [being] rent by the piercing cries of young women who are being taken by Turkish soldiers. I never believed such things could happen," she said. 23

Despite the fact that nearly 250,000 people clung to life on the waterfront, the Allied ships maintained neutrality. Nearly 30,000 people perished in the Smyrna disaster.

Henry Morgenthau, the first chairman of the Refugee Settlement Commission organized by the League of Nations, tried to explain the causes of the great exodus of the Greek people from Asia Minor. It seemed obvious to all then that the atrocities that occurred in Smyrna “were clear evidence of the deliberate intention of the Turks to remove utterly all Greek population from Asia Minor,” in order to make it “completely Turkeyfied.” Within a few weeks of the Smyrna disaster, 750,000 fleeing refugees from all areas of Asia Minor–the vast majority of which were women and children without male support-- arrived at the ports of Salonica and Athens, and on the islands of Crete, Mytilene, Chios, and Euboea, in terrible condition. Hungry and sick, with few resources, they suffered with diseases such as typhoid and smallpox. The crowding and unsanitary conditions produced by their trek left most infested with lice. Some were so depressed they committed suicide, throwing themselves overboard, unable to cope with their losses. They were without shelter, blankets, or clothing–and in desperate financial ruin. They numbered over a million in total, and Greece, a poor country of approximately five million people, had to find a way to aid and absorb this desperate population, their Asia Minor compatriots. 24

Just prior to this massive evacuation of Christian populations from Turkey, Dr. Ruth A. Parmelee was on a “flying summer visit” to the U.S., making preparations (fundraising) to open “medical work in Smyrna for Turkish women.” While traveling back to Turkey and still on the Atlantic, she heard the news of the “great fire in Smyrna” and that her services would instead be needed “in some other region.” The AWH engaged her to go to Salonica, (Thessalonika) and she traveled there “on a steamer filled to overflowing with people fleeing from Constantinople” who were “in great panic, fearing a disaster similar to that of Smyrna.” 25At this point, even though Dr. Parmelee still identified herself as a missionary physician, she worked under the auspices of the secular AWH. She considered herself to be “loaned” to the AWH and the NER by the ABCFM.

But this is not to say that the AWH was a completely secular organization. In the first years of the 1920s in particular, their publicity campaign for fundraising used mildly religious rhetoric and sometimes explicitly holy images that would appeal to the American public’s sympathy to save the thousands of women “bereft of husbands and sons and driven from home,” and the orphans they called the “sacrificial lambs [of] this generation.” 26

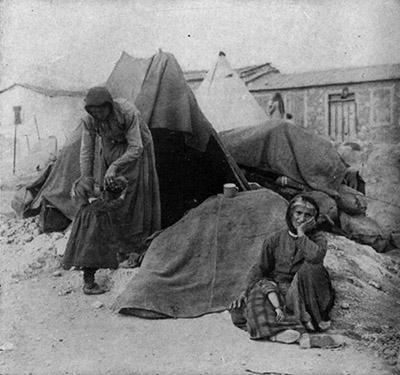

Bereft of husbands and sons, and driven from home. (From Lovejoy's "Certain Samaritans")

"Sacrificial lambs, of this generation"

Equally as important is a narrative of motherhood they created for the purposes of obtaining financial support of the much needed relief projects. Take for example the photograph presented below depicting Dr. Parmelee standing over a Greek refugee woman and her baby. 27

This photograph is one of many gendered representations of Christian Greeks (and sometimes Armenians) that the AWH used in order to raise sympathy and financial support for relief aid in Greece during this time. What we see here is a typical Greek Orthodox Christian image—that of Madonna and Child—which of course implies religious connotation about the sacredness of the relationship between mother and child. This AWH publicity photo was deliberately meant to stir the conscience of prospective donors who would contribute funds to the medical projects needed in post-disaster Greece.

But notice the figure of another woman—in this case a Protestant secular woman—Dr. Parmelee to be exact. For Dr. Parmelee and many other medical women involved in this relief work, saving the lives of women and children was particularly important—and while creating a narrative of motherhood which would appeal to American donors and sympathizers was vital to continuing support for relief projects, so was it important to reinforce the authority of women doctors in getting the job done. Thus the image also speaks to possibilities about Dr. Parmelee’s self-identity—that of woman doctor and child saver—that of scientist and humanitarian.

Indeed, the theme of the persistence of birth and motherhood even in the face of disaster dominated the messages from American women doctors in the region. Dr. Lovejoy, in particular, focused on this type of narrative, at times on behalf of NER and other times for the AWH. After her traumatic experience at Smyrna, where she delivered infants as the chaos of the burning of the city and the evacuation raged, she wrote how in her view “motherhood transcends the destruction of men.” “Since the beginning of the world men have warred for property and power and women have patiently renewed what they have destroyed, --human life,” she said. 28

And furthermore, she noted that “[b]eing a refugee does not preclude the sacrifice and glory of motherhood. Neither hunger, nor thirst, pestilence nor cruelty, not even the spectacle of the waste men make of life, can deter woman from her profound function. Dumb, patient, loving, women mother the world. When will men, to whom war is a game, waken to an appreciation of their own precious humanity that will equal the generosity of inexhaustible motherhood?” 29

Certainly the medical women working in Greece had plenty to do to aid these ‘mothers of the world,’ and the scores of children that came with them. By 1924, the AWH staff had conducted thirty-four hospitals in Greek territory, including hospitals for the Armenian orphans brought to Greece by the NER. From January to June 1923, as the fleeing refugees swarmed over from Turkey, they set up a quarantine station and hospitals on Macronis30

Four months after Smyrna, and upon her return to Greece after a fundraising trip to the U.S., Dr. Lovejoy visited the quarantine island at Macronissi to see refugees coming ashore—“a tragic procession made up of women, children, the aged, and a small proportion of able-bodied men, struggling through the sand with their bundles on their backs.” They were sent to the camp of the “unclean” until they were deloused and their belongings disinfected. Dr. Lovejoy described the women, whose husbands had probably been “detained” as strong and determined to survive. “There were no weaklings in this brood…Who was she? No one knew. What was she? Everyone knew. A strong mother, an honor and an asset to her people…She was not resigned to her fate…Her spirit was not crushed. Hagar, mother of Ishmael, might have had just such a proud, resentful face.” 31

Dr. Parmelee later wrote that upon her arrival in Salonica in October 1922, she found “the city teeming with newly landed refugees and hundreds pouring in, day by day.” Any and every building was crowded to the limit. While the American Red Cross “carried on” a sanitation project and “a feeding campaign for about six months,” it was the AWH doctors and nurses who did the majority of the medical relief.”32 By the end of December 1922, Parmelee reported that nearly one hundred and forty thousand refugees settled in and around the city of Salonica. 33

Dr. Parmelee focused on maternity care, saying that “thousands of babies are being born on the road, on the steamer, or after the arrival here, with no provision whatever for the comfort and necessities of the poor mother and infant.” She reasoned that the new hospital, financed through the AWH, would “provide accommodations for women needing this care” as well as “give employment for a dozen nurses, and several doctors, to say nothing of the servants and attendants—all, refugees, and in need of employment. 34

While she ministered to the bodies of the refugees, and tried to provide jobs for some as well, other missionary colleagues paid attention to the spirit. Missionary schools and churches in the city opened their doors to aid refugees, and also planned along with the Greek government an orphanage to be located in a former monastery. 35 In an appeal to the American public, she spoke of “the most effective and popular worker among the refugees…Mr. American Dollar,” without whose assistance, she said, the “Near East Relief could not have cared for the one hundred thousand orphans that have been fed and clothed…since the Great World War.” 36 She went on to say that it was up to Americans to “care and help relieve the misery and suffering” indefinitely, until the “barbarities” that drove a million and a half people from their homes ended. She pledged that “[w]e who are on the Front Line plan to remain on our post as long as God gives us strength for our work”—and she did just that, for decades to come.37

These many examples of the ways in which the AWH physicians framed the story of Near Eastern Christian peoples’ struggle with war, famine, disease, persecution, property loss, poverty, and displacement, over time, persuaded Americans to donate millions of dollars of supplies and personnel to provide relief in Greece for a number of years after the initial crisis period passed. By 1924, the AWH staff had conducted thirty-four hospitals in Greek territory, and money was needed to keep up this necessary work. Dr. Parmelee remained in Greece for thirty more years, giving living proof of the commitment AWH made to this difficult but rewarding work.

Hundreds of photographs of these services are extant and held in the Records of the AWH at the Drexel University College of Medicine Archives and Special Collections on Women in Medicine, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The photographic and textual materials together provide overwhelming evidence of commitment and service contributed by the American Women’s Hospitals—those women at home raising money and those in the field actually doing the work. But there is no denying the importance of the steady feed of information sent by those in the field which provided the human interest aspect, so crucial to fundraising. Further examination and analysis of these materials is needed to fully understand the ways in which they help us to understand the extraordinary transnational humanitarian work conducted by American medical women in the Near East in the first half of the twentieth century.

The material raises many questions. How did AWH work, in conjunction with other agencies in the field, influence U.S. and international political relations and actions? Was Dr. Lovejoy’s aspiration fulfilled when she said in 1919 “we all feel that the medical women doing relief work overseas are not only doing relief work but are putting the medical women of the United States on the map of the world…?”38 How did the women connected to the American Women’s Hospitals manage relationships with other organizations laboring in the field, including local governments, the Red Cross, the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions, and Near East Relief? How does this study help us to understand the motivations that drove American medical women to leave the United States and work overseas? How did AWH rhetoric, in the context of war and growing nationalism in Greece and Turkey, feed into discourses about Near Eastern populations in the first half of the twentieth century? What sort of gender discrimination did AWH physicians experience? How did AWH women shape gender narratives in efforts to promote their work and raise support? These and more questions will be addressed as the work progresses.

1 Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, (New York: Macmillan 1927), 2.

2 Ruth Parmelee, typescript, “Relief Work at Harpoot, Turkey, 1919-1922,” 5, in Ruth Parmelee Paper s, Box #2, Folder, Correspondence, Selected Reports, Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California.

3 Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 142.

4Italics mine. Letter to Dr. Ruth A. Parmelee from Chairman EL (Esther Pohl Lovejoy), November 26, 1919, Records of the American Women’s Hospitals, Acc. 144, Box 9, Folder 73. The Records of the American Women’s Hospitals are located at Drexel University College of Medicine, The Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections, Philadelphia, PA 19129. Thanks to the generosity of the M. Louise Carpenter Gloeckner, M.D. Summer Research Fellowship, I was able to spend several weeks at the archives during the summer of 2010. I am very grateful to have received this support and for all the wonderful help of the staff there, including Joanne Murray, Director, Margaret Graham, Digital Resources Archivist, Lisa Grimm, Assistant Archivist, (who left shortly after I arrived) and Karen Ernst, Administrative Assistant. Their expertise and welcoming ways made my stay there very productive and joyful.

5 A recent treatment of the Armenian genocide and the response by the American public and government can be found in: Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response (New York: Harper Collins, 2003).

6 See Barbara Reeves-Ellington’s dissertation “That our daughters may be as corner stones: American missionaries, Bulgarian nationalists, and the politics of gender” (Graduate School of Binghamton University State University of New York, 2001) for a critical study of the role of American women missionaries in shaping U.S. ambitions for empire during the nineteenth century in the Ottoman Empire.

7 Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Women Physicians and Surgeons, National and International Organization: Twenty Years with the American Women’s Hospitals, A Review (Livingston, New York: Livingston Press, 1939), 121.

8 Charles V. Vickrey, General Secretary, Near East Relief A Review for 1922 (Annual Report to Congress) (New York: National Headquarters, 1923), 3.

8a James L. Barton, Story of Near East Relief (1915-1930) (New York: Macmillan, 1930), 139.

9 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 36-131.

10 Lovejoy, Women Physicians,117.

11 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 73.

12 Mabel Evelyn Elliott, Beginning Again at Ararat (New York, Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1924), 62.

13 Elliott, 98-121; Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 83.

14 Elliot, 144-145.

15 Lovejoy, Women Physicians, 107.

16 Lovejoy, 94.

17 Lovejoy, 98.

18 Mabel Evelyn Elliot, “Extract from message just received from Dr. Elliot Director of American Women’s Hospital Erivan,” Copy of incoming telegram to Near East Relief, Papers of ARA European Relief, Box 646, Folder 20, Near East Relief, Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

19 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 132; Lovejoy, Women Physicians, 118-119; 121-123; 138-141.

201 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 136-139.

21 “Smyrna! Where Motherhood,” 18.

22 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 113-118.

23 Ibid., 18.

24 Morgenthau, An International Drama (London: Jarrolds, 1934),51-55.

25 "Address given presumably in 1926” in Parmelee Papers, Box #2, Folder American Women’s Hospitals Relief Work.

26 “Bereft of Husbands and Sons, and Driven from Home” and “Sacrificial Lambs (This Generation) are the titles of two photographs appearing in Certain Samaritans, opposite page 269. The first photograph shows two three generations of refugees: a mother feeding her child, and a grandmother sitting forlorn on the ground, with another child asleep on her lap, all in front of a tent with a few covered belongings nearby. The second photograph shows a dozen emaciated but clean and shaven small children sitting on a bench at a clinic of some sort.

27 Photograph printed in Certain Samaritans, opposite page 322.

28 “Smyrna! Where Motherhood Transcends the Destruction of Men” in The New Near East, November 1922, p. 18. The article does not cite an author, but since Dr. Lovejoy was the only American woman doctor there on the quay during the disaster, and since similar descriptions appear in her other writings, I made the assumption that she is the author. See Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 136-175.

29 Ibid.

30 29 29 Ruth A. Parmelee, “Address given presumably in 1926” cited above, 2.

31 Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans, 227-229.

32 Ruth A. Parmelee, “Refugee Work in Salonica, Greece October 15-December 31, 1922” in Parmelee Papers, Box #2, Folder AWH Relief Work, p.1.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid., 2.

35 Ibid., 3.

36 Ibid., 4.

37 Ibid., 5.

38 Letter to Dr. Mabel M. Elliott from Esther Pohl Lovejoy, November 7, 1919, Records of the American Women’s Hospital, Box 14, Folder:114, Near East, 1919-1924.