Unlocking the Procurement Economy: Lessons from San Antonio and El Paso

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

February 8, 2024

(co-authored with Bruce Katz, Domenika Lynch, Victoria Orozco, Milena Dovali and Benjamin Weiser)

Over the past several years, the Aspen Institute Latinos and Society Program and the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University have dedicated countless hours to one central goal: using the expanding Procurement Economy to grow small local businesses, particularly those owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.

Our collaborative effort has been driven by the substantial increase in federal spending, spurred by the successive enactment of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act, the $411 billion Inflation Reduction Act and the $800+ billion (and rising) annual Department of Defense appropriations.

These unprecedented resources are reshaping the US economy in profound ways, accelerating the reshoring of production and the decarbonization of major sectors of the economy. If harnessed, federal spending and the economic restructuring it has capitalized, could create an historic, tantalizing opportunity to grow small, local and minority-owned businesses at a scale that enables the building of prosperous and inclusive metropolitan economies and builds wealth for owners, workers and communities alike.

Our partnership has occurred against a backdrop of stark gender, ethnic, and racial disparities in business ownership in the United States. At the national level, 20% of all employer firms are owned by women, 6% by Latinos, and 2% by African Americans, despite comprising 50%, 19%, and 13% of the population, respectively. These disparities partially explain the wealth gaps that hold back the performance of our overall economy.

As we have acknowledged before, unlocking the Procurement Economy is easier said than done. Federal funds are flowing through a complex maze of block grants, competitive grants, low-cost loans, tax incentives and direct contracts to a broad array of state and local governments, public authorities, private corporations, energy and water utilities, universities, builders and more. Beyond fragmentation, existing procurement systems, particularly in the public sector, are overly legalistic, inordinately bureaucratic and driven more by compliance than performance. Recent judicial decisions complicate matters further, compelling communities to emphasize supplier development rather than supplier diversity.

The only unifying thread across this labyrinthine system is place. Federal resources ultimately come to ground in real communities, predominantly cities and metropolitan areas, to buy real things. The procurement of goods and services, whether by federal agencies, general-purpose local governments, specialized public authorities or private utilities and manufacturing companies, ultimately determines whether our economy is tilted heavily towards a narrow set of large national conglomerates or a broader array of locally based, small and medium sized enterprises.

The stakes are extraordinarily high. An economy that routinely favors large over small firms and incumbent companies over new entrants is ultimately less competitive, innovative and inclusive. The Procurement Economy, in essence, must become an exercise in market making and business building. As we wrote months ago, “Put simply, we need a paradigm shift in public contracting, away from an individual agency’s short-term buying needs and toward contracting as a tool to promote regional market dynamism, sectoral innovation, and business- and wealth-building.”

To seize this moment, our organizations have spent the past two years jointly creating a new tool – a Procurement Playbook – and applying and testing it in two communities, first San Antonio and then El Paso. The results were the creation of two customized initiatives – Supply SA and Supply El Paso – that are now at different stages of implementation.

Our goals in both communities were threefold:

- to size the procurement economy in each community by assessing the scale of spending by federal, state and local governments;

- to capture the challenges facing local businesses, sourced through interviews with dozens of local firms, key governmental entities and local institutions and intermediaries; and

- to make a series of actionable recommendations designed to make the procurement system work better for small businesses and give local businesses the support they need to grow and scale.

The selection of the communities followed similar paths.

- Both cities were part of a pilot initiative, the Aspen City Action Lab, a market making endeavor to accelerate community wealth building in 6 cities with significant Latino populations.

- As part of the City Action Lab, both cities had formed local steering committees with representatives from local governments, business chambers, entrepreneurial support organizations, universities and other key intermediaries, which showed enormous interest in focusing intensely on the procurement economy.

- The Supply SA Procurement Playbook effort was launched In May 2022 with support from the San Antonio Area Foundation. The final Playbook was delivered to the community in November 2022.

- The Supply El Paso Procurement Playbook effort was launched in February 2023, with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. The final Playbook was delivered to the community in January 2024.

In both metros, our effort has been inspired and informed by a remarkable group of national and local leaders. This work was initiated by U.S. Representative Joaquin Castro who recognized from the outset the possibilities that federal investments would create for small businesses. His office had already conducted an early analysis of spending patterns across multiple local governments and agencies; Supply SA built on this foundation by providing a deeper assessment across a broader set of agencies.

The San Antonio and El Paso Playbooks have also been embraced and stewarded by public, private and civic leaders who have begun to practice a form of radical collaboration in the service of increasing the local share of public procurement.

Our objective has been to create a tool that every community and state in the nation can adapt and customize. To the greatest extent practicable, we have strived to use commonly available data with a purpose, revealing and humanizing procurement deficiencies in a way that can motivate action rather than resignation. We have also tried to invent and apply assessments of procurement practices that can be codified, routinized and drive reform.

Here is what we have found:

Large but Under-Performing Procurement Economies

The procurement economies in San Antonio and El Paso are large and growing. But public resources are not being used to their fullest extent to grow local and diverse-owned businesses. In many cases, public resources are supporting businesses located out of the metropolis or even the state, a leakage of business opportunity.

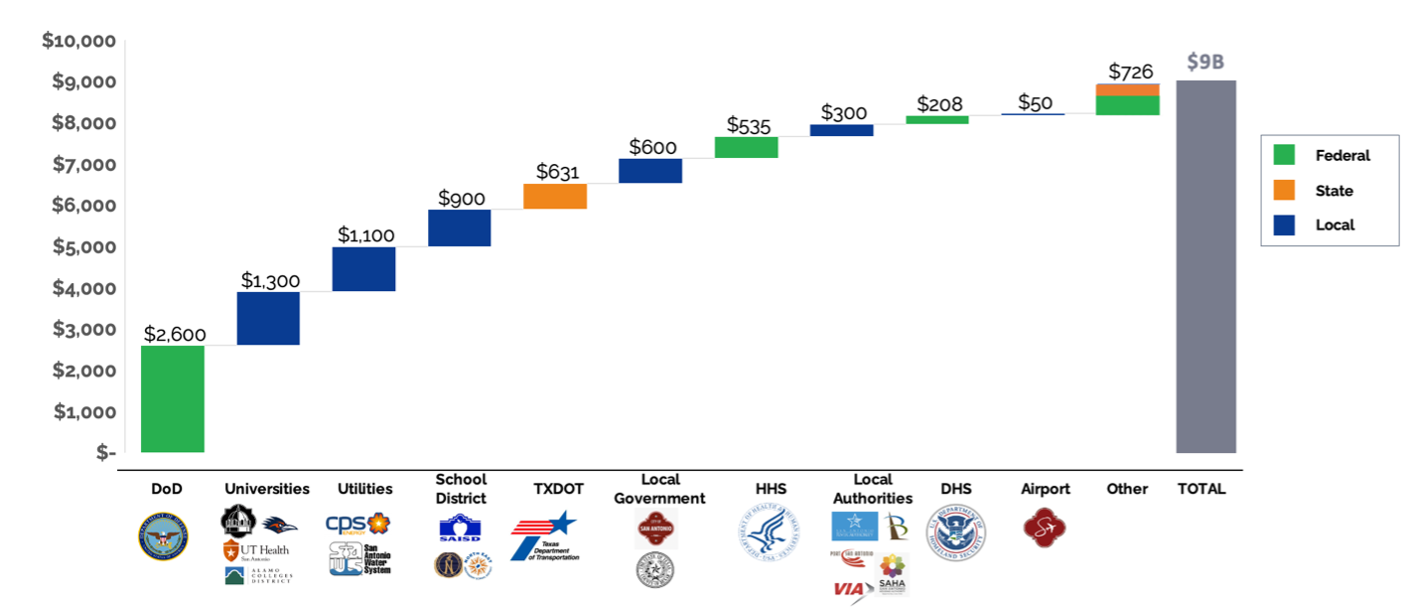

Supply SA assessed spending across a broad spectrum of federal, state and local agencies. The city is the 7th largest in the country with a population over 1.4M; the metropolis is the 24th largest. As a consequence, the procurement economy is super-sized. As the following chart shows, the city and county are receiving or bidding out contracts worth more than $9B annually. Federal agencies constitute $3.9 billion of this spending; the Department of Defense is the largest by far, with $2.6 billion in active contracts for FY 2021. Remarkably, we estimate that local entities procured $4.2 billion in contracts during the same fiscal year, including $1.1 billion from the electric and water utilities and over $600 million from the city and county governments.

Chart 1. Public Sector Procurement Spending in the San Antonio Region by Agency (in Millions of Dollars)

Notes: Universities spending was estimated value based on the three largest universities: Northside IDS, North East IDS, and SAISD. Airport spending was estimated value assuming procurement spending represented 35% of its operating spending during FY 2021 (~$129M). Federal contracts represent all active contracts in 2021. Considering just contracts that started in FY 2021, the federal government obligated/spent $2.7 billion.

To focus our analysis, we drilled down into the spending patterns of 13 separate local entities.[1] Here we found that only ~$500M out of the $3.3B spent by these agencies went to Latino- and Black-owned firms in FY 2021. This 15 percent of the total spend is far from being representative of San Antonio’s population (which in Bexar County is 60.7 percent Latino and 7.7 percent Black).

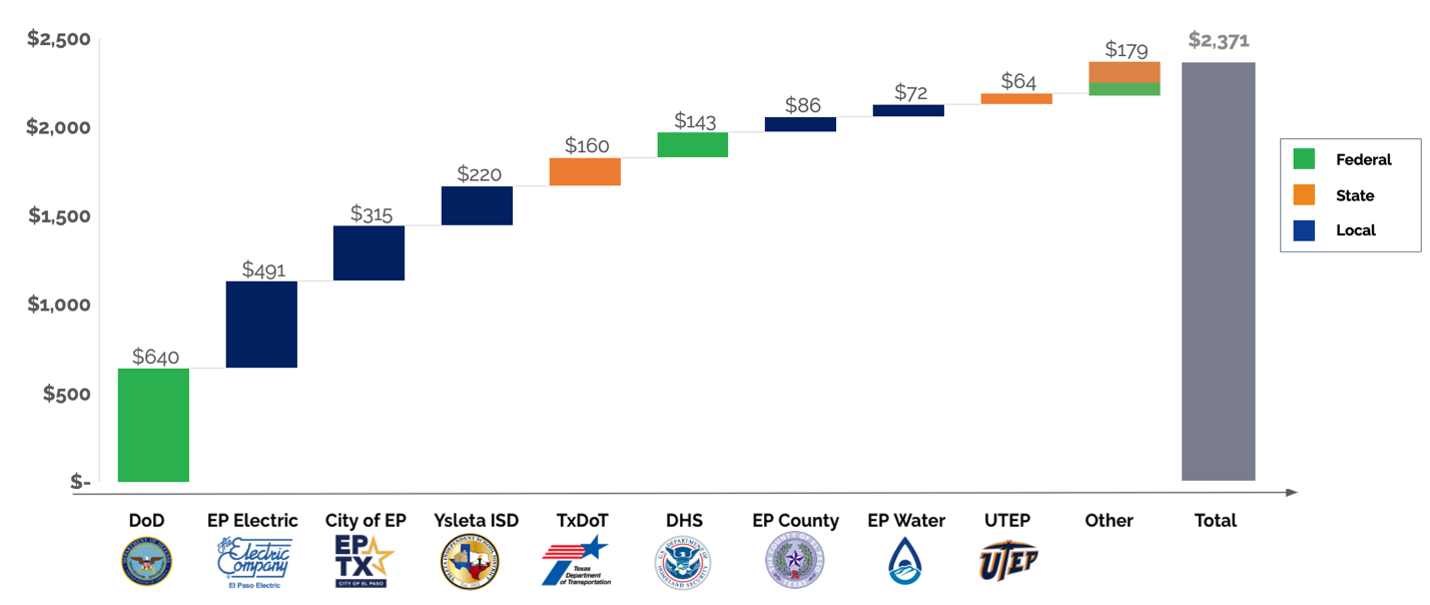

Like Supply SA, Supply El Paso assessed spending across multiple layers of government as well as the private electric utility, El Paso Electric. The city is the 23nd largest in the country with a population over 678,000; the metropolis is the 66th largest. As the following chart shows, the city and county are receiving or bidding out contracts worth more than $2.4 B annually.

Chart 2. Public Sector Procurement Spending in the El Paso Region by Agency (in Millions of Dollars)

Notes: Federal Data refers to the 5-year average of all new contracts awarded in the El Paso region. Local data is based on information shared by local agencies. State data was estimated using Texas Expenditures by County (non-procurement expenses were excluded: salaries, employee benefits, travel, leases, intergovernmental payments, claims, payment of interest, and lottery payments).

As the chart illustrates, the federal Department of Defense (“DOD”) is the leading public entity in spending in the region, injecting $640 million into El Paso County each year, much of which goes towards contracts to support operations and maintenance at Fort Bliss. However, these contracts predominantly go to firms outside of El Paso, despite the existence of local capacity for these contracts. Incredibly, only 3 out of every 10 dollars of direct federal spending goes to local firms, underscoring the fact that spending in the region frequently does not directly benefit the local economy.

EP Electric is the second largest buyer in the county, purchasing $491 million annually. As the energy transition proceeds, there will be ample opportunities to have local firms participate in multiple segments of green supply chains. As described below, we deconstructed the supply chain for EV charging stations, to understand where local firms might be best situated to take on different kinds of activity (manufacturing versus installing versus maintaining) in what is a rapidly growing sub-sector of the climate economy.

Common Barriers to Small Business Contracting

Our findings naturally drove us to look behind the numbers to understand the reasons why local and diverse small businesses were underperforming.

In San Antonio, our research involved engagement with multiple agencies through surveys and interviews. This led to a series of conclusions.

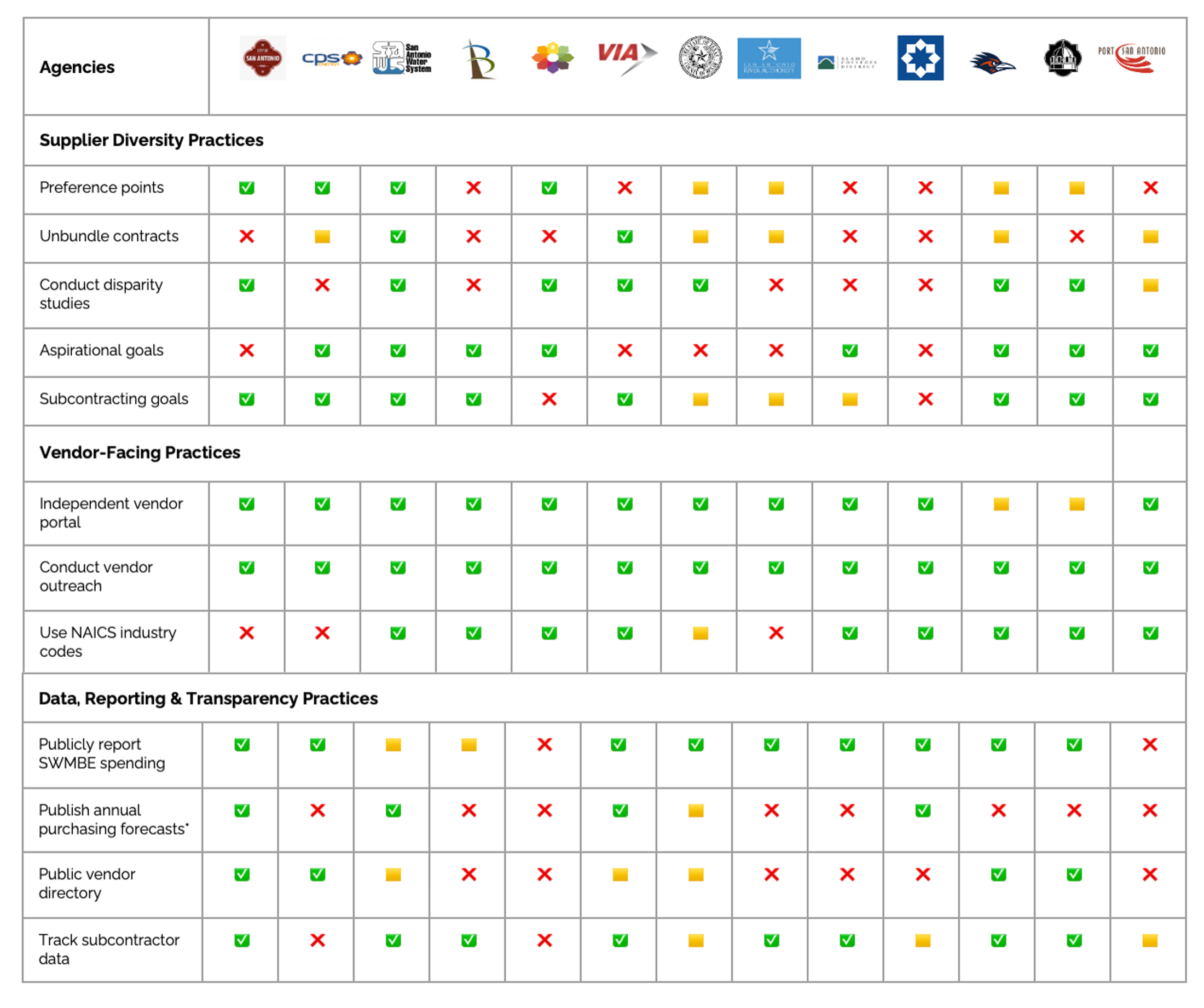

- The procurement economy is deeply fragmented, divided across multiple levels of government and separate agencies. The absence of a unified local procurement system leads to supplier confusion and difficulties in finding solicitations and submitting bids across various independent entities. More significantly, the extreme variance in agency practices, definitions and requirements, as seen in the chart below, impose enormous burdens on firms that have limited capacity to navigate complex systems.

Chart 3. Variability in Agency Practices Across 12 Dimensions: A Survey of 13 Agencies

Notes: Other practices we didn’t survey on are also ripe for collaborative reform and innovation: RFP language; bidder feedback, evaluation panel norms, cooperative purchasing, and bonding requirements.

Beyond fragmentation, our research in San Antonio found two other contributing factors.

- Supplier diversity is mostly treated as a compliance exercise, but growing firms require an economic development focus, in collaboration with the small business ecosystem. Just three of the 13 agencies we examined in San Antonio have a supplier development program focused on helping small firms secure larger contracts and use them to grow. This should be the norm rather than the exception.

- Suppliers do not have access to fit-to-purpose financial products that enable firms to access bonding and capital to grow staff, buy equipment, and take on larger contracts. Most capital products are tailored to large companies with strong financials and powerful networks.

In El Paso, we focused more intensely on interviewing and surveying dozens of local enterprises and engaging extensively with local stakeholders. Most of the firms we interviewed were deeply connected to the construction supply chain, offering a wide range of services, including architecture and engineering, construction contracting, and maintenance services. Moreover, most of these firms have 5-100 employees, $1M-$20M in annual sales revenue, and more than 10 years of operations. They are, in our parlance, ready to scale.

Our research reinforced the central finding in San Antonio, namely that fragmentation in public procurement, across multiple layers of government, is a major barrier to local and diverse firms capturing a higher share of public spending. But local businesses also identified other factors.

- In many cases, decisions around federal procurement are not made in El Paso, but in centralized purchasing offices located in other metropolitan areas. Sheer physical distance limits the ability of El Paso’s businesses to establish effective connections.

- Many local procurement offices lack the capacity to engage with local firms in ways that help them grow their ability to compete (e.g., by explaining why firms might have lost a particular bid).

- Fragmentation as well as these factors leads to a disjointed marketplace, where buyers and suppliers rarely interact in ways that strengthen mutual understanding and respect.

A Roadmap for Success

To address these challenges, our Playbooks recommended a series of institutional reforms designed to reduce fragmented processes and practices among buyers, build capacity and ease access to contracts among suppliers and drive a new kind of market making that builds wealth and strong local economies.

San Antonio has already started down the path towards systemic reform. There, Henry Cisneros, the former US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, was empowered by local elected officials, San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg and (then) Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolf to build a new kind of public-public partnership. (Notably, Peter Sakai, the new Bexar County Judge, has continued his support for this effort).

Here is how it works.

Cisneros convened the CEOs of fourteen local entities that were the prime subject of the Aspen/Nowak research. This cross governmental convening, most likely the first of its kind anywhere in the US, is designed to send a strong signal that the public sector is united around the central goal of using procurement to grow local, diverse firms.

A Procurement Innovation Council, composed of procurement officers and SWMBE specialists from the fourteen entities, small business advocacy organizations, and small business owners, has been tasked with the detailed work of reforming and harmonizing procurement practices across agencies, buttressing supplier development efforts across multiple stakeholders and exploring and deploying innovations in capital and bonding products.

To gauge progress, an Accountability Council composed of the Mayor, County Judge, Congressman Castro and State Rep. Barbara Gervin-Hawkins has been formed.

Significantly, change has not been confined to the public sector. Janie Barrera, the former President and CEO of the LiftFund, a community development financial institution, has been a major driver of Supply SA throughout. And the University of Texas San Antonio, with the support of U.S. Representative Castro, launched a Procurement Academy in September 2023; the first cohort of small businesses graduated in December 2023. The Academy critically helps small businesses navigate the procurement practices and requirements of state, local and federal agencies. When it comes to procurement, the devil is truly in the details.

The recommendations in El Paso build on the San Antonio progress but are customized to the distinctive business growth opportunities in that metropolis.

As in San Antonio, Supply El Paso calls for a new collaboration -- a Procurement Marketplace Council -- led by the city and county government that would involve key procurement agencies as well as critical parts of the business ecosystem like chambers of commerce and business leadership groups.

The goal, generally, is to bridge the gaps between procurement opportunities, support organizations and regional vendors and foster the creation of a robust marketplace for local firms. Given the oversized procurement power of the defense and energy sectors, Supply El Paso recommended that the initial priorities be around two areas of opportunity, one around Defense Procurement, the other around green supply chains. Significantly, the University of Texas El Paso, with the strong backing of U.S. Representative Veronica Escobar, has already won several federal awards to advance defense related manufacturing and procurement.

As of the writing of this newsletter, Mayor Oscar Lesser and County Judge Ricardo Samaniego, along with their excellent teams, are determining how to implement a new collaborative approach to procurement. Critical partners include the El Paso Hispanic Chamber, the El Paso Chamber, El Paso Electric, the Borderplex Alliance, WestStar Bank, the Hunt Institute at the University of Texas El Paso and the local Apex Accelerator and Small Business Development Center. Business building, in other words, takes an ecosystem.

Conclusion

The launch of Supply SA and Supply El Paso, and the invention of Procurement Playbooks more broadly, could represent a new chapter in the decades long goal to use the buying power of governments to grow local, diverse businesses.

This new chapter recognizes that metropolitan areas are not only the engines of our economy but are also powerful local networks of governments, universities, chambers of commerce, financial institutions and entrepreneurial support organizations. These local ecosystems, if fully aligned and unleashed, offer the best chance we have to grow strong small businesses and prosperous local economies.

Both San Antonio and El Paso are “collectively using their economic power to shape markets, alter business and philanthropic practices, and catalyze new forms of innovative finance,” the aspiration articulated in The Metropolitan Revolution over a decade ago.

We fundamentally believe that every metropolitan area has the wherewithal to design and deliver Procurement Playbooks. Future newsletters will focus on diagnostic breakthroughs that, in our opinion, can be easily spread and scaled throughout the country. Yet diagnostics, no matter how revelatory, are not sufficient to drive change. That will take leadership like the kind we have seen in San Antonio and are witnessing in El Paso. These leaders understand full well what is at stake. The industrial and energy transitions, catalyzed by large public and private spending, are here to stay. Whether small businesses will be part of those transitions and the wealth that they will engender will depend on local and metropolitan organizing and purpose. That, in the end, is the secret to unlocking the Procurement Economy.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Domenika Lynch is the Executive Director of the Latinos and Society Program at the Aspen Institute. Victoria Orozco is the Founder of the Punto Lab. Milena Dovali is a Research Officer and Benjamin Weiser is a Research Analyst at the Nowak Lab.

[1] The 13 agencies included the City of San Antonio, Bexar County, CPS Energy, San Antonio Water System, University Health, Brooks, VIA Metropolitan Transit, Opportunity Home San Antonio, the San Antonio River Authority, Port San Antonio, Alamo Colleges District, University of Texas San Antonio, and Texas A&M San Antonio, Since the creation of this report, UT Health Science Center joined the effort.