The Complex Capital Stacks of Re-Industrialization

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

December 19, 2024

As we have written before, the U.S. is witnessing a period of rapid re-industrialization.

Perhaps no industry is more prominent in the United States’ nascent industrial resurgence than semiconductor manufacturing. Semiconductors are ubiquitous, powering everything from consumer electronics to advanced industry. They are also central to national security, earning a place on the Department of Defense’s list of Critical Technology Areas.

Despite leading the world in the design and production of semiconductors in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. share of global semiconductor production declined precipitously, falling to approximately 40% by 1990 and 10% by 2020, with most production now taking place in East Asia.

To address geopolitical and economic vulnerabilities related to semiconductor supply chains, Congress passed the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) Act with bipartisan support in 2022. The legislation aimed to bolster U.S. capabilities in semiconductor design and production through a mix of industrial incentives and investments in research and development. CHIPS appropriations included:

-

$39 billion for semiconductor production incentives, including $6 billion in credit supports for up to $75 billion in loans;

-

$13 billion for semiconductor research and development (including $11 billion through the Department of Commerce and $2 billion through the Department of Defense); and

-

$200 million for microelectronics-related workforce development and education activities.

The legislation also included a 25% investment tax credit for the domestic production of semiconductors and related equipment.

Since the passage of the CHIPS Act, the U.S. has seen announcements of new or increased investments to the tune of tens of billions of dollars in semiconductor production facilities, or fabs, like Intel’s $28 billion in Ohio, Micron’s $100 billion in New York, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation’s (TSMC) $65 billion in Arizona, among others.

While CHIPS-funded subsidies feature prominently in project announcements, a closer look at their full capital stacks reveals a far richer picture. Far from being centrally planned and government-led, semiconductor fab and related investments are market driven. Federal funds represent a relatively small share of total capital stacks, but have been pivotal in catalyzing private, state, and local resources.

The large-scale investments of three of the largest players in the industry – TSMC in Arizona; Intel across four states; and Micron in New York – demonstrate the diverse set of actors and complex capital stacks enabling re-industrialization.

Capital Stack Elements

We examined these investments across four key areas: the semiconductor fabs themselves, supportive infrastructure, workforce development, and research and development. Our analysis demonstrates complex and distinct capital stacks across each dimension.

Fabs: Semiconductor fabs demand substantial capital investment and require regular upgrades to stay aligned with the latest technological advancements. Reshoring semiconductor fabs back to the U.S. is made possible by a mix of corporate balance sheets, access to capital markets, and public funding in the form of grants, loans, and tax incentives.

Infrastructure: Chip production is a complex process that demands vast amounts of land, water, and energy to meet the stringent requirements of manufacturing. Many of these fabs sit on greenfield sites in remote areas, which require extensive infrastructure upgrades across transportation, utilities, energy grids, and water supply. Local governments take an active role in facilitating infrastructure upgrades to attract and support large-scale private investment.

Workforce: Recruitment and retention of a skilled workforce has emerged as a major challenge for expanded domestic chip production. With a shortage of qualified labor, projects have encountered delays at various stages, leading to disrupted timelines. Building a sustainable workforce, both for the short and long term, remains critical to the success of semiconductor reshoring. Local and federal governments, along with their partners, are now exploring multiple approaches to tackle this challenge.

On the federal level, each direct funding from the CHIPS and Science Act includes a component dedicated for workforce development. Additionally, the Biden-Harris Administration’s Workforce Hub initiative aims to support the rapidly expanding semiconductor and advanced manufacturing ecosystems across regions, with Arizona, Ohio, and New York selected for participation.

On the local level, governments form partnerships with private and public players to direct funds into various workforce development programs. Local governments also work with universities and community colleges to boost the talent pipeline for engineering technology programs and advanced manufacturing credentials.

Research and Development: Securing a front-runner position in the semiconductor industry demands not only enhancement of mass production capabilities but also continuous innovation to bolster overall supply chain resilience.

On the federal level, the Department of Defense supports activities of eight Microelectronics Commons Hubs through the CHIPS for America Defense Fund, including the Southwest Advanced Prototyping Hub in Arizona, The Midwest Microelectronics Consortium in Ohio, and the Northeast Regional Defense Technology Hub in New York. The goal of the Microelectronics Commons Hub is to unite the expertise of private companies and academic institutions to move ideas from lab-to-fab, drive prototyping and scale production capabilities.

State and local actors bolster R&D efforts by partnering with surrounding universities to fund and establish research centers. These efforts aim to enhance R&D capabilities while benefiting from the strategic advantage of proximity to growing semiconductor ecosystems nearby. This closeness allows greater collaboration, access to resources, and alignment with industry needs, further strengthening local innovation and competitiveness in the semiconductor space.

Supply chain ecosystem: A true industrial resurgence in semiconductor manufacturing demands the presence of integrated upstream and downstream producers. This complete industrial ecosystem stands as a critical foundation for the US to establish and maintain leadership in the semiconductor sector across all fronts. Improving resilience against supply chain disruption and expanding domestic production requires localizing semiconductor supply chains. Efforts to strengthen and co-locate supply chains with fabs include supplier consortia and site readiness funds, among others.

Deal by Deal Perspective

TSMC in Arizona:

TSMC’s greenfield project to build three fabs in Phoenix, Arizona is made possible by more than $90 billion in total private and public capital. TSMC’s own balance sheet provides the lion’s share at $65 billion, supplemented by $6.6 billion in direct funding from the CHIPS and Science Act; $5 billion in proposed loans from the CHIPS Program Office; and advanced manufacturing investment tax credits of up to $16 billion, contingent on capital expenditure eligibility determination by Department of Treasury and the IRS.

Figure 1: TSMC Arizona Capital Stack for Fabs

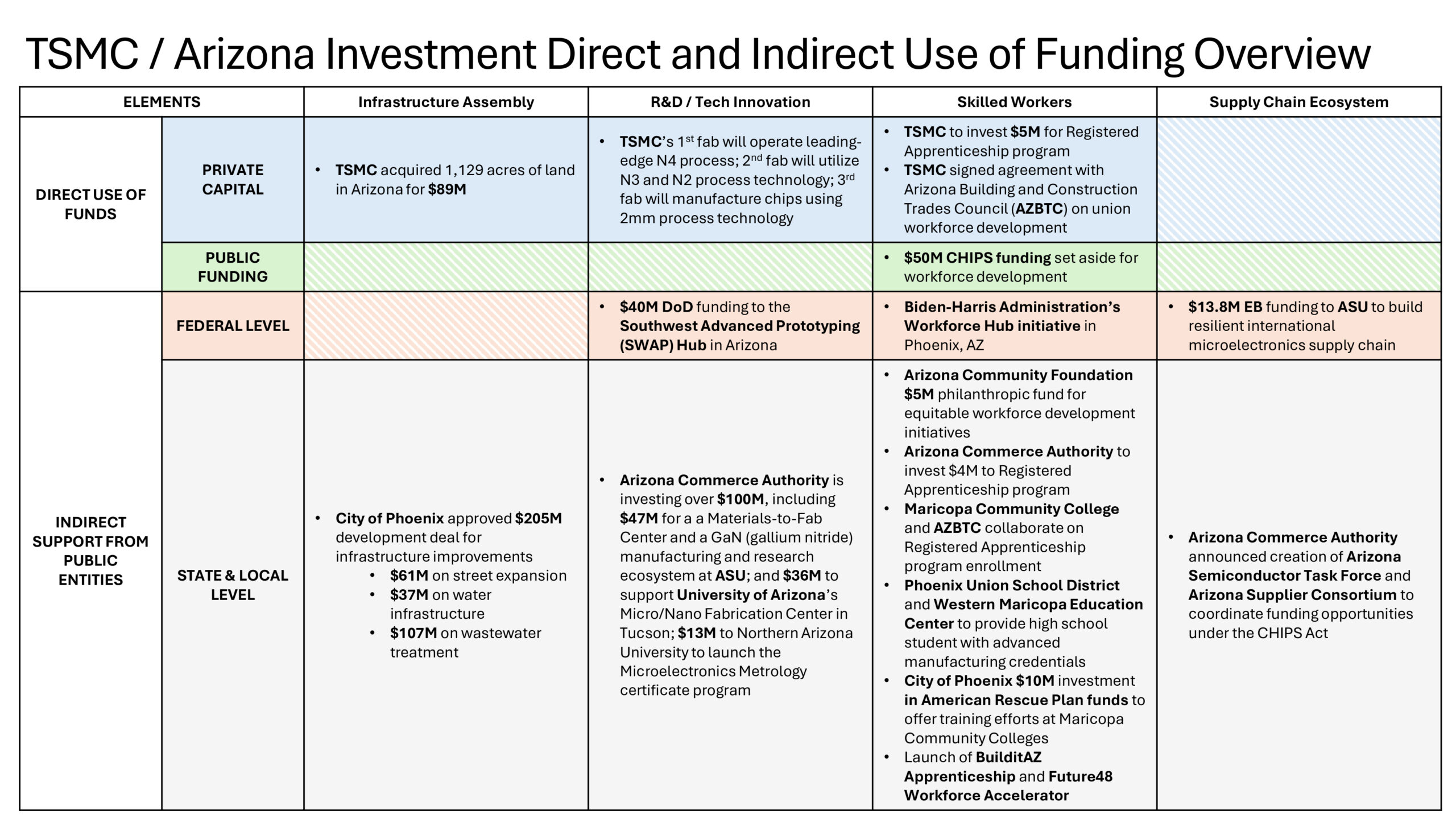

To develop the necessary infrastructure supporting the campus, the city of Phoenix approved a $205 million development deal for infrastructure improvements, including $61 million for streets, $37 million for water, and $107 million for wastewater.

A host of public and private entities are likewise aligning efforts to ensure a steady stream of skilled workers. TSMC itself has committed $5 million for a registered apprenticeship program and partnered with the Arizona Building and Construction Trades Council for the construction of new facilities. Additionally, $50 million of its CHIPS grant funds are earmarked for workforce development efforts.

At the state and local levels, workforce development initiatives include $5 million from the Arizona Community Foundation, $4 million from the Arizona Commerce Authority, and $10 million of American Rescue Plan Act funds from the City of Phoenix to support training efforts at Maricopa Community College.

Arizona is also at the forefront of R&D efforts related to chip design. Arizona’s investment in R&D includes $270 million for Arizona State University’s Materials-to-Fab Center (including $30 million from the Arizona Commerce Authority, $17 million from ASU, and $200 million from Applied Materials), $36 million for the University of Arizona’s Micro-Nano Fabrication Center in Tucson, and $13 million for Northern Arizona University’s new microelectronics metrology certificate program. Arizona has also received $40 million for the Southwest Advanced Prototyping Hub through the Department of Defense’s Microelectronics Commons Hubs program.

To enhance the development of the state’s semiconductor ecosystem, the Arizona Commerce Authority has announced the formation of the Arizona Semiconductor Task Force and the Arizona Supplier Consortium. These initiatives aim to coordinate funding opportunities provided under the CHIPS Act. The task force includes key supply chain operators specializing in materials, equipment, R&D, and packaging, designed to support the manufacturing operations of TSMC and Intel in Arizona.

Figure 2: TSMC Arizona use of funds for infrastructure and supportive investments

Intel in Arizona, Ohio, New Mexico, and Oregon:

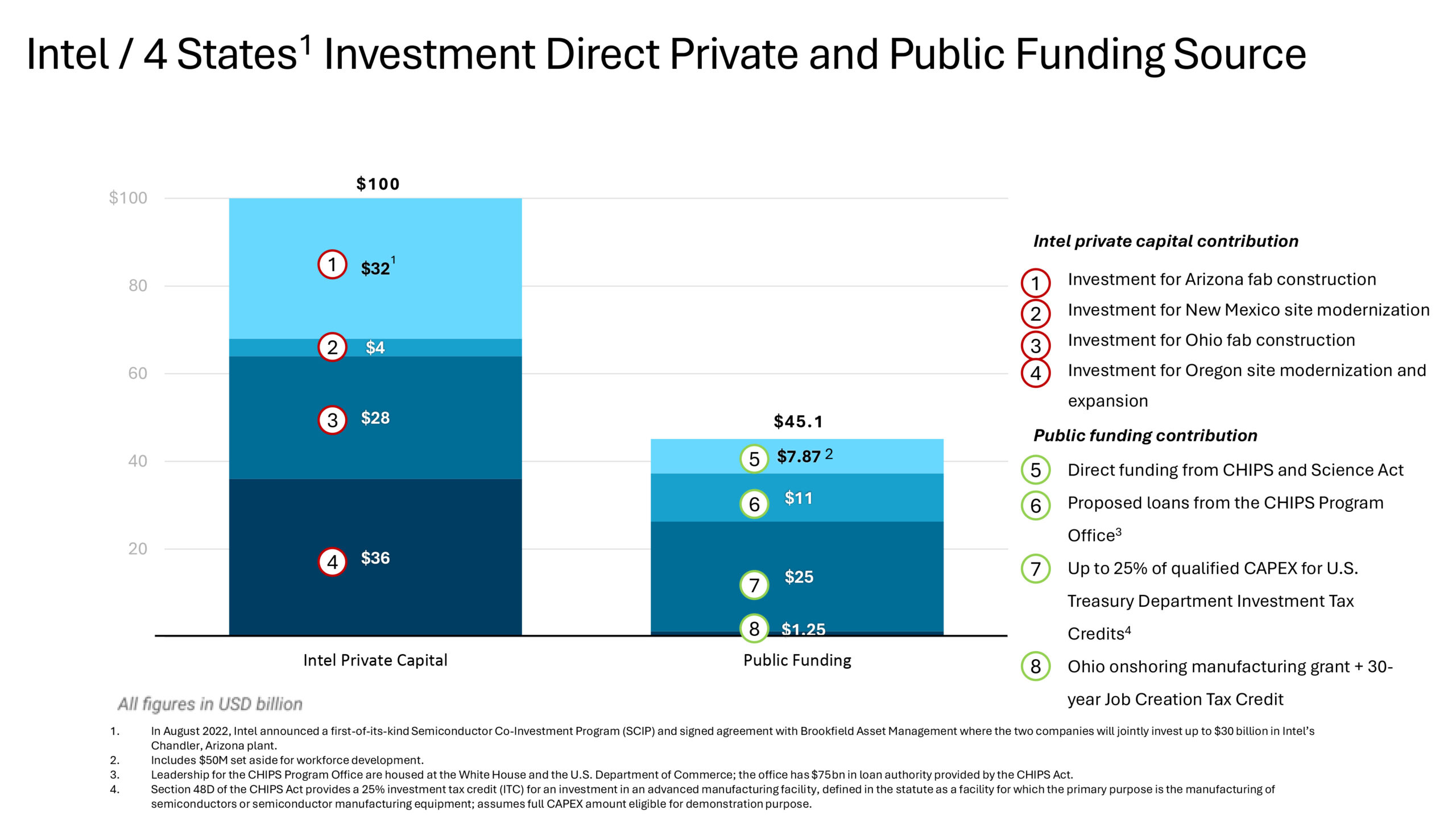

Intel’s proposed $100 billion investment includes construction of fabs in Chandler, Arizona, and New Albany, Ohio, alongside the modernization and expansion of existing facilities in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, and Hillsboro, Oregon. Intel’s project is funded through a mix of profit reinvestment and capital markets. Notably, Intel’s Arizona fabs are part of the Semiconductor Co-Investment Program (SCIP) with Brookfield Asset Management, with both companies jointly committing up to $30 billion. On the public side, Intel stands to receive nearly $8 billion in direct funding from the CHIPS and Science Act, $11 billion in proposed loans from the CHIPS Program Office, and up to $25 billion in advanced manufacturing investment tax credits, contingent on IRS eligibility determinations. Additionally, subsidies from the state of Ohio exceed $1.2 billion, including a $600 million grant and a 30-year Job Creation Tax Credit potentially saving Intel up to $650 million.

Figure 3: Intel Capital Stack for Fabs

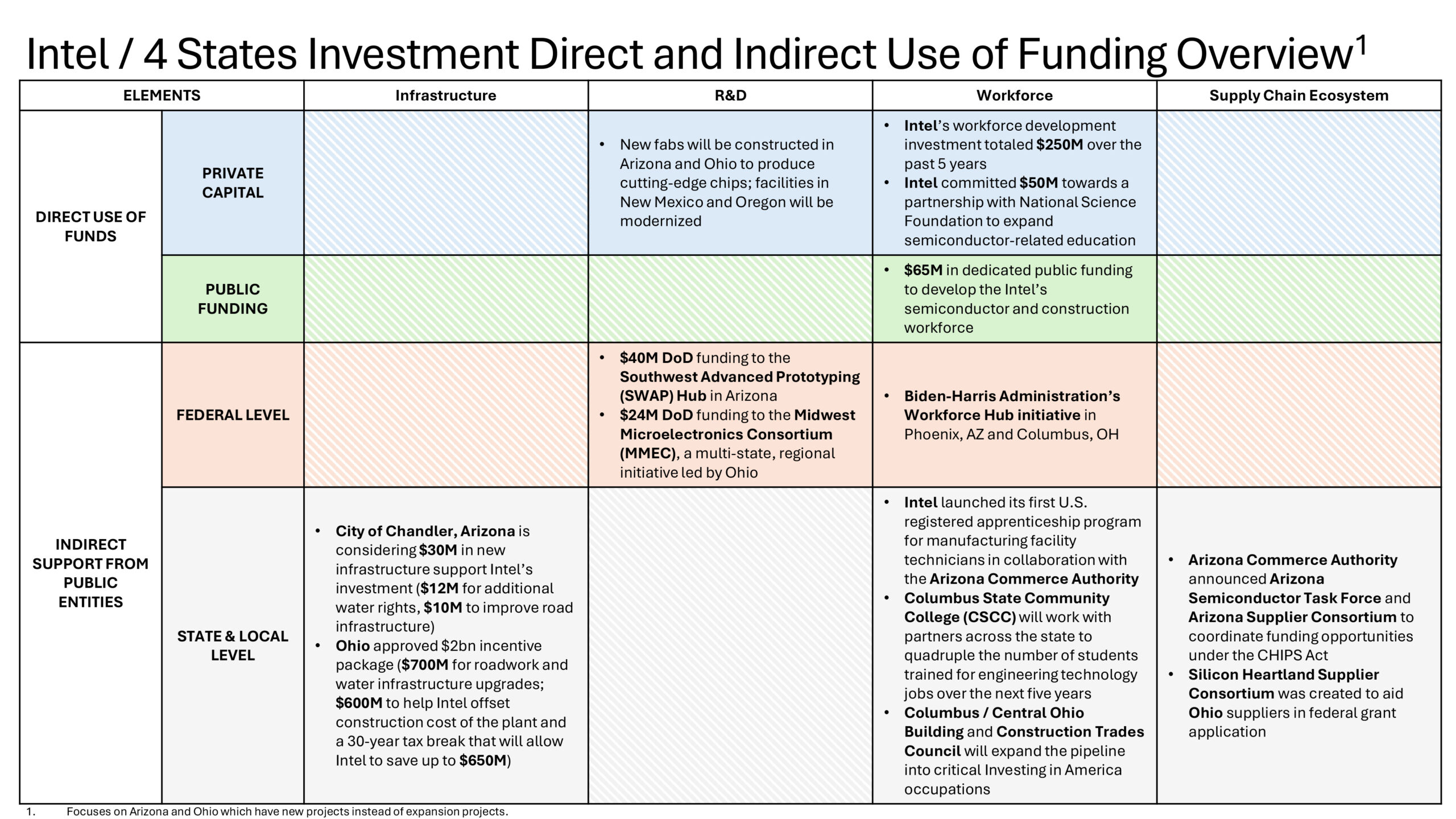

For infrastructure, the city of Chandler is supporting a $30 million package including $12 million for water and $10 million for roads. In Ohio, the state approved a substantial incentive package for Intel, with $700 million allocated for roadwork and water infrastructure improvements.

Like TSMC, Intel’s investments in Arizona and Ohio will both benefit from the federal Workforce Hub initiative. The Phoenix hub focuses on semiconductor and materials manufacturing, with American Rescue Plan funds to support workforce programs for Tribal and Hispanic communities through childcare services and training centers. The Columbus hub focuses on diverse sectors like semiconductors, clean energy, and transportation, with a two-year semiconductor education program across twenty community colleges and an innovative Registered Apprenticeships program in place. In greater Columbus, Intel will partner with Columbus State Community College to quadruple the number of engineering technology graduates within the next five years, and the Central Ohio Building and Construction Trades Council will support construction-related jobs.

Department of Defense funding plays a critical role in regional R&D efforts surrounding Intel’s Ohio and Arizona plants. DOD awarded $24 million to the Midwest Microelectronics Consortium, along with the aforementioned $40 million to the Southwest Advanced Prototyping Hub in Arizona. These public-private consortia include hundreds of members across industry, academia, and government and aim to accelerate innovation in semiconductor design, testing, and production.

To enhance the supply chain ecosystem, the Silicon Heartland Supplier Consortium, which partners with Intel, JobsOhio, and the Ohio Grants Alliance, was established to help current and future Ohio suppliers compete for new federal grant funding for semiconductor materials and manufacturing equipment.

Figure 4: Intel use of funds for infrastructure and supportive investments

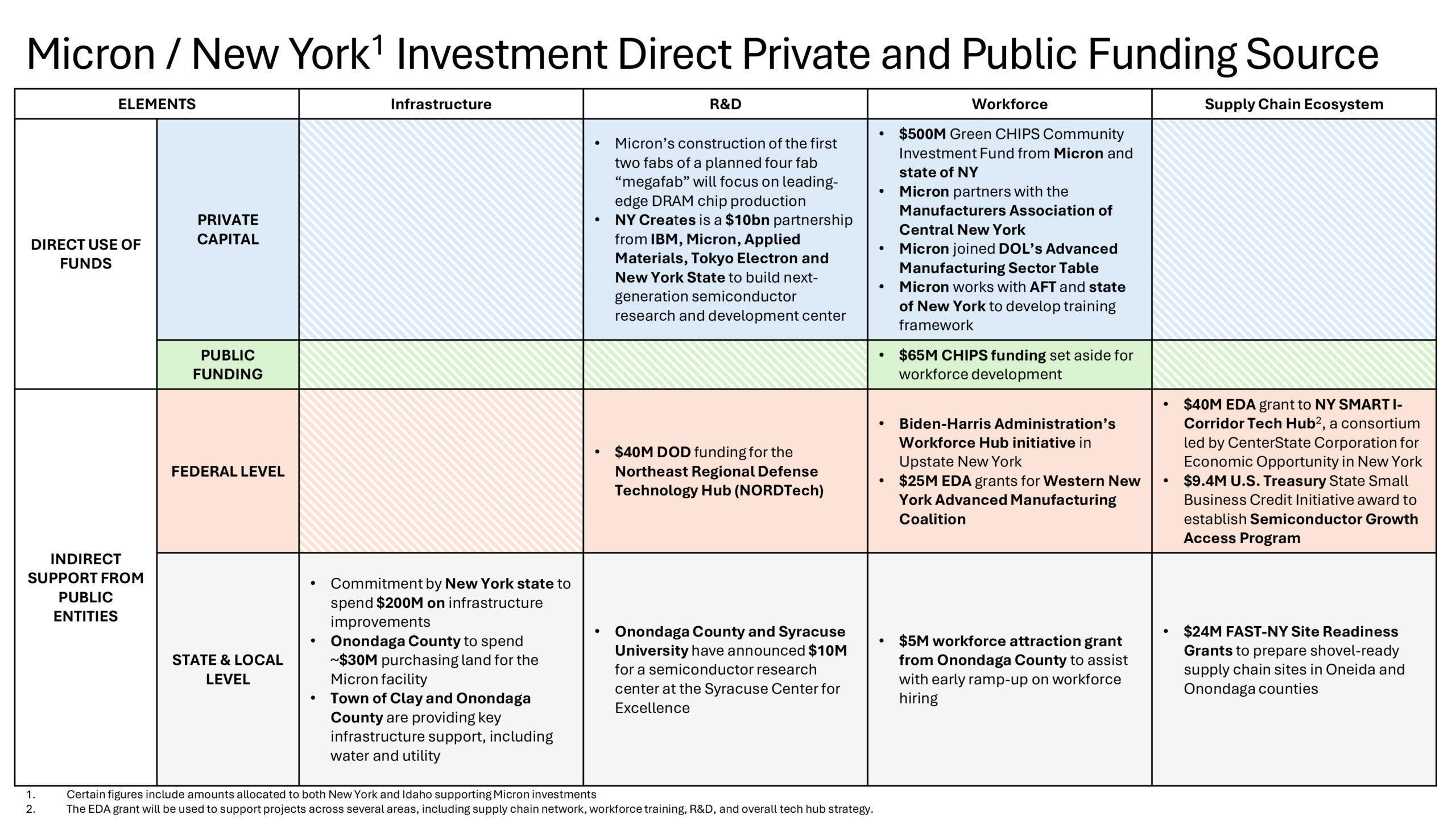

Micron in New York and Idaho:

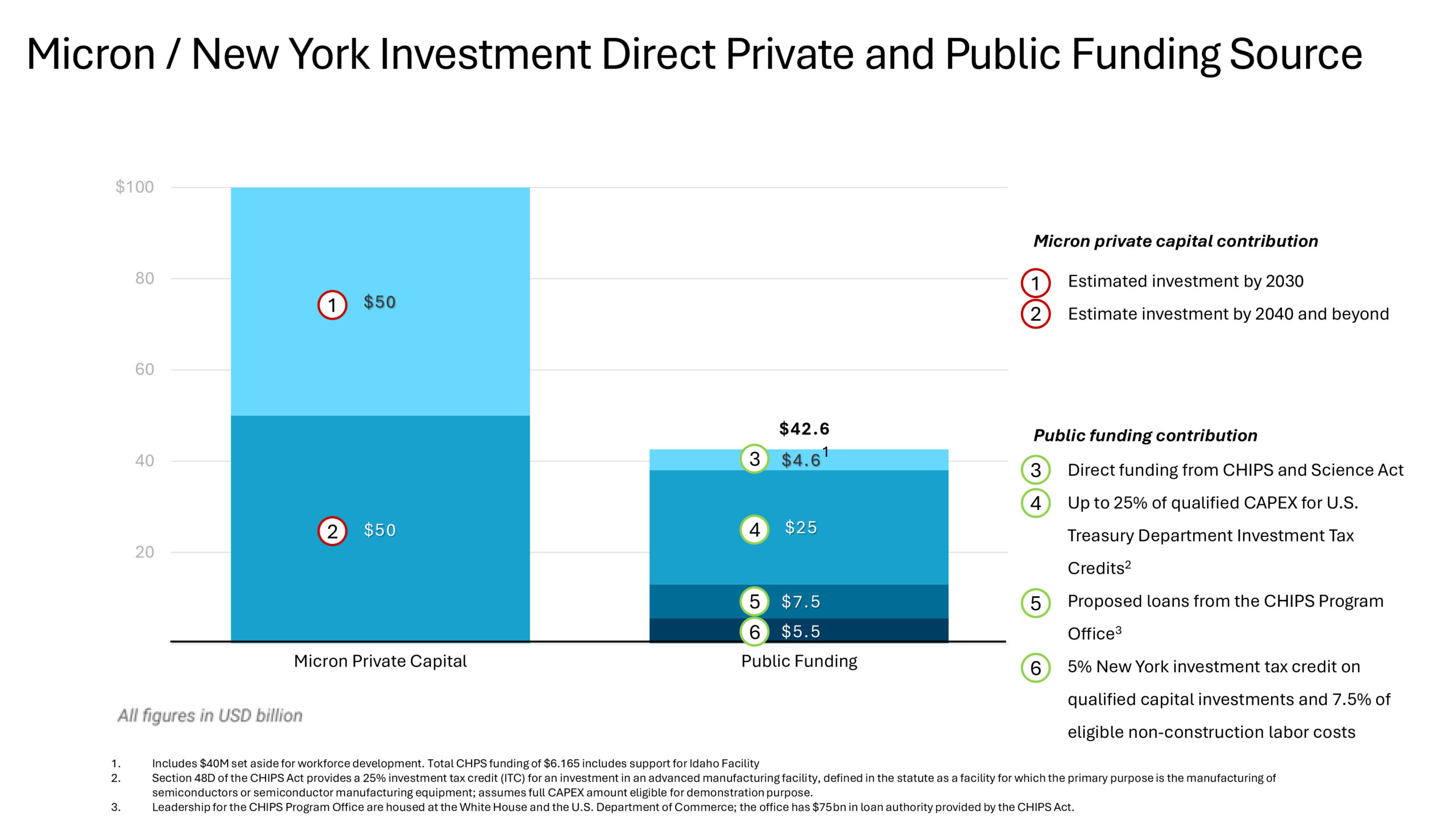

Micron’s $100 billion investment to create a four-fab manufacturing complex in Clay, New York, and an additional $25 billion investment to expand existing facilities in Boise, Idaho, draw largely from its own balance sheet. This is supplemented by $6.14 billion in direct funding from the CHIPS and Science Act (of which an estimated $4.6 billion is allocated for New York), $7.5 billion in proposed loans from the CHIPS Program Office, and up to $25 billion in advanced manufacturing investment tax credits, subject to eligibility determination. Additionally, the State of New York offers a 5% investment tax credit on qualified capital investments and 7.5% on eligible non-construction labor costs, potentially saving Micron up to $5.5 billion.

Figure 5: Micron Capital Stack for Fabs

For infrastructure upgrades, the state of New York, with support from Onondaga County, has committed $200 million, along with $30 million for land purchases, among other investments.

The region’s workforce development efforts are wide-ranging, including a $500 million public-private Green CHIPS Community Investment Fund, $65 million in CHIPS workforce development funding allocated across New York and Idaho via the Central New York Community Foundation, and $5 million from Onondaga County for early staffing efforts. These public and private funds help to scale up and deliver workforce innovations seeded by flexible philanthropic funding, such as CenterState CEO’s Work Train initiative. The region’s workforce development initiatives build on long-standing partnerships with K-12, adult education, and higher education providers like Syracuse University and Onondaga Community College.

Public and private actors have also announced a host of initiatives to keep the region at the leading edge of research and development. A $10 billion NY Creates partnership among IBM, Micron, Applied Materials, Tokyo Electron, and New York state will support a next-generation semiconductor R&D center. Like Arizona and Ohio, New York also received DOD support for the Northeast Regional Defense Technology Hub (NORDTech).

The state is also home to several efforts to bolster regional supply chains. New York’s $40 million EDA grant for the NY SMART I-Corridor Tech Hub seeks to integrate supply chain coordination, workforce development, and R&D capabilities to foster a vibrant, entrepreneurial, and innovative semiconductor ecosystem. It has leveraged the state’s FAST-NY site readiness grant program to prepare supply chain sites in Onondaga and Oneida Counties. New York was also awarded $9.4 million through the U.S. Department of Treasury’s State Small Business Credit Initiative to expand access to semiconductor supply chains for small businesses through the Investing in America Small Business Opportunity Program.

Figure 6: Micron use of funds for infrastructure and supportive investments

Lessons Learned and Unanswered Questions

Understanding the complexity and scope of these projects is an early but critical step to routinize and scale them.

While CHIPS subsidies have featured prominently in announcements of new semiconductor facilities, they represent relatively small pieces of the overall investments and are insufficient on their own to catalyze the resurgence of a domestic semiconductor industry. Rather, as this analysis demonstrates, these projects are made possible by intricate, layered, and messy capital stacks of which federal grants are just one part.

They also reveal the complexity of the U.S. economy. While the federal government can set the framework for re-industrialization, it takes diverse and coordinated networks across sectors and levels of government to make it happen.

This work also raises several questions:

-

Can we do this? Re-industrialization in an economy as complex as ours is proving to be no easy task. Even with the focused efforts of dozens of stakeholder groups and ample resources from the public and private sectors, these semiconductor projects still face headwinds. In most cases, they remain months or years away from initial production, let alone full-capacity operation. They face major construction delays, hiring slowdowns, and cost overruns. And semiconductors are only one piece of the broader trend towards reindustrialization. Major investments in electric vehicles, batteries, clean energy, and critical defense sectors are happening as well. The true test of re-industrialization’s sustainability will be whether the country can overcome these growing pains.

-

Can we empower and resource the right actors to make projects like these more efficient? Given the complex networks and capital stacks behind these projects, there is a clear need for nimble but well-resourced entities to coordinate efforts. Commerce’s CHIPS for America office has proven capable so far at the federal level. State and regional actors like the Arizona Commerce Authority, the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, Jobs Ohio, Columbus Partnership, Empire State Development and CenterState CEO in New York are key to braiding and blending diverse sources of capital from public, private, and philanthropic providers and developing lasting regional partnerships to maximize the impact of private investments.

-

Can we develop and sustain the necessary infrastructure – both social and physical – to support re-industrialization?

-

Housing – these facilities require thousands of workers in construction and thousands more in permanent production positions. Amid a national housing crisis, can we produce sufficient and accessible supply of housing to accommodate them all?

-

Transportation – given their natural resource intensity (i.e., land and water), these facilities tend to be located far from urban centers and their workforces. Can we develop effective, efficient, and well-coordinated transportation strategies to move people between homes and industrial centers?

-

Care economy – once operational, semiconductor facilities must operate around the clock, increasing demand for child and elder care as well as healthcare facilities. While CHIPS funds have included carrots for childcare funding, far more will be necessary. Can we address the national shortage of care facilities and providers to support an industrial transition of major proportions?

With an imminent transition to Republican control of the White House and Congress, major legislative and regulatory accomplishments of the Biden administration appear vulnerable to repeals and recissions. Republicans have already signaled their intention to cut back support for CHIPS “add-ons” like childcare and project labor agreements. But at its core, early outcomes from CHIPS-backed projects are consistent with bipartisan objectives, like the limited use of federal funds to catalyze state, local, and private market activity; derisking with China; and restoring U.S. industrial might to bolster national and economic security. The reshoring of critical production sectors of the economy will continue, and understanding the complex capital stacks of these efforts will be more important than ever.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Chloe Chai was a Graduate Research Analyst at the Nowak Lab in the summer and fall of 2024, and Bryan Fike is a Research Officer at the Lab