Archives, Ambivalence, and Dr. Clifford's Conference Paper

by Ava Purkiss, Ph.D

Posted on

August 5, 2025

Last summer, I was fortunate to conduct research at the Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections, housed within the Drexel University College of Medicine, as the 2024 M. Louise Carpenter Gloeckner Research Fellow. My research at the Center supported my current book project on the intersection of race and modern reproductive medicine. My work examines how Black women have shaped the field of gynecology as pundits, patients, and practitioners since the field’s inception in the mid-nineteenth century.

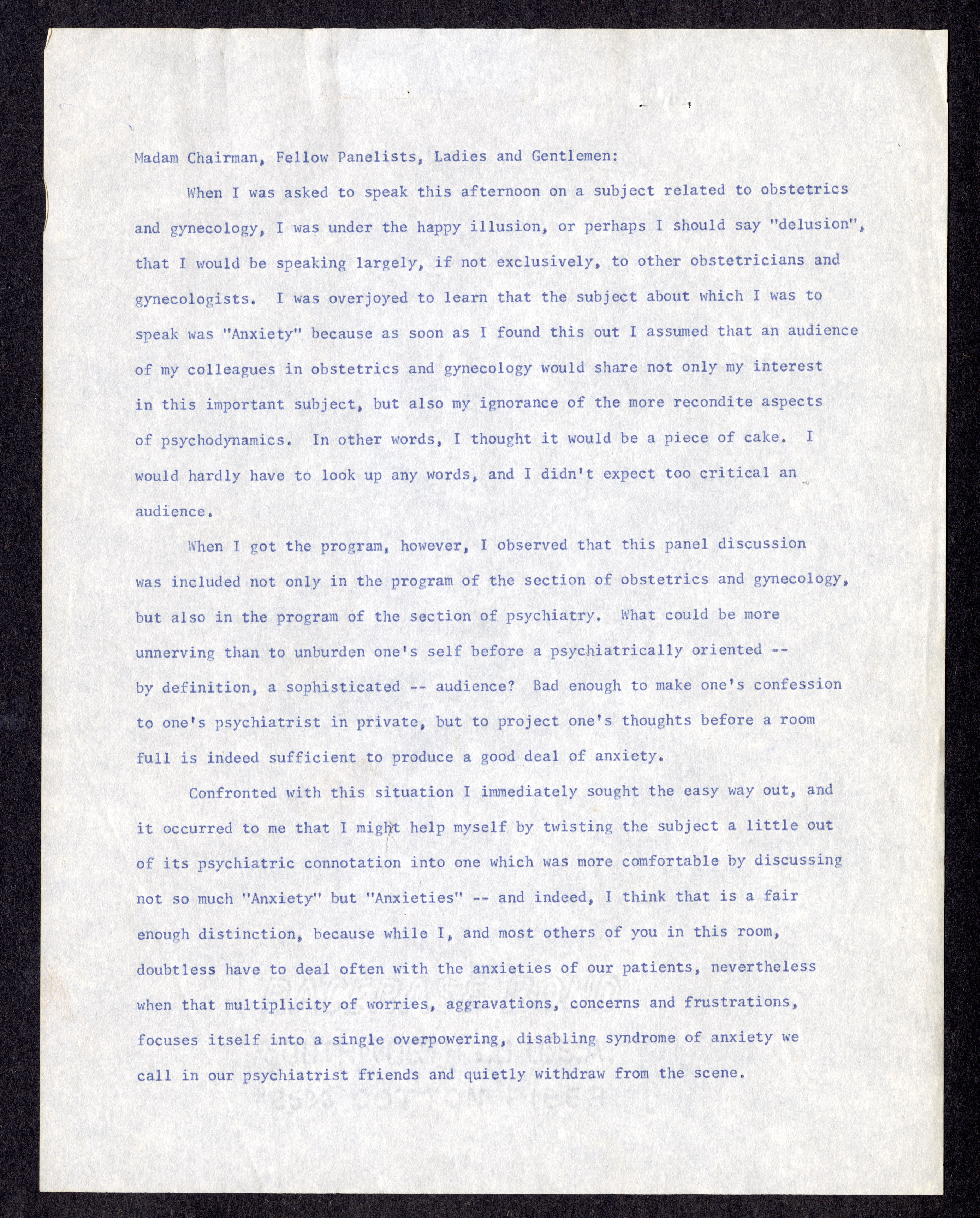

While my research at the Center focused on Black women in medicine, I also thought it prudent to examine the records of Black male physicians. When I encountered a conference paper by Black OB-GYN Maurice Clifford on anxiety and the practice of obstetrics and gynecology, I didn’t know what to think. Delivered in Chicago in August 1967 at the National Medical Association annual meeting (a Black medical professional organization), Clifford explored the emotional and psychological aspects of delivering reproductive care, speaking to the “psychodynamics” of gynecology. Clifford’s audience included the Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology sections of the NMA.

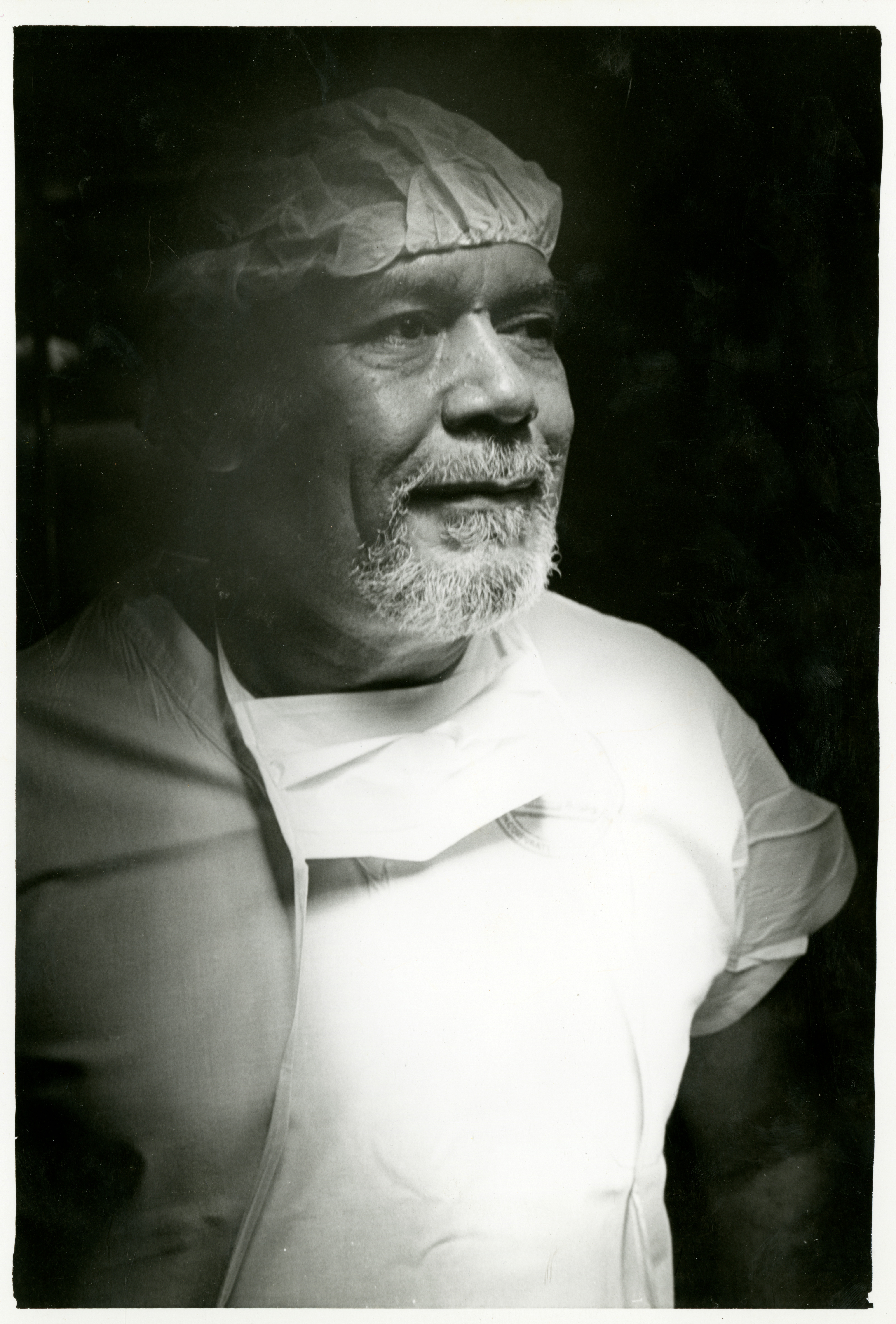

I knew little about Dr. Clifford when I happened upon his collection, except for some basic background information. Clifford earned his medical degree from Meharry Medical College, joined the Woman’s Medical College as a faculty member in 1955 (renamed the Medical College of Pennsylvania after becoming co-ed in 1970), was elected President of the College in 1980, and became the Commissioner of Public Health for the City of Philadelphia in 1986. He died in 2002 and was clearly beloved by his family, community, and professional circles. A photograph of him, shown to me by an archivist at the Legacy Center, portrayed a skilled, dignified, and kind medical practitioner (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Maurice Clifford, M.D., undated. From Accession 78, Public Relations files, box 84.

With this scant biography, I zeroed in on the topic and title of the conference paper, “Anxiety: A View Point of the OB/GYN.” Noting the talk concerned the psychological underpinnings of women’s physical ailments, I approached the document with some reasonable skepticism, understanding that notions of feminized emotional instability and “hysteria” had long served as justifications for women’s dismissal, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment. As a feminist historian, I also understood that numerous “medical men” had forged a centuries-old campaign to assert themselves as the foremost experts of women’s health, and women writ large. However, I had hoped that my skepticism would be unfounded and that Dr. Clifford, a rarity as a Black OB-GYN in the 1960s, would emerge as a champion of his female patients. Moreover, since I couldn’t be sure these attitudes reflected Dr. Clifford’s philosophy of medicine, I read the document ambivalently, giving Clifford the benefit of the doubt (which also constitutes a feminist approach).1

"The phenomenon of dysmenorrhea, is, in my view, largely an expression of anxiety. All of you are aware that dysmenorrhea runs in families. Older women teach girls at menarche that menstruation, which after childbearing is the most dramatic evidence of femininity, is painful. To those who are cursed with dysmenorrhea [,] it is part of the burden of womanhood, the lot of suffering women must bear in a man’s world. That there is a certain degree of physiologic discomfort in menstruation, and that there exists a significant pathologic causes [sic] for dysmenorrhea, is no less certain than that disabling dysmenorrhea, in most instances, is an emotional disorder [.] I believe this, although I treat primary dysmenorrhea in my practice on a physiologic basis—with anodynes and at times by ovulatory suppression. To a degree, this is not medicine but necromancy. The pills I prescribe constitute a professional acknowledgment of my patient’s ailment, and having established her feminine right to pain, my patient graciously allows me to relieve it."2

Reading this in the archive, I am not sure what to make of Clifford’s thoughts on painful periods (of which I suffered for most of my reproductive life). Labeling dysmenorrhea as “an emotional disorder” appears to delegitimize patients’ pain and reinforces depictions of women as histrionic. Intimating that dysmenorrhea is inherited, not genetically, but through familial forewarnings of pain, is further delegitimizing. But in the same breath, he admits to treating the disorder on a strictly physiological basis. Dr. Clifford implicitly acknowledges the importance of validating his patients’ pain by rendering pharmaceutical treatment, but also believes that pain is emotional in nature. Does Clifford separate theory from practice, holding problematic beliefs about gendered pain but restraining those beliefs in his medical practice? How do researchers appropriately capture such contradictions in the same document, even the same paragraph, while attempting to tell a straightforward story?

To read Clifford's paper, "Anxiety: A View Point of the OB/GYN", please click here for a full PDF version.

To better understand this document, I would certainly need to conduct more research. Clifford’s collection contains numerous speeches and talks that would help me contextualize this source and determine its potential intentions; I would need to study them closely to trace topical and rhetorical patterns. I would also need to study dominant medical discourses on dysmenorrhea in the 1960s to understand if Clifford’s views fell within the normative realm of care. Moreover, since the document under study is (presumably) Clifford’s typed remarks, it is not certain that he actually delivered the talk and, if so, how it was received. I would need to cross-check the 1967 NMA conference program, search for any mention of the talk in the Journal of the National Medical Association, research official NMA archival material about that year’s conference, and perhaps check for references to Clifford in Black newspapers in case journalists reported on the conference. Importantly, I would need to read everything I can about Clifford himself.

Nevertheless, based on this one document and my limited knowledge of the author, I can surmise that Clifford, like most human beings, was a complex, paradoxical person who brought that complexity to his medical practice. He could believe one thing (dysmenorrhea is an emotional disorder) and act incongruently to that belief (treat dysmenorrhea as a biomedical disorder). I am reminded of historian Elsa Barkley Brown, who cautioned students and teachers of history that “people and actions move in multiple directions at once.”3 And I, the researcher, am also complicated, bringing my own experiences with the subject matter to bear on my reading of the document, lugging my desires for a clean, uncomplicated story about a Black OB-GYN to the archives, and wrestling with my disappointments when that story doesn’t pan out the way I envisioned. Researchers experience varying affects in the archive, entering with longings for particular kinds of historical “proof” and leaving with discontents about their discoveries.4 As I experienced at the Legacy Center, treating complicated historical actors and their archives with ambivalence and acclimating to evidentiary contradictions may prove a useful research approach.

The Maurice Clifford, M.D., Papers have recently been processed. You can view the finding aid for the collection here: ACC 278, Maurice Clifford, M.D., Papers.

1Coccia et al., “Ambivalence as a Feminist Project,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 49, no. 4 (2024): 779-805.

2Maurice Clifford, MD. Papers, Box 11, Folder 33: “Anxiety: A View of OB-GYN, 1967”. Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

3Elsa Barkley Brown, “African-American Women’s Quilting,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14, no. 4 (1989): 921-929.

4On archival disappointment and desire, see Britt Rusert, “Disappointment in the Archives of Black Freedom,” Social Text 33, no. 4 (2015):19-33; Stacy Wolf, “Desire in Evidence,” Text and Performance Quarterly 17, no. 4 (2009): 343-351.