Deep bonds and intimate friendships: Letters to Ada Pierce McCormick

by Jessica Pifer, Archives Intern

The majority of what makes up Ada Peirce McCormick’s materials at the Legacy Center is her personal correspondence; namely, the letters she received from her friends Dr. Emma Elizabeth Musson and Dr. Elizabeth Clark over the course of 40 years, beginning in 1908. As I have worked through Ada’s file, I am reminded of the deep bonds and intimate friendships that can be maintained even through a much less instantaneous form of communication than what I have grown up using, and I begin to form my own relationship with the women. Although the file consists only of the letters Ada received and none of the letters she wrote, therefore representing half of the conversation at hand, the close bond between these women is palpable.

We are not sure of the nature of the relationship between these three women, or how they came to be part of one another's lives, as Ada was not a physician, yet she was deeply connected to the medical community. The development and intimacy of their friendship rather than Ada’s connection to medicine—or lack thereof—is what makes this collection truly invaluable. Ada’s letters are a reflection of women’s history, as they provide insight into the relationships between women, as well as the unique experience of women entering a historically male-sphere; medicine.

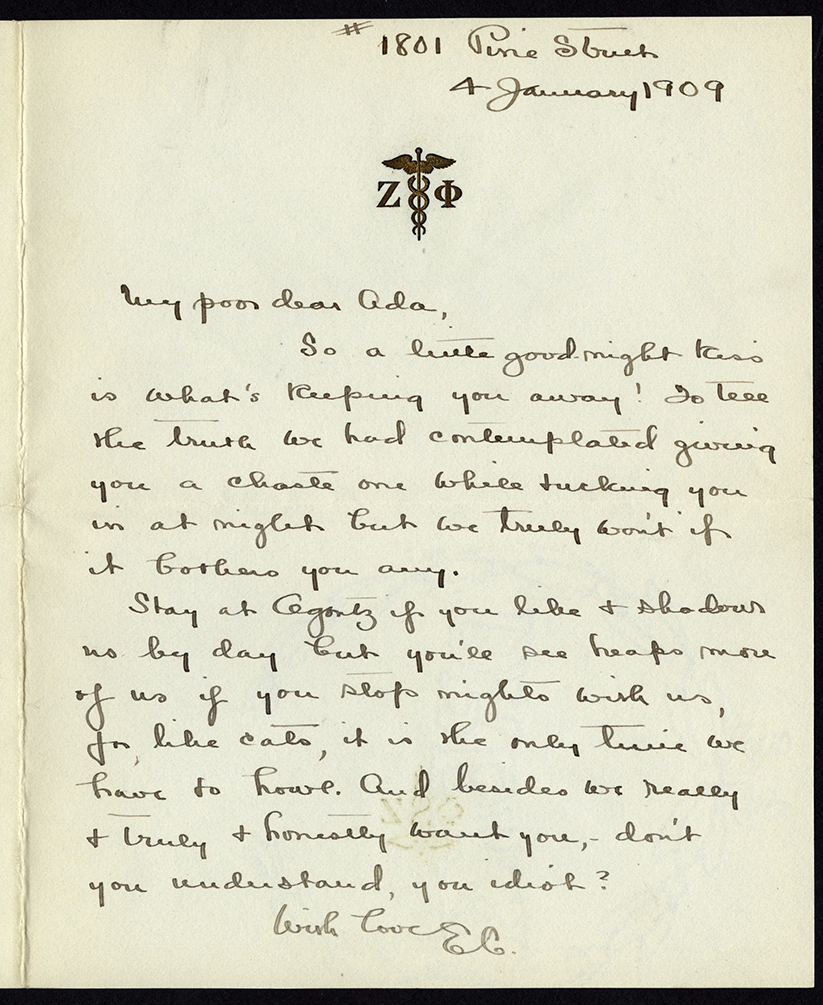

Elizabeth Clark, who in later letters signs off as Izzie, seems to share an especially close bond with Ada. In an earlier letter, dated in January of 1909, Izzie tries to convince Ada to come visit her and Emma Elizabeth Musson, or Elizabeth, in Philadelphia where Izzie studied and Elizabeth worked as a professor at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP). Although we do not have Ada’s letters, it seems as though Ada is concerned that her visit would be an imposition, as Izzie writes to Ada: “and besides we really and truly and honestly want you-- don’t you understand, you idiot” (a164_b01f02_002). It is clear that Ada does not want to burden Elizabeth or Izzie with her stay, but equally clear in the lighthearted and teasing way that Izzie speaks with Ada that the two women are close.

While it is unclear to me the exact nature of Ada’s visit to Philadelphia, it seems as though it is a personal visit rather than professional, as Ada was not a physician. In October of 1908, Izzie did offer professional advice to Ada: “stick to a certain kind of work—anything will do—until you perfect yourself in it—do everything for your own benefit for 5 or 6 years until your work has a certain value, then let yourself loose on the unsuspecting public.” [a164_b01f01_002] Izzie’s advice for Ada is not only insightful and supportive but it is truly timeless. In letters such as this one, I forget for a moment that I am an outsider looking into someone else’s past.

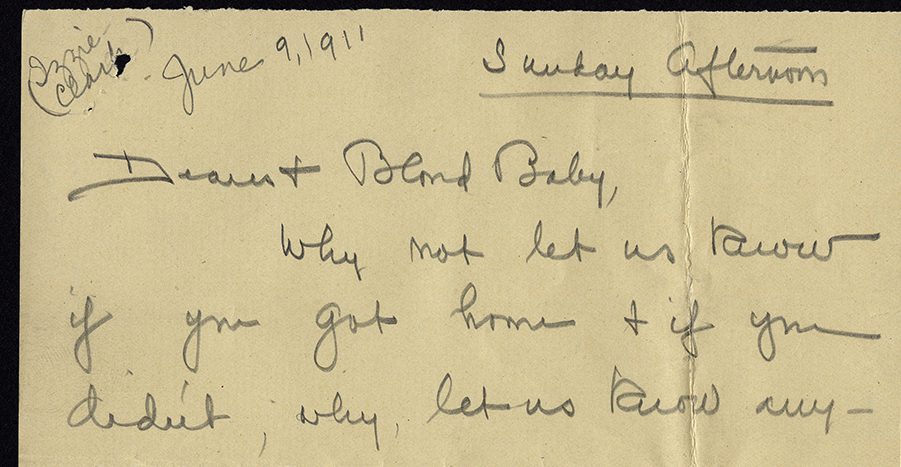

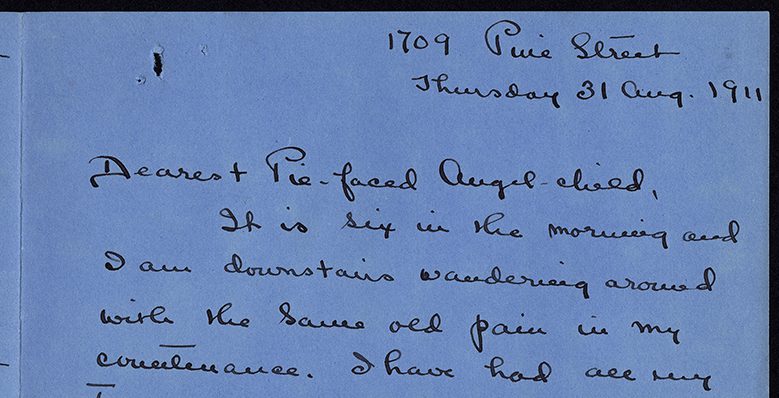

Izzie is a big personality, to say the least. She writes to Ada with beautiful imagery and exceptional wit; she is a kind and loving friend who is not afraid to be frank or honest. Over the course of their friendship, her deep love for Ada is clear even in the way she addresses her letters to Ada, as Izzie begins many of her notes with pet names for Ada such as “Kid,” “Kidlets,” “My Angelic Pup,” “Dearest Blonde Baby,” or “Pie-faced Angel-child,” among many other endearing nicknames.

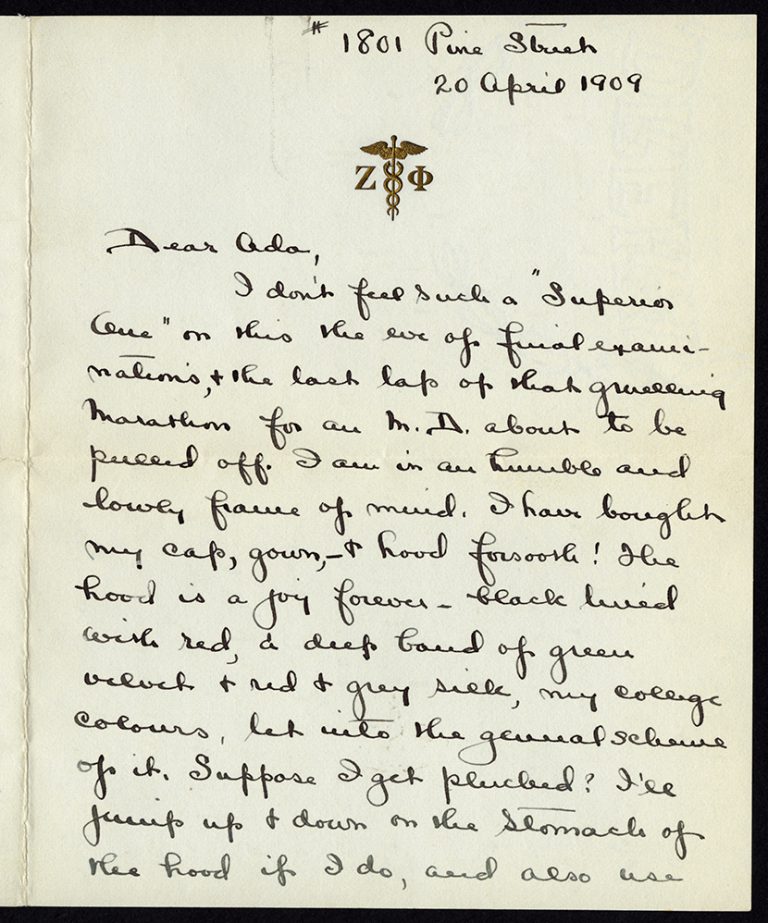

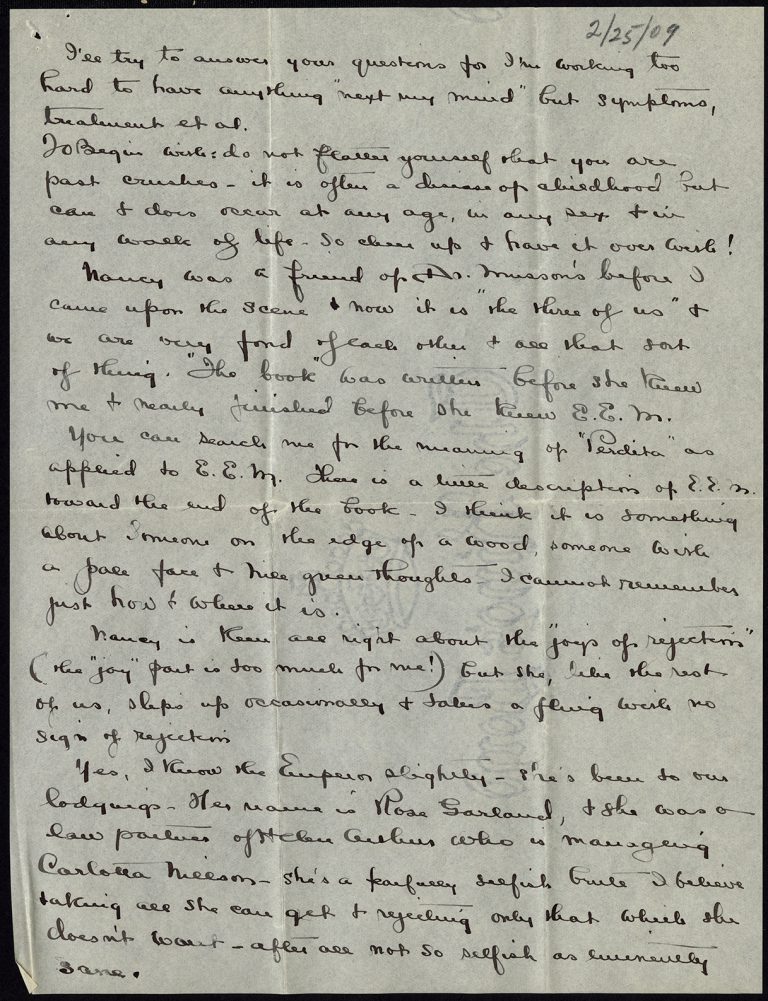

The women write to one another about everything: what goes on in their daily lives, the issues they’re facing at the time, and even about how silly they feel for being grown women with crushes. In one letter, Izzie writes to Ada about the stress she feels regarding graduation and sitting for the state board exam. In another, Izzie tells Ada “do not flatter yourself that you are past crushes—it is often a disease of childhood but can and does occur at any age in any sex and in any walk of life.” I see myself and my friends in these letters. I feel their academic stress, I am learning from their advice for one another, and their jokes make me smile. Through Ada’s letters I am able to not only imagine their lives, but I feel as though I am able to personally know these women.

Elizabeth F. Clark to Ada Peirce McCormick, 20 April 1909

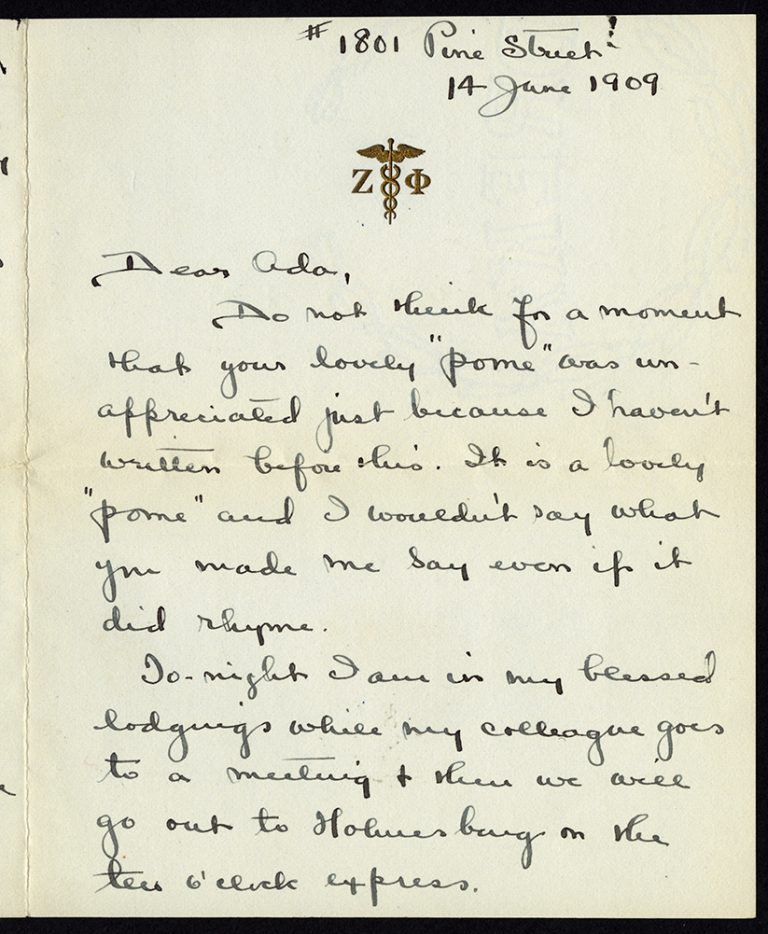

Elizabeth F. Clark to Ada Peirce McCormick, 14 June 1909.

Elizabeth F. Clark to Ada Peirce McCormick, 2 February 1909.

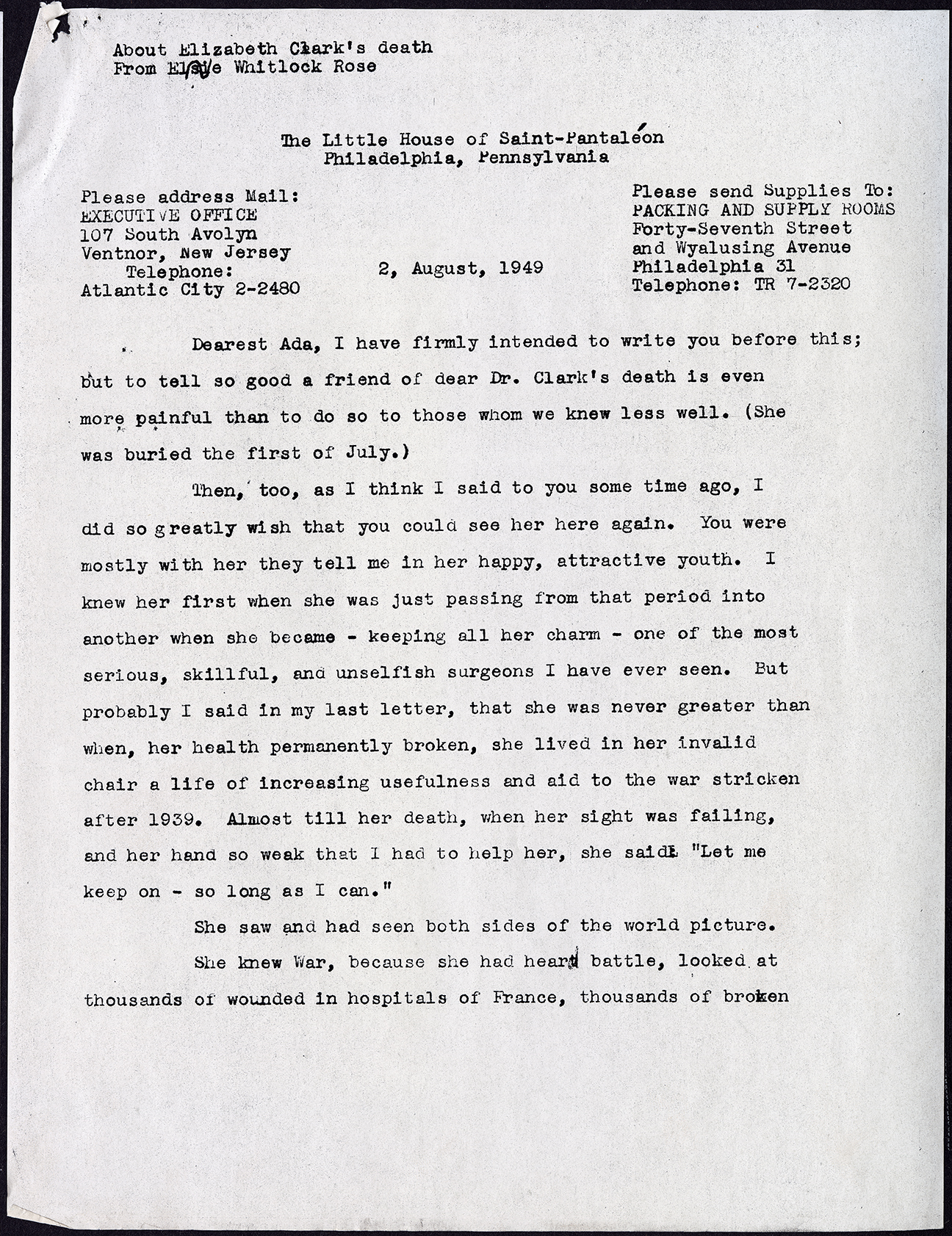

After scanning and processing more than 50 letters, I found a letter that Ada received on August 2nd, 1949 from Dr. Elise Whitlock Rose, a mutual friend between her and Izzie, informing Ada of Izzie’s death earlier in the summer of 1949. Dr. Whitlock Rose described Izzie as “one of the most serious, skillful, and unselfish surgeons I have ever seen,” reiterating my personal understanding of Izzie as a successful and strong woman. It was not until I was taken aback and genuinely saddened by the report of Izzie’s death that I realized how much of a relationship and a feeling of closeness I had developed for these women. As I have worked through Ada’s files and read her 100-year-old letters, I obviously understood that these women had passed away many years ago, but what I did not know was how alive Izzie and Ada would still feel to me.

Elise Whitlock Rose to Ada McCormick, 2 August 1949.

An individual’s body of correspondence has the unique ability to connect historians and researchers to the past in a very intimate way. By reading Ada’s letters, I have become connected to a period in history that has often felt foreign to me due to the significant differences between my life and the lives of women at that time. My hope is that through my work this summer digitizing Ada’s correspondence, other researchers will be able to develop their own relationship with her and her friends.