Picture Perfect: Teaching Analysis Skills with Fundraising Photography

by Elliott Earle, Educator Content Developer for Doctor or Doctress

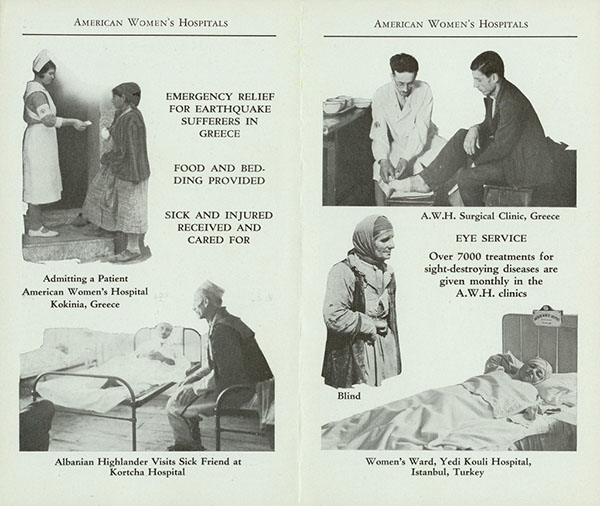

A patient in the American Women's Hospitals' Women's Ward in Istanbul,

Turkey.

Primary source analysis is a mine of educational value for social studies

teachers. Working directly with materials from the past allows students to

confront the complexities of history head-on and take ownership of their

learning. But in this teaching treasure trove, one of the most valuable gems

is often overlooked: photography. In many classrooms, primary source analysis

tends to revolve around text-heavy documents. But with the right tools,

pictures can engage many of the students that text sources could potentially

push away, while working the same critical thinking muscles.

It’s tempting to let those muscles take a break when looking at an old

photograph. The information found in frame seems more reliable and true than a

written account of that same scene.1 But just

like any other primary source, an image always has an "author" and is rarely

ever completely objective. "Sourcing heuristics"—that toolbox of questions

historians and students use to interrogate a source's context, author, and

purpose—are as important as ever when using historical photographs with

students.

Established during WWI to provide medical care to the devastated parts of

Europe, the American Women's Hospitals was one organization that left behind a

great deal of photographic documentation of both their foreign and domestic

work. Of the three collections on

Doctor or Doctress

that focus on the work of the AWH, two of them lean heavily on images to tell

the story. Like any other non-textual source brought into the classroom, these

stories will give some variety to any primary source analysis muscle workout

routine. But what the American Women's Hospitals in particular can offer is a

great opportunity to discuss the reliability of images and the importance of

the person behind the camera to what is captured in it.

The bandaged patient from above has been masked and cropped to fit on this

fundraising brochure page.

The pictures taken by the AWH depicting the

refugee crisis in Greece and Turkey following the fire of Smyrna

or the

conditions of the rural poor in Depression-era Appalachia

are important accounts of those situations, but like any written account,

they must be analyzed with a critical eye. Why was this image taken? What

were the photographer's goals? For the American Women's Hospitals, the

answer was frequently, if not almost always, fundraising. Photography was

critical to the AWH fundraising efforts stateside. Dr. Esther P. Lovejoy,

president of the AWH, complained in a letter to one of the organization’s

doctors that "THIS NATION HAS BECOME ILLITERATE IN THE ORDINARY SENSE. THEY

WILL NOT READ: THEY MUST SEE THINGS IN PICTURE FORM."2

Doctors in the field were often directed to capture scenes (either candid or

posed) on camera that would likely prove fruitful in their next brochure.

Dr. Lovejoy sent frequent letters scolding Dr. Etta Gray for not sending

back useful photos of AWH work where Dr. Gray was stationed in Serbia. "It

is just as hard for me to raise money on this side... without pictures of

the sick," Dr. Lovejoy wrote, "as it would be for you to run your hospital

without money."3

The AWH needed pictures and stories that would tug at the heartstrings of

America. In an exasperated complaint to Dr. Gray at the lack of useful

material being sent to headquarters, Dr. Lovejoy explicitly stated the kinds

of pictures they should be taking:

All I am able to get is some picture of a woman in uniform doing nothing in

which nobody is interested, and what I want is pictures of long lines of

wretched looking people and children standing in their dispensaries. We want

pictures of people sick in bed. We want pictures of people who have been

restored to health with a complete story under the picture regarding these

people... We want pictures of people who were blind, at the time when they

were blind and then pictures of those same people after their sight has been

restored by the work done by the medical women of the American Women's

Hospitals.4

These were the principles that guided members of the AWH in their efforts to

document the organization's work. And the influence of the creator's

motivations to what is shown in an image often extends beyond the actual act

of taking the picture. Many students today have a keen eye for spotting traces

of photo editing software in the pictures they see in their daily lives, but

it might surprise them to learn that this practice was also in use in the

early 20th century. Whether it was to accentuate certain aspects of the scene

or to help fit all of the pictures on a brochure page, the AWH photographs

were subjected to editing once they were developed. The evidence of this

editing is still visible: signage and AWH logos drawn over in pen for

emphasis, cut-outs, and crop marks can be seen throughout the original copies

in the records.

Is photo editing an inherently dishonest practice? How did the pressure from

headquarters impact the scenes that were captured in the field? What might

have been left out? Does the ultimate mission of the AWH impact how we judge

them for these practices? These are just a few of the complicated questions to

be wrestled with in light of this evidence. It forces the viewer to recognize

the layers of intent and bias between themselves and the scene captured in

that image, a vital skill to have for a classroom of budding historians.

1 Susan Sontag encapsulated the idea in her

essay "On Photography" when she wrote that unlike written documents, "[p]hotographed images do not

seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of

reality that anyone can make or acquire."

2 Dr. Esther P. Lovejoy to Dr. Etta Gray, 19

February 1921, Records of the American Women’s Hospitals, Box 15, Folder 129.

3 Lovejoy to Gray, 16 March 1921, Records of

the AWH, Box 15, Folder 129.

4 Lovejoy to Gray, 11 January 1921, Records of

the AWH, Box 15, Folder 129.