The Mystery of the Shrunken Head

By Chrissie Perella

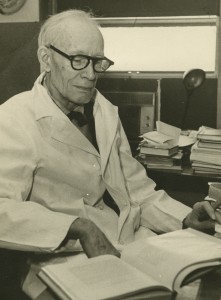

For the past several weeks, I've been processing the extensive Hartwig

Kuhlenbeck collection. Kuhlenbeck, born in Germany in 1897, was Professor of

Anatomy and, later, Emeritus Professor at Woman's Medical College, and

served as Major of the Medical Corps of the United States Army during World

War II. He traveled all over the world, including the Alps, Alaska, the

South Pacific, India, South America, and spent several years in Japan at the

Imperial University and Keio University in Tokyo as Dozent of Anatomy and

Comparative Neurology during the 1920s. He's an interesting man with an

interesting collection. While Kuhlenbeck deserves an entire blog post to

himself, one item in his collection is just begging to be written about.

Kuhlenbeck saved various memorabilia from his travels: souvenir postcards

and stationery, maps, museum booklets, hotel receipts. Fun stuff to look

through, and much the same as we save from our vacations today.

In 1951, Kuhlenbeck spent several months in South America, lecturing (in

Spanish, of course) at the Neurological Clinic of the University of

Montevideo, Uruguay; the Hortega Institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina; and the

Universities of Santiago and Concepcion in Chile. He visited "a number of

additional Medical Schools and Scientific Institutions...[to collect] material

for comparative neurological study." He also collected a shrunken head,

allegedly from the Jivaro people.

The Jivaro are South American Indian people living in Ecuador and Peru, north

of the Marañón River in the eastern part of the Andes mountains. They are

war-like and well-known for their talent of shrinking heads to the size of

apples.1 Kuhlenbeck described the

head-shrinking process as such:

In the manufacture of the skin tsantsas, the separated head is split by a

cut from the apex across the occiput to the rear end of the neck stump and

carefully peeled away from the skull; the skinned skull is thrown away.

The skin sack is then cooked for several hours in a boiler, where water

and plant juices, known to the Indians as conducive to shrinkage, are

mixed. Then the head-hunters sew the incision to guide the peeling skin

and again achieve a further shrinkage, and at the same time shape [the

head] by placing hot stones in the neck opening of the skin sack, and roll

the stones back and forth. Furthermore, the outer side of the head is

flattened with smooth stones and modeled. Finally, hot sand is poured

through the neck opening into the interior of the hollow head; so that the

final drying and shrinkage is caused, which can be completed by a kind of

incense on the fire.

During his visit to Ecuador, Kuhlenbeck wrote in his Tagebuch

about the day he purchased the shrunken head:

An old Indian woman, sitting there on a blanket spread out on the street,

offers a variety of handicrafts for sale at which I look. As I exchange a

few words with her, she pulls out of a basket a blackish, shrunken head,

the size of a small human fist, with a long dark mop of hair, which she

offers to sell to me for a few dollars...It is apparently one of those

designated as Tsantsa Trophies of the Jivaro (Jibaros), the wild

Indian tribes of the tropical jungle in the upper Amazon.

Clearly not as skeptical as some would be when offered such merchandise for a

measly few dollars, Kuhlenbeck seemed to believe it was the real deal:

The head, which the squaw offers to me, is obviously true – it shows the

face of a young person of about 20 to 30 years, with slightly Negroid and

some feminine traits. I am therefore not quite sure if it was a young man

or is a woman. In the latter case, the value would only have been a very

little as a trophy for the Jivaro. Also, it is probably a half-breed head,

perhaps the one Zambos. The lips are sewn, as is generally the case with

these heads, with only a single thread loop. Nevertheless, this shrunken

head offered to me is an unusual showpiece with an almost living facial

expression. Therefore, I pay the high price and put the head, like an

apple, in my coat pocket.

Now, meet Jürgen Jivaro (we here at the Legacy Center have dubbed it as

such, feeling it needed a name). The question is, "Is it authentic?"

Authentic in this case - a true tsantsa - means a shrunken human

head prepared with correct ceremonial and religious rituals by the Jivaro

people. I'm still undecided, but signs are pointing to it being a forgery -

whether human, it's very difficult to tell.

My first foray into Jürgen's authenticity was to find out what Kuhlenbeck

himself had written; luckily for me, he mentioned the date of his South

American tour in a short autobiography. From there it took several hours of

paging through his Tagebuch (day book, literally) until finding

some mention of the Jivaro - a tough task considering my German is a bit

rusty! With the help of Google Translate (quite possibly, the bane of

foreign language teachers everywhere), I soon discovered the means by which

Kuhlenbeck acquired Jürgen (as excerpted above).

Well, Kuhlenbeck seemed to harbor little doubts as to the authenticity of the

shrunken head, but that didn't settle it for me. So I did some digging. One

helpful article, "Shrunken head (tsantsa): A complete forensic analysis

procedure," listed diagnosis criteria for authenticating shrunken heads.

Jürgen fit only four of these criteria well.2

Another article, a case study written in 1975 about two shrunken heads in the

nearby Mütter Museum3, seemed to present evidence that Jürgen is not authentic.

So what did I find out about authentic tsantsa and forgeries? A

‘forgery’ or ‘fake’ can be either a shrunken human head not prepared with the

correct ritual (sometimes referred to as “tourist heads”2) or one made of an animal head (commonly sloth); animal hide; or even

plastic.3Here's what I found about our shrunken head, and why I

believe it's not authentic, but (best case) a "tourist head" or (worst case) a

fake composed of animal skin.

While Jürgen's skin is smooth and polished with what could be charcoal, and

there are stitches up the back of its head, it is clearly missing some

qualities authentic shrunken heads share. Yes, it's not uncommon for the hair

to be cut or for the string attached to the top of the head to be absent.

However, while Jürgen's ears seem to be blocked with some sort of material,

they're not pierced. Its eyes are not completely shut, let alone sealed. This,

and the fact that its lips are sewn through with only one thread as opposed to

three, seem to point to the head being a forgery. The Jivaro made certain the

lips and eyes were sealed and sewn tight to ensure the spirit could neither

see nor escape. Additionally, the thumb-sized depressions found on the temples

of authentic tsantsas are not noticeable.23

Blocked, unpierced ear

Side view showing eyes and lack of depression

Back of head showing stitching

Kuhlenbeck also mentioned that the shrunken head he purchased had "an almost

living facial expression." It has been stated that the Jivaros would

purposefully distort the heads to ridicule their enemies and made no attempts

to make the facial expressions look 'alive.'3

All this evidence leads me to believe Jürgen is a forgery, much as I would

like it to be authentic. Without the use of high-powered microscopes or DNA

testing, we probably won't know whether it is a human head. So what do you

think? Is Jürgen authentic or just a clever forgery?

1"Jívaro."

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia

Britannica Inc., 2014.

2Charlier, P.; Charlier, I-Huynh; Brun, L.;

Herve, C.; and de la Grandmaison, Lorin.

"Shrunken head (tsantsa): A complete forensic analysis procedure.”

Forensic Science International, 222 (2012): 399e1-399e5.

3Mutter, George L.

"Jivaro Tsantsas, Authentic and Forged: A Study of Two Shrunken Heads in

the Mütter Museum."

Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia

43, no. 2 (1975): 78-82.