“Go tomorrow to the hospital to see the She Doctors!”

By Melissa Mandell

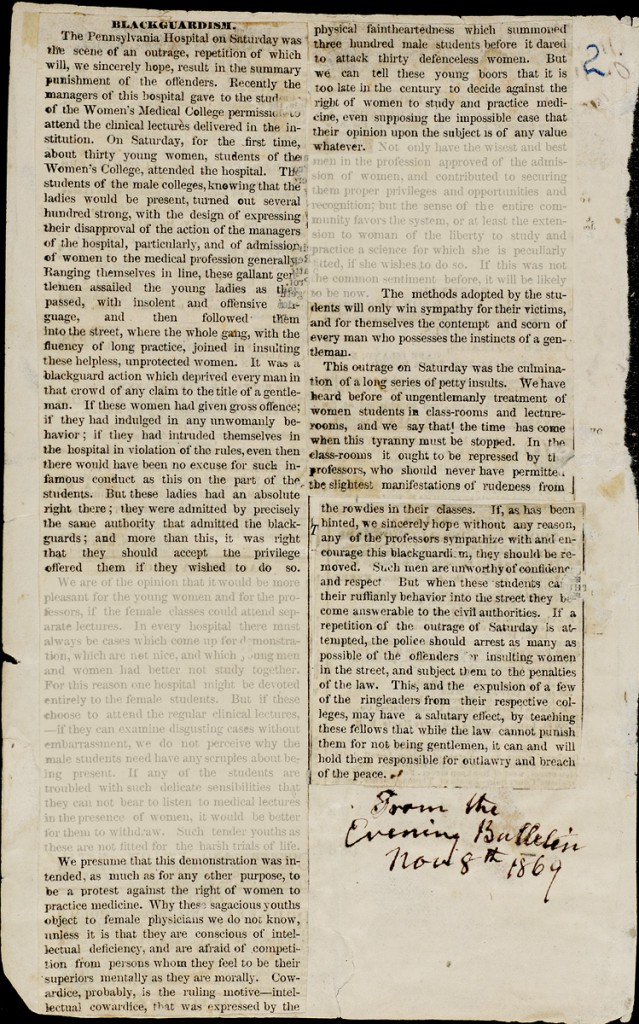

"BLACKGUARDISM. The Pennsylvania Hospital on Saturday was the scene of an outrage..." from the Evening Bulletin, November 8, 1869.; Document was abridged for the students.

Last week, Legacy Center staff presented a program to fifty seventh-grade students at the all-girls middle school of Springside Chestnut Hill Academy. The students were in the midst of “middle-session” – a week of interdisciplinary project-based study. Their project for the week was to create a newspaper based on “The Philadelphia You Never Knew.” Using documents from our Women in Medicine collection, we explored a little-known Philadelphia story from 1869: The Jeering Episode. The Jeering Episode, as it’s become known, refers to a day in 1869 when a group of students from Woman’s Medical College were harassed and verbally abused (epithets, spitballs, cat-calls) by male medical students when they attended a clinical lecture at Pennsylvania Hospital. The incident resonated with Woman’s Med students for generations as a symbol of their struggles to gain acceptance in the medical profession, and was key to the formation of the collective identity and institutional memory of Woman’s Med faculty and students.

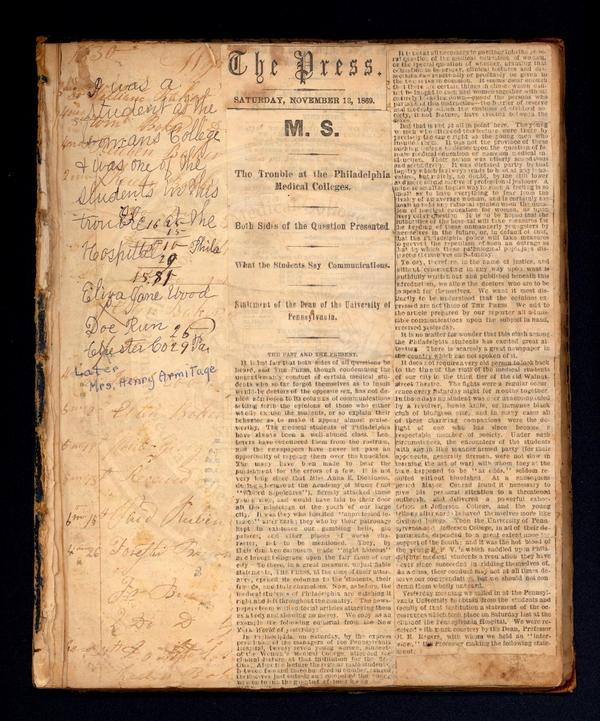

Since this history is primarily documented though newspaper clippings collected in a scrapbook kept by WMCP student Eliza Wood-Armitage (class of 1870), the Jeering Episode also provided an ideal opportunity to demonstrate how to use newspapers to piece together what happened and to investigate how people felt about the incident at the time, as reflected by the press reports and editorials.

One of the pages from Eliza Wood-Armitage's scrapbook that documents the Jeering Episode in 1869. The upper left column, inscribed by her, reads, in part: "I was a student at the Woman's College & was one of the students in this trouble at the hospital."

We also wanted to provide some perspective and show how the Jeering Episode, occurring almost 20 years after the 1850 founding of Woman’s Med, was a turning point for the school that became a shared memory for all of the students that came after. Among the 1869 news clippings we included a diary entry from Sarah Hibbard (WMCP 1870), a Woman’s Med student present at the incident reflecting upon the incident a few years later, and a 1926 clipping of an interview with Anna Broomall (WMCP 1871), another student who was present at what she calls “the mob of ’69.” Both pieces reveal how the passage of time affects the womens’ perceptions of the event, and illustrate the difference between reporting versus remembering.

Hibbard, from her diary, early 1870s: “…the conduct of the male students…needs no comments further than to say, that their “loss was our gain,’ for certainly they did lose and & certainly we did gain… if these poor fellows had sought to do us a life long favor they could not have done it more effectively than they did in their conduct towards us during those sessions.

Broomall, from a 1926 interview: “A friend of mine...handed me a slip of paper that had been passed among students of the University...I have the paper still. It read, " go tomorrow to the hospital to see the She Doctors!"...Next day, when we turned up at the clinic...pandemonium broke loose...The present generation should be given to know what such women have done for all other women.”

Before we arrived, the students had spent the morning learning about the parts of a newspaper--masthead, headlines, columns, by-lines-- and the difference between reportage and editorials.

But we still didn’t know how much they knew--about the history of discrimination against women (although this being an all-girls school, we suspected that there was some awareness of the issues around single-sex education), about the way news is created and distributed, about how history is documented and preserved. Does a 12-year old in 2012 know what a physical, pages-pasted-in scrapbook is? Had any of them ever read a hardcopy newspaper before today? To 12- and 13-year-olds, a newspaper is as remote an artifact as a typewriter, a rotary telephone, or a spinning jenny for that matter. For kids this young, the range of what constitutes “history” is of course much longer, but is it also somewhat collapsed? Is old just old, whether it’s from 1870 or 1970?

Our goals for the session were to impart the content (the story), to give a crash-course on how to use historical newspapers, and to stimulate some bigger-picture thinking about how memory and history are made. How do we balance reading comprehension, document analysis, historical thinking skills, and provide enough context to make it all effective and engaging for 50 students in 60 minutes?

We selected six documents from the collection, and gave each group of students two of those documents to read. We asked them a lot of questions so that they would be the ones interrogating the material and telling each other parts of the story. And we were prepared to follow the discussion wherever it took it us. Below are some highlights of the ensuing discussion.

In 1 WORD, describe how this story made you feel when you read it.

- sexist

- unsurprised

- disgusted

- appalled

- empowering

- unfair

- disrespectful

These students did not seem to be flummoxed by the language of 19th-century newspapers -- the archaic words, the decidedly non-objective language, the use of 40 words when 10 would suffice…So once we knew they “got” it, and reacted accordingly, we asked them to dig a little deeper -- the document analysis portion of the program:

Who wrote this document? (Man or woman? Where they present at the incident? Other thoughts?)

What did they think about the incident? (What was the point of view?)

Circle specific words or phrases within the document that support your answer.

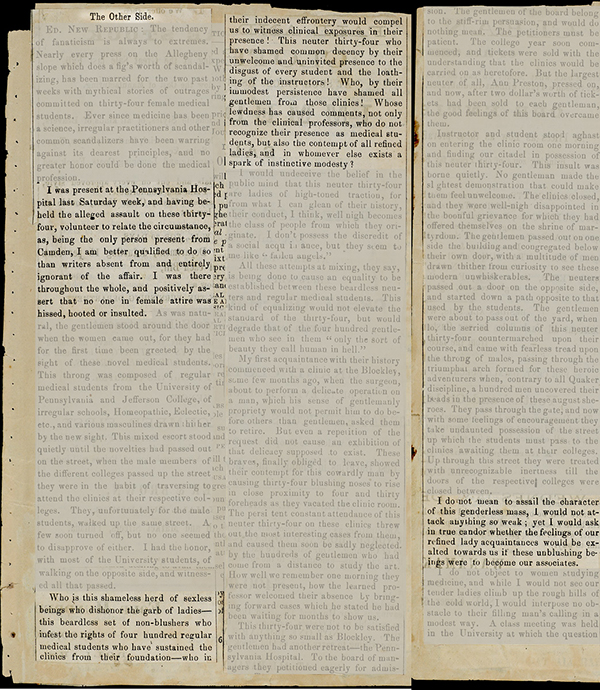

Considering that none of the newspaper clippings had by-lines, the students had to make their educated guesses based solely on the text. Most correctly deduced that the majority of the clippings were authored by men who had not been present at the event, but who were sympathetic to the female students and simultaneously outraged at the male students’ behavior. There were some questions about whether there were female journalists at the time, since some of the articles were so intensely pro-woman. One group with the Anna Broomall clipping figured out that whether it was written by a man or a woman, it was clearly an interview with Broomall and consisted mainly of her thoughts and recollections. One notable exception to all of the pro-woman sentiment was the article entitled, “The Other Side,” written by a male student who claimed to be present that day, and who vehemently denied that any harassment of the women took place. “ I… positively assert that no one in female attire was hissed, hooted, or insulted.” He also vehemently denied that the women were in fact, real women -- one student seized on this, er, colorful quote:

“Who is this shameless heard of sexless beings who dishonor the garb of ladies—this beardless set of non-blushers who infest the rights of four-hundred regular medical students…?”

"The Other Side." Re-published in several newspapers in November 1869. Document was abridged for the students.

Our go-to question for student groups: What do you wish you knew that isn’t in these documents?

- Were there women journalists at this time? [c.1869]

- What happened after [the Jeering Epsiode]?

- How they came to an agreement since woman can become doctors now

- Did the women learn anything at the lecture that day?

- What were the men thinking when they acted that way [harassed the women] and what did they think afterward?

- Why did woman’s Med eventually let men in ? [WMC went co-ed in 1970, a hundred years after the Jeering Episode]

- How did they get permission to start an all-female medical school? [WMC was founded in 1850]

- Did the men get in trouble?

- If there were no women doctors, were there women professors to teach the female students when WMC first opened?

- What gave the men the right to think that they were better than women?

This points to perhaps the most important lesson for the budding historian: research in the archives usually raises more questions than it answers. And the Springside students certainly asked some excellent ones. Most of them are answerable by digging further into our collection; others, not so much. Especially that last one.

You can see the all six documents used in the session, in their unedited versions, here