Criminology and Justice Studies Professor Explores Effects of Recreational Marijuana Legalization in NJ with Reducing Inequality Research Grant

By Liz Waldie

February 10, 2023

One of the most significant developmental periods of our lives happens between the ages of 18 and 25. It’s meant to be a time of learning and growth; going to school, participating in extracurricular activities, exploring the world of higher education and transitioning into the workforce. But getting caught in the legal system can throw a wrench into those plans.

Research shows that being arrested once can lead to more arrests, more convictions and more incarcerations. It creates a “trip wire for additional system contact,” according to Assistant Research Professor of Criminology and Justice Studies,

Kathleen Powell, PhD.

This kind of cycle can hinder education, job security and general peace of mind. Constant police involvement has proven detrimental to individual and community health, and a common reason for increased law enforcement presence is marijuana usage, or simply the suspicion of marijuana usage (such as detection of an odor). It is also a prime reason why many young people are involved with the system in the first place.

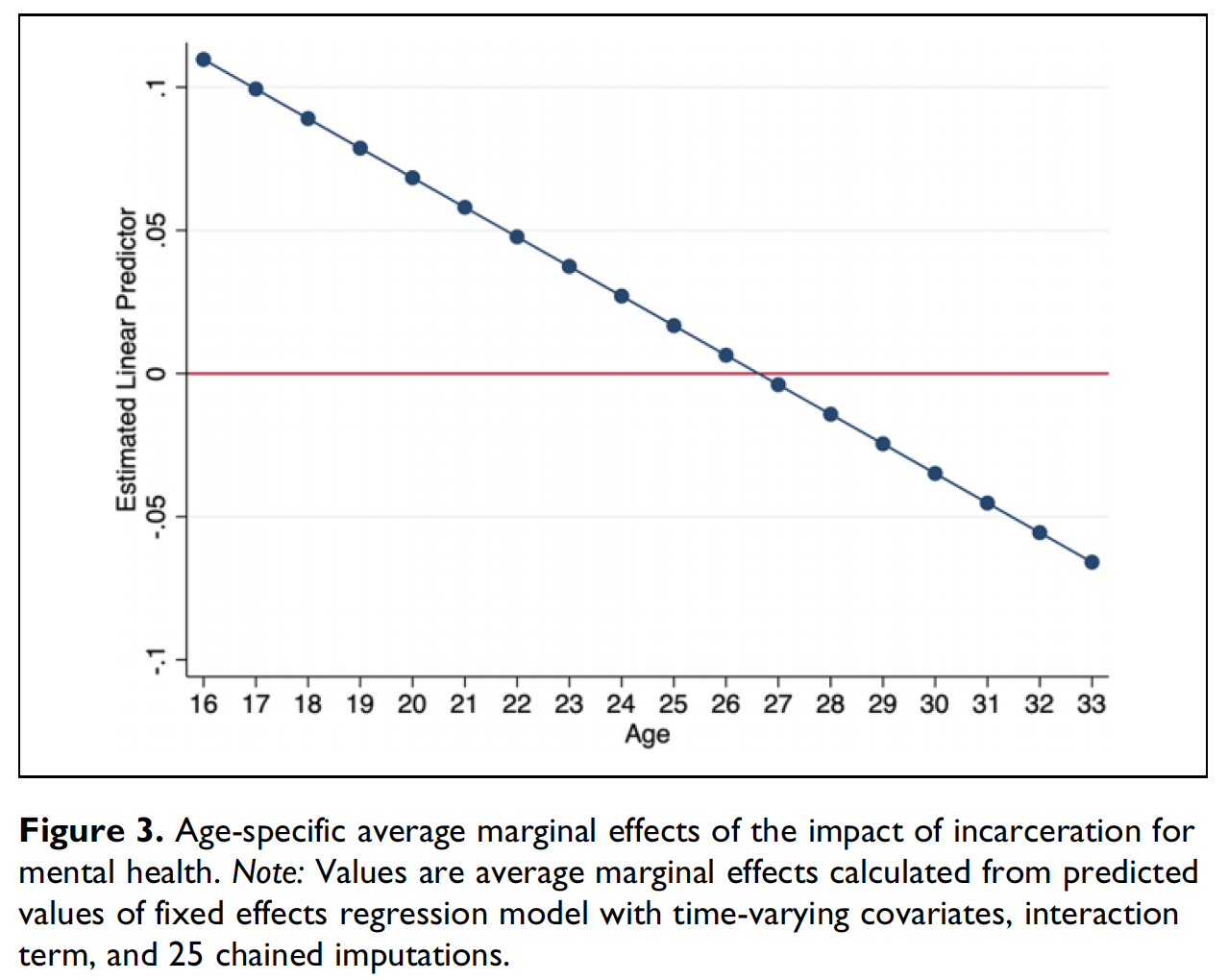

Powell has always been interested in understanding the repercussions of arrest, conviction and confinement of youth. As an intern at a law firm, she participated in advocacy work for reform in the juvenile justice system. Her dissertation focused on how the consequences of involvement in the legal system varies by age of involvement. According to her research, she found that being incarcerated is more harmful to mental health when it happens in early adulthood relative to later in life.

Powell has always been interested in understanding the repercussions of arrest, conviction and confinement of youth. As an intern at a law firm, she participated in advocacy work for reform in the juvenile justice system. Her dissertation focused on how the consequences of involvement in the legal system varies by age of involvement. According to her research, she found that being incarcerated is more harmful to mental health when it happens in early adulthood relative to later in life.

Now, after receiving a $544,000 Reducing Inequality Research Grant from the William T. Grant Foundation, Powell intends to further her research by exploring how the legalization of recreational marijuana in New Jersey affects Black, Hispanic and White young adults.

“The Foundation was very receptive of my proposal to do this work in a theoretically-informed, community-engaged and policy-relevant way, which is exactly how I, my team and my CJS department colleagues strive to do research. I’m thrilled to have support to do this project in this way,” Powell smiled.

Patterns show that the rate of marijuana use is similar across young people of different races and ethnicities, but historically, there has been disparate law enforcement of those behaviors.

“What I’m trying to investigate in this project is whether legalization eliminates some of these inequities in enforcement,” Powell explained. “If it does, what does that look like, and how can that inform other jurisdictions that are also looking to legalize marijuana?”

When the legislation to legalize the recreational use of marijuana was passed, New Jersey automatically expunged, or erased, the records of those who had previously been arrested, charged or convicted of marijuana offenses. Typically, expungement is not automatic and involves a costly, time-consuming process—one that is not very accessible to underserved communities. Automatic expungement could provide massive relief to those with previous records.

But did individuals eligible for expungement actually get their clean slate? Was it communicated to them that their records were wiped? If so, what did they do with that knowledge? Were they more likely to look for a job, apply for student loans or buy a home? That’s exactly what Powell’s team intends to find out: how this law got passed, how it’s being implemented all the way down to the municipal police department and court administration level, and whether the barriers that stand in the way of those affected by these records have been lifted.

Jordan Hyatt, PhD, director of the Center for Public Policy; Loni Tabb, PhD, professor of biostatistics in the Dornsife School of Public Health; Nathan Link, PhD, assistant professor of criminal justice at Rutgers University–Camden; consultant Sarah Lageson, PhD, of Rutgers University–Newark; and consultant Christopher Uggen, PhD, of the University of Minnesota will join Powell for this three-year study. The team will conduct a statewide survey and interviews with young adults who were arrested for marijuana offenses prior to legalization, in partnership with a youth advocate programs in Camden County, their main field site. Using a collaborative approach, the youth advocates will ensure that the team asks the right questions of their young audience and assist with recruiting eligible participants through community organizations.

“Working with the community and incorporating their voice into our research design is important, because they have experienced the historical legacy of this enforcement firsthand,” Powell said. “Their perspectives will really enrich our study, and we hope our findings will assist their advocacy work within their communities.”

Powell noted that New Jersey is an opportune place to conduct studies. In her words, criminal justice reform is often “bottom up,” meaning reform happens at a municipal or city level. New Jersey is unique in that their legislation involves state-level reform from the “top down,” a process that creates a more uniform implementation context and allows for comparisons of outcomes across communities.

Being stopped by a police officer while going about daily routines—such as on the way to school—is not normal, yet this is something that regularly happens in some communities, like Camden. This legislation presents an opportunity for detrimental experiences like that to become less common. Camden, while more impoverished with a more concentrated law enforcement presence, is a lot like Philadelphia and has historically faced high rates of violence and drug law enforcement. Powell believes that these challenges have the potential to diminish down the road, due in part to the decriminalization of marijuana that may reduce arrests and stabilize communities.

“I absolutely think this work can have spillover benefits for reducing violence. With less enforcement, residents might be better able to heal, support one another and mobilize to address shared challenges, perhaps resulting in less violence,” Powell said.

By speaking with people directly witnessing whether the police are doing their jobs differently, Powell hopes to gain insight into whether the benefits of these changes are being realized, and if they truly can reduce racial inequalities in the legal system.

“I’m excited about this project, because it will not only study the consequences of system contact for young people during this important developmental period, but will also provide insight into if and how changes to drug law policy are one type of legal system reform through which the system can become more equitable,” Powell said. “We’re addressing issues that have contributed to the size and punitiveness of the American criminal legal system as it functions today, while including the voices of those affected by it.”