Biological Sciences Major Lakshmi Parvathinathan Dreams of a More Inclusive Future

By Gina Myers

February 15, 2022

Applying to college can be a challenging process for high school students and their families. And it can be especially challenging if your legal status limits whether you can receive federal aid or if you qualify for in-state tuition—and it could even threaten your ability to complete a four- or five-year degree program.

This was the experience of biological sciences major Lakshmi Parvathinathan.

Parvathinathan stands with other student advocates from Improve the Dream in front of the US Capitol.

Parvathinathan stands with other student advocates from Improve the Dream in front of the US Capitol.

“Initially none of my high school counselors knew how to help me because they had never met someone who was in this weird limbo,” explains Parvathinathan. “Initially someone thought I was undocumented and gave me a brochure about DACA, but that didn’t fit me. You’re not a real international student because you’re not coming here for the first time, but you’re also not considered under DACA because of the status you do have.”

While in recent years more attention has been brought to undocumented students, also known as Dreamers, through Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), Parvathinathan is in a different class of students—those who have grown up in the United States as child dependents of long-term visa holders but who will age out of their dependent status and face deportation on their 21st birthdays. They call themselves Documented Dreamers.

An American Dream

Like many immigrants to the United States, Parvathinathan has a story that is complicated and relies so much on things outside of her control.

Born in India, she moved to the United States when she was three years old under her father’s L-1B work visa. When her parents applied for an extension of the visa, it was denied, so Parvathinathan was pulled out of school in the third grade and her family returned to India. They were able to move back to the United States before Parvathinathan began 5th grade, but they could not be certain how long they would be able to stay—their fates left up to the H-1B lottery. Luckily, when Parvathinathan was a freshman in high school, her parents were selected in the lottery, and she has been on an H4 visa ever since.

“I thought, ‘We finally won! I don’t have to worry anymore.’ I thought getting that meant everything would go away,” she says.

However, her parents explained that Parvathinathan would eventually age out of her dependent status due to the greencard backlog affecting Indian immigrants and have to begin the whole process for herself. In the meantime, she also could not have a job because she did not have work authorization, and she would be considered an international student when she applied to colleges. In order to stay in the United States beyond her 21st birthday, she would have to apply for a student visa and indicate that she did not have plans to stay in the United States after graduation—even though the US has been her home for nearly all of her life.

Parvathinathan’s status has also determined where and what she studies. Student visas allow students to stay up to one year after graduation if they have a non-STEM major. However, if they major in STEM, they can stay for up to three years. This works well for Parvathinathan, who wants to be a doctor and is on the biological sciences pre-med track.

However, her international status will be a problem when applying to medical schools because most medical schools in the United States do not accept international students. Drexel is an exception, but only if the student attends Drexel as an undergraduate. Though this will hopefully work out for Parvathinathan, the situation is still frustrating.

“It feels like my entire experience of growing up here in the US is invalidated—the 14+ years I’ve lived here to only be considered an international student and have to start everything all over,” she explains. Her student visa was recently approved after nearly 15 months of applying.

Improving the Dream

Though she did not know others going through it, Parvathinathan’s situation was not unique—she was one of over 200,000 young immigrants navigating this tricky system. Upon discovering the organization Improve the Dream, a youth-led advocacy group for Documented Dreamers, she would soon connect with others and find a sense of community that she never had before. The organization would also introduce her to the world of advocacy.

“I never really felt like I had a voice in government because I can’t vote,” she says. “Also, I wondered, if I do speak up, what happens to my immigration status? I didn’t know that you could reach out to congressional offices, and they will listen.”

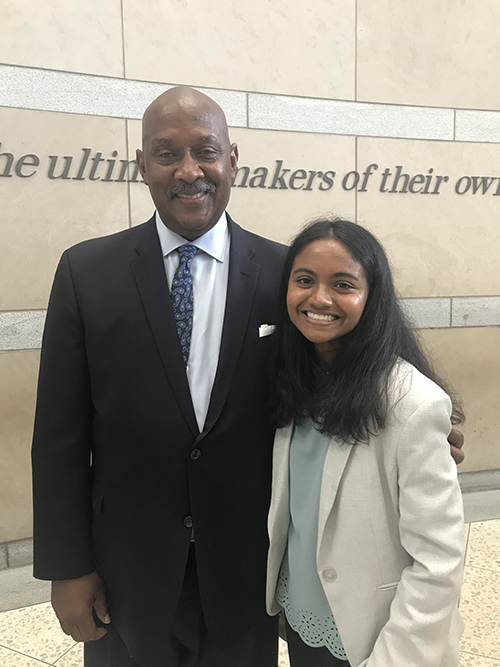

Parvathinathan stands with US Representative Dwight Evans, who cosponsored the American Dream and Promise Act of 2021.

Parvathinathan stands with US Representative Dwight Evans, who cosponsored the American Dream and Promise Act of 2021.

Documented Dreamers have historically been left out of solutions for kids who were brought to the United States at a young age because of their status. Improve the Dream is aiming to change that.

With guidance from Improve the Dream, Parvathinathan began setting up meetings with congressional representatives to share her experience. Serving as the organization’s Operations Manager, she leads community calls for Documented Dreamers, manages the Digital Strategy team, helps members feel welcome and heard, and guides them as they navigate the system and share their stories. In a year of advocacy and community-building, she has held numerous meetings, traveled to Washington DC twice to meet with congressional staff, senior officials from the Department of Homeland Security, the White House immigration team, and immigration organizations and national business organizations. She even got to share her immigration story with President Biden when he was in Philadelphia for a Voting Rights event this summer. Her advocacy efforts and story have also been featured on CNN and The Verge.

Parvathinathan feels that her work with Improve the Dream has not only given her a voice, it has also given her hope and a sense of belonging. She explains that up until last year, she could not bring herself to openly talk about her situation without breaking down as her status has always taken an emotional and mental toll on her.

In March the American Dream and Promise Act was introduced in the House, and for the first time it included Documented Dreamers. In July, the bipartisan bill America’s CHILDREN Act, which would provide a pathway to citizenship for Documented Dreamers, was introduced in the House, and in the fall the bill was introduced in the Senate.

Parvathinathan has learned how much education plays a role in advocacy. Many people she has spoken to, simply didn’t know about Documented Dreamers. She also points to the bipartisan support for the America’s Children Act as proof of what awareness can do.

With Drexel’s goal of being the most civically-engaged university, Parvathinathan’s dedication can serve as a guide for others. Rogelio Miñana, PhD, vice provost of global engagement, agrees. “Lakshmi represents the best a Drexel student can be: academically strong, but also connected to the very real challenges we face as a society. She uses her intellect, her perseverance, and her deep commitment to diversity to fight for what she believes,” he says. “She is the kind of purposeful student and citizen, engaged locally and internationally, we want to educate at Drexel.

“The United States was founded on the premise of both equality and diversity, although our laws often take a long time to catch up to our ideals. Documented Dreamers are in a legal limbo in this country today, and Lakshmi and hundreds of thousands of others in her situation are making sure Congress does not forget them.”

There is still much work to be done and the Improve The Dream community has been working on gaining the support of Senate offices for America’s CHILDREN Act which would permanently protect children from aging out of the system. Parvathinathan hopes that all bills going forward will include all children who grow up in this country as Americans and she hopes others will be inspired to take action to help raise awareness.