WELL Center Researcher Explores Food Addiction with NIH-Funded Grant

By Liz Waldie

December 20, 2022

Before being proven as addictive and damaging, cigarettes gained the attention of children through relatable slogans, cartoon characters and attractive designs. Only with marketing regulation and research detailing the destructive effects of tobacco did smoking slowly become less attractive to its young audience. But the marketing of harmful substances to vulnerable populations hasn’t gone away entirely. Instead, it has switched focus to another product: ultra-processed foods, commonly known as “junk food.”

“Nicotine products used to be advertised to kids with the cartoon Joe Camel, and now we see that same strategy used to market fast foods and packaged snacks,” said

Erica LaFata (formerly Erica Schulte), PhD, an assistant research professor in the

Center for Weight, Eating and Lifestyle Science (WELL Center). LaFata believes that ultra-processed foods are at the heart of many public health concerns, and it could be because these foods are addictive.

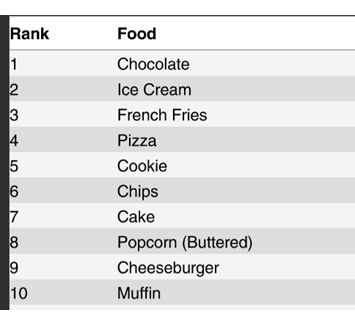

In a previous study published by LaFata, these 10 ultra-processed foods were reported by a sample of 504 individuals to be the most addictive.

In a previous study published by LaFata, these 10 ultra-processed foods were reported by a sample of 504 individuals to be the most addictive.

When nicotine was proven to be addictive in the 1980s, many tobacco industry leaders made the jump to the food industry, advertising processed foods with similar tactics to cigarettes. Interestingly, obesity and diet-related diseases like type 2 diabetes increased in the ’80s, as well. It’s no secret that society is focused on the physical effects of what we eat. But what we consume doesn’t just affect our physical health. LaFata says the psychological effects of food are underexplored, and the risks are high.

LaFata’s time working in a neuroimaging lab ignited her interest in food addiction. Two researchers had been conducting separate studies around impulsivity—one focused on smokers, the other on people with binge eating disorders—and both interpreted their results similarly. The idea of food addiction is controversial and has only emerged recently. Over the years, our food environment has significantly changed, most notably in the widespread availability of ultra-processed foods.

“People are typically exposed to their first ultra-processed food under the age of two, so people are growing up with them,” LaFata put the issue into perspective. “If we think of these foods as addictive, then there is now a whole subset of individuals who are susceptible to developing addictive disorders. And if that’s the case, we are starting exposure earlier than any other reinforcing substance that’s ever been known.”

Existing studies show that 10–15% of the population exhibit the presentation of food addiction, which is almost identical to rates of smoking and alcohol abuse disorder. While not every person is expected to experience an addiction to ultra-processed foods, it still poses a very real risk to public health. But ultra-processed foods are varied and complex. If they are addictive, it begs the question: what is the reinforcing ingredient? LaFata hopes to discover the answer through her new research study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

LaFata joined the WELL Center in August 2021, after earning her PhD from the University of Michigan. She saw the center as the perfect opportunity to kickstart her research career, as it is composed of obesity and eating disorder researchers all working toward a common goal. After two years of developing a proposal, LaFata was awarded a $755,000 K23 grant from the NIH for a five-year research study titled “Biobehavioral Reward Responses Associated with Consumption of Nutritionally Diverse Ultra-Processed Foods.”

For her study, LaFata will work with a sample of male and female adults, giving them different types of ultra-processed foods and examining how their metabolisms—things like blood sugar, glucose and hunger hormones—respond differently to these foods. LaFata is focusing on adults, because their neural responses are more solidified than children’s, whose brains are still developing.

Participants in the study will also rate indicators associated with the addictive potential of substances, such as craving and satisfaction, or the urge to consume more. These feelings are known to track with later reinforcement and continued substance use. It is LaFata’s hope that, by running foods through an addiction paradigm, the study will help us understand more about which ingredient is most important for the development of addiction.

LaFata noted that two suspected candidates for the reinforcing addictive agent are artificially elevated amounts of fat (such as hydrogenated oils) and refined carbohydrates (such as white flour and added sugars). The combination of fat and refined carbs does not exist in any naturally occurring foods other than breast milk, and breast milk is evolutionarily meant to be reinforcing.

“It’s a very interesting parallel between reinforcement and palatability, to drive additional consumption,” LaFata said. “My project is trying to understand the differences in addictive responses from a biological standpoint and a behavioral standpoint, regarding how different responses depend on whether ultra-processed foods have fat, carbohydrates or both.”

As it stands, there is a lot of personal responsibility when it comes to food. We’re told what we should eat, and then it’s up to us to regulate that, and to teach children what foods to avoid. It puts the blame on consumers, not the industry, when people develop food-related diseases. LaFata believes that until there’s systemic change, we’re not going to see a change in our food environment and mental wellbeing. What ultimately worked with tobacco was the truth campaign. By providing concrete evidence of the addictive nature of ultra-processed foods, maybe we’ll see similar public policy changes and marketing restrictions.

“We have this multibillion-dollar industry, and I think my work will be very controversial, but that’s something that excites me,” LaFata explained. “It makes me feel like there is a lot of potential for my work to create change.”

LaFata anticipates that recruitment for the study will start in 2023. For more information, you can email her at es3344@drexel.edu.