Geoscience Major Completes Award-Winning Project in Seafloor Volcanology

By Kylie Gray

Photos by Nick Barber

Drexel Geoscience student Nick Barber in Yellowstone National Park

Drexel Geoscience student Nick Barber in Yellowstone National Park

December 4, 2017

It was a summer that would make any adventure blogger envious: 12 days at sea aboard a 273-foot vessel, treks through the wilds of Yellowstone National Park, nights beneath the stars on Oregon’s massive stratovolcano Mount Hood. Geoscience major Nick Barber ’18 did all of this — along with award-winning conference presentations and innovative research — in the name of science.

As one of Drexel University’s first Ernest F. Hollings Scholars, Barber spent 10 weeks in Newport, Oregon, for a seafloor volcanism internship at the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. He followed the trip with a research excursion to Yellowstone with Drexel’s Loÿc Vanderkluysen, PhD, a volcanologist and assistant professor in the Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science.

Mapping the Seafloor

The Hollings Scholarship, administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, awards undergraduate grantees a paid internship and two years of academic assistance. The process of finding an internship, Barber says, is sort of like cold-calling scientists. With the possibility of working with any willing NOAA scientist in the country, Barber contacted the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, which studies geologic processes beneath the ocean.

Barber was invited to work on one of PMEL’s principal projects, the Earth-Ocean Interactions Program. The program examines hydrothermal venting — superheated jets of water and metals on the ocean floor formed by pockets of molten lava — at Axial Seamount, an active volcanic site located 300 miles off the Oregon coast.

The Pacific Ocean off the coast of Oregon.

The Pacific Ocean off the coast of Oregon.

“Over the past 30-plus years, PMEL has done a lot of the ‘firsts’ in seafloor volcanology,” Barber says. “It’s cool because, as I learned during this internship, the majority of volcanic processes are happening below the ocean — constantly and at much greater magnitudes than on land.”

Barber’s internship was programming-based, he says, even though he had limited programming experience. He spent the first few weeks working through the complexities of MATLAB software, which he would later use to conduct data analyses.

“I had some self-taught programming experience, but this summer really tested me,” Barber says. “When I hit walls or had a bug in my code, there was no one there who could help me.”

Barber was working with data called tilt, which is essentially a measure of how the ground is forming. The tilt meters did not output the data in a way that could be easily processed, but Barber devised a way to analyze it in MATLAB. He compiled his findings into time-lapse videos that illustrated the seafloor change at Axial Seamount leading up to and following its last known eruption in April of 2015.

The project earned Barber an exceptional presentation award at NOAA’s Science & Education Symposium in August — but, perhaps more exciting, the videos showed something unexpected that could lead to new knowledge in the field of seafloor volcanology.

“We’re still working out what to do with the videos because they show things that we didn’t know before and can’t really explain — things the seafloor was doing that no record had captured before,” says Barber. “The PMEL scientists need to square the videos with previous models, and they’re still figuring out how to do that.”

Science on the Open Seas

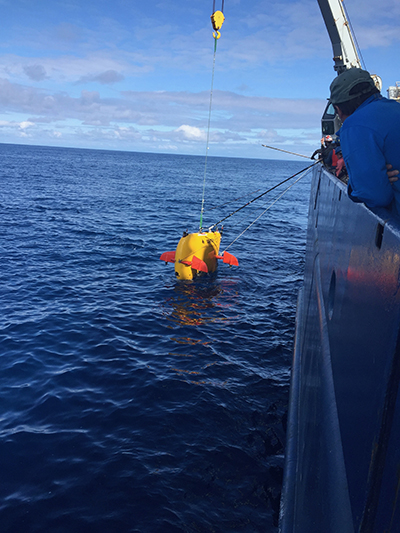

WHOI’s autonomous underwater vehicle “Sentry” was used in addition to the ROV “Jason.”

WHOI’s autonomous underwater vehicle “Sentry” was used in addition to the ROV “Jason.”

Barber’s internship with PMEL’s Earth-Ocean Interactions Program coincided with their annual trip to Axial Seamount. He spent 12 days aboard one of the biggest research vessels in the U.S. with the more than 50 crewmembers and 20 engineers who collaborated on the expedition. The team used “Jason,” the Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution’s remote-operated vehicle, to traverse the perimeter of the underwater volcano.

Barber logged the activity of the robot, supported the scientists, and even helped name a hydrothermal vent (“Limoncello” due its yellow color — and because some of the scientists were eager to get to a bar after the long trip!). As a rookie scientist, he had tough shifts — 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. — but he says he found the experience exceedingly valuable.

“I learned a lot from the engineers and crew, especially some of the younger scientists who are grad students or young faculty,” he says. “They gave me a lot of helpful advice, like how to work with data in less-than-ideal conditions and come up with creative solutions.”

The friendships he made on ship continue to be valuable as he applies to PhD programs in volcanology. It’s a field that comes with a certain “cool factor,” Barber says, but which the general population knows little about.

“The biggest misconception that people have is that volcanoes are not a present and real threat,” he says. “An eruption is something that could happen in our lifetime in the U.S. It’s not like we need to have bunkers built, but in terms of regularly occurring volcanic eruptions, we would be better prepared with more investment in monitoring. Only a handful of U.S. volcanoes have the gold standard, which is gas monitoring.”

Heating Up

Sapphire Pool, Yellowstone National Park

Sapphire Pool, Yellowstone National Park

Barber gained firsthand experience in gas monitoring later that summer at Yellowstone National Park. Alongside Vanderkluysen, two graduate students and a scientist from the Academy of Natural Sciences, Barber helped collect data at five geothermal features as part of a research co-op.

“Walking with hundreds of pounds of gear through the woods, there were days when I was really fatigued,” Barber recalls. “Even if you’re tired though, you can’t throw in the towel or get hurt. You have to stay a useful member of the team. I was lucky to have great mentors who prepared me for the challenges.”

Barber credits much of his accomplishments to those who connected him to opportunities, including Vanderkluysen and other researchers, Meredith Wooten, PhD, in Drexel’s Fellowships Office, as well as staff in Drexel’s Office of Undergraduate Research. Barber’s work with Vanderkluysen over the past three years, first as a student volunteer and later through independent research and research co-ops, formed the centerpiece of his Hollings application.

“Ever since I started working on research with Dr. Vanderkluysen, and especially after this summer at Yellowstone and Axial, I’ve fallen in love with volcanology,” Barber says. “The grad programs that I’m looking at are all volcano-centered.”

Barber says his Drexel experiences have also helped him understand the complex relationship between humans and Earth processes, and his own capabilities as a student scholar.

“I really pushed my comfort zone and learned a lot about myself this summer,” he says. “I feel more confident in what I can do as a scientist, and prepared to take on graduate level volcanology research.”

For more information on the NOAA Ernest F. Hollings Undergraduate Scholarship Program, visit the Drexel Fellowships website.

Update (February 2018): Nick Barber was named a 2018 Gates Cambridge Scholar, one of 35 scholars nationwide to be awarded a fully funded graduate degree to the University of Cambridge. Only the second student in Drexel history to receive the distinction, Barber will pursue a PhD in Earth Science focusing on the behavior of trace metals in volcanic systems. Congratulations Nick!