The Impact of COVID-19 in Latino Communities in Philadelphia

Data Brief

June 2021

DISPROPORTIONATE TOLL

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the loss of many lives in Philadelphia. The impact, however, has been disproportionately high among Latino and Black communities. Over the past year, excess rates of infection, hospitalization and deaths have unfolded among the Latino community. In this brief, we use the framework of differential exposure and vulnerability to illustrate the context in which factors have converged to result in disproportionately large COVID-19 impact among Latinos in Philadelphia.

PHILADELPHIA'S LATINO POPULATION

Latinos in Philadelphia represent a large and diverse population with respect to ancestry and their migration status. In 2014-2018, around 15% of the population in Philadelphia self-identified as Hispanic or Latino. One in five Latinos living in Philadelphia was born outside of the US. More than 60% of Latinos in Philadelphia have Puerto Rican ancestry, followed by 12% with Dominican ancestry. Latinos with ancestry in Mexico or countries in Central America are around 8% and 7% respectively. Latinos are concentrated in North Philadelphia, where most of the Latinos with Puerto Rican or Dominican ancestry reside, and in South Philadelphia, where most of the Latinos with Mexican or Central American ancestry reside.

Value above bar is the relative difference in hospitalization or mortality rates among Blacks or Latinos vs. non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 1: Disparities in age-stratified COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality in Philadelphia, PDPH (by 1/26/21)

Juan, 38 years old, has been working doing home repairs since he moved from Puerto Rico to Philadelphia

2 years ago. He knows little English, just enough to get by. His low salary and the need to support his parents back in Puerto Rico make it impossible to afford living by himself. He rents a room in a house, where he shares common spaces with another family. As a consequence of the pandemic his hours doing home repairs have been cut. While at work, he has tried to comply with Health Department guidelines to reduce exposure. In the past couple of days some of his coworkers started getting sick. Despite experiencing very mild initial symptoms himself, he tried to get tested to avoid exposing others. Due to language barriers and lack of knowledge of the healthcare system, he had trouble finding a place to get tested.

Juan does not have savings, or get paid time off. While symptoms were mild, he continued to work, but one day he woke up with a strong pressure in his chest and difficulty breathing. One of his roommates called an ambulance. Juan was hospitalized and diagnosed with COVID-19.

RACIAL/ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN COVID-19

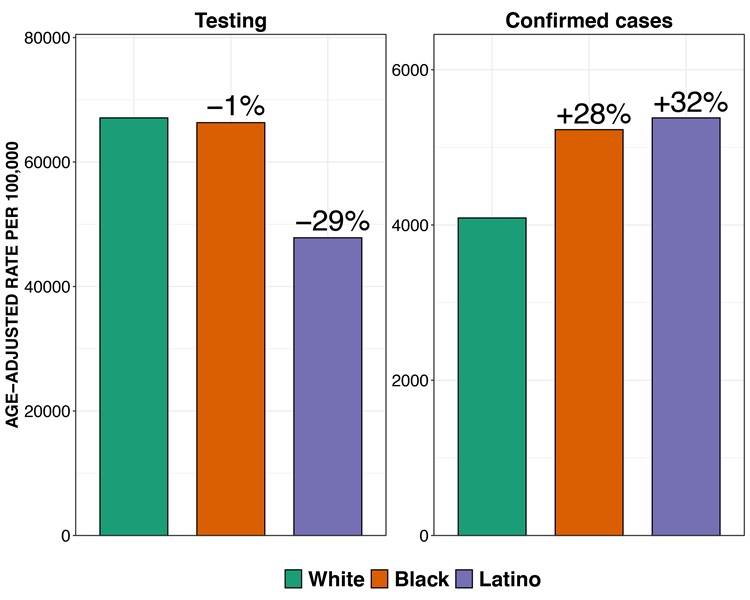

Because the Philadelphia Latino population is younger than other groups, comparisons within age groups, or age-adjusted data are needed to accurately show disparities. In every age group, hospitalization and mortality rates are highest amongst Latinos and Blacks (see Figure 1). Latinos have also a 32% higher age-adjusted incidence rate compared to Non-Hispanic (NH) whites, but a 29% lower testing rate. The lower testing rates but higher incidence seen in the Latino population raise concern that infections may be underestimated for this group (see Figure 2). These disparities are not unique to Philadelphia. As the Drexel COVID-19 Inequities Dashboard shows (www.covid-inequities.info), Latinos have some of the highest incidences of COVID-19 across several cities in the nation.

Figure 2: Disparities in age-adjusted COVID-19 testing and incidence rate in Philadelphia, PDPH (by 1/26/21). Age-adjusted using the 2000 US standard population.

Figure 3 shows the spatial distribution of Latinos, social vulnerability (according to CDC's Social Vulnerability Index) and COVID-19 positivity. Neighborhoods with the highest concentration of Latinos also have a much higher positivity ratio (a marker of inadequate access to testing), which further suggests additional barriers to testing.

Figure 3: Spatial distribution of Latinos, social vulnerability, and COVID-19 positivity (cumulatively through 1/26/21) in Philadelphia ACS 2014-2018

DISPARITIES IN COVID-19 EXPOSURES

As shown in Figure 4, some of these disparities may arise because of higher risk of exposures among Latinos or because of differential vulnerability to infection and severe disease.

Figure 4: Sources of disparities in COVID-19

Occupation: In Philadelphia, 32% of Latino workers are employed in essential occupations, as compared to 23% of white workers (see Table 1). Among Latino immigrants, undocumented immigrants are disproportionately employed in jobs with greater transmission risk, such as janitorial services and domestic labor. Around 37% of Latinos in Philadelphia live in poverty, compared to 15% of whites. With limited access to relief funds or unemployment insurance, many Latinos have experienced greater pressure to continue to work and risk occupational exposures than their White counterparts.

Overcrowding: Partly due to economic reasons, Latinos are also far more likely to live in overcrowded (5.3% vs. 1.6%, with 11% of non-citizen Latinos living in overcrowding) and multigenerational households (51% compared to 28%) than whites, respectively (see Table 1). These housing conditions impede self-isolation once one person in the household is infected and increase the risk of exposure to COVID-19 of other household residents including elderly family members.

Transportation: Latinos in Philadelphia are less likely to own a private vehicle (31% do not own a vehicle, as compared to 22% among whites). Some Latinos, particularly those employed at meatpacking plants and in landscaping, are transported to and from work via vans provided by their employers or have to rely on rides by coworkers or family members. Pennsylvania is one of many states that do not grant driver’s licenses to unauthorized immigrants. Thus, economic and legal factors force many Latinos to rely on public transit or carpooling to go to work and carry out daily activities. Lack of access to a private vehicle also may represent a barrier to accessing COVID-19 related testing and healthcare.

Table 1: Socioeconomic characteristics of non-Hispanic white and Latino individual households in Philadelphia

DISPARITIES IN VULNERABILITY TO THE EFFECTS OF COVID-19

Differential vulnerability refers to the different effects that the same exposures have across minorities. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a double burden of vulnerability: (1) vulnerability to the disease itself (e.g., severe disease) and (2) vulnerability to the impact of the pandemic (e.g., employment loss). Underlying social conditions lead to a concentration of risk factors and potential amplification of their effects on the likelihood of severe disease. Without social safety nets such as universal health coverage or unemployment insurance, the direct costs of health care and lost income due to unemployment, furlough, or disease are absorbed by individuals and their families.

Comorbidities: Latino residents of Philadelphia have a disproportionately higher prevalence of risk factors that confer a higher risk of severe COVID-19, which in 2018-2019 notably included obesity (43% vs 26% among NH whites)and conditions that compromise immune response such as HIV (45.8 per 100,000, vs 13.9 among NH whites).

Barriers to access to healthcare: Language, citizenship status, and immigration law enforcement greatly limit access to care and barriers

to health insurance remain despite the Affordable Care Act. While 16% of Philadelphia Latinos lack health insurance, this barrier to care is even greater among those born out of the US (60% are uninsured). Moreover, Latinos face further disparities in access to high quality, culturally and linguistically appropriate medical care, especially for those who are foreign born, poor, or undocumented. Beyond health insurance and language related barriers, other barriers faced by many Latinos include limited paid sick leave, and competing household demands (e.g., childcare). Latinos in Philadelphia are 2.3 times more likely to not have a primary care provider, and 62% more likely to forgo care due to costs, as compared to NH whites.

Vulnerability to economic crises and school closures: By

May 2020, 9.9% of Latino workers were receiving unemployment assistance, much higher than the pre-pandemic proportion 1.5%.

Given that undocumented immigrants have been largely excluded

from federal relief measures, the true economic impact may be largely underestimated for this group. Latino households in Philadelphia are less likely to own a computer or have access to broadband internet than white households, making remote learning for children in the context of school closures more challenging (see Table 1).

Rosa María, 35 years old, is a single mother from Guatemala who is only fluent in Spanish. She has two children, lives in a house with two other families, is the sole income earner in her family, and has no childcare options beyond their public school, which is only conducting remote learning. After living for ten years in the US, she has been unable to acquire a green card or any other legal status permit.

She is currently uninsured as the cost of a private insurance program was unaffordable while working as a dish washer and cleaner in a restaurant. Insurance is even further out of reach now that she has lost her job due to the pandemic. She is not eligible for public insurance programs or for relief funds, even though she has been paying taxes using an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN) for many years. Other members of the household started getting sick, but isolating became challenging with several families living in the same house.

When Rosa started experiencing symptoms, she did not know where to get tested and felt scared to consult with health services, since she has heard of the attempted ‘medical deportation’ of a Guatemalan immigrant in June of 2020 by a large hospital system in Philadelphia. When she sought medical services in the past, she always took her children with her and they helped her translate, but this is no longer a possibility. Rosa and the other members of her family, unable to get tested, assumed being infected and stayed home. Fortunately, all were young and healthy, and none developed severe disease.

RESPONSE TO THE PANDEMIC

Multiple efforts and initiatives have been implemented in Philadelphia to reduce the impact of COVID-19 and reduce COVID-19 burdens on Latinos and other racial/ethnic groups. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health, in concert with other departments with the City of Philadelphia, Latino-serving community-based organizations, the local health care systems, and academic partners have embarked on significant multi-pronged efforts including the following:

Development and dissemination of Spanish-speaking information about safety measures, and mass media campaigns about mask use and testing and vaccination sites.

Started reporting data of COVID-19 outcomes and testing by race/ethnicity, including Latino as specific category, and age, before such data was standard and widely available.

Partnership with Latino-Serving organizations to expand testing and to provide supporting services (e.g., food, benefits applications, etc.) and particularly among Latino populations at the highest risk (e.g., undocumented, uninsured, etc.).

Development of policies and guidance for workplaces to reduce risk of COVID-19 transmission, including reopening guidance specifically for undocumented workers and families.

Dissemination of information regarding worker protections for essential workers.

Implementation of multi-lingual, multi-cultural contact tracing program, operated partly by bilingual English/Spanish Latino staff.

Partnerships with COMCAST, the main local Internet provider, to develop PHL Connected, a plan to expand Internet access to every Philadelphia resident, regardless of income and migration status.

Development and dissemination of a formal Coronavirus Racial Equity Plan, which includes Latino community representatives and advocates, with concrete metrics to track progress.

There has been a mobilization and promotion of partnerships and interagency collaborations across Latino-serving organizations through a variety of efforts and facilitated by academic institutions. For example, faculty of the Drexel, Dornsife School of Public Health convened meetings open to representatives from the Department of Public Health, the Office of Immigrant Affairs, and local Latino-serving organizations representing health, social, legal, and government sectors. Through regular town halls, this Latino Health Collective has been identifying the most pressing COVID-19 needs at the community- and organization-level, sharing information, and leveraging resources to respond to these needs. Importantly, the Collective has facilitated partnerships and efforts pursued by Latino-serving organizations to access and distribute relief funds, establish COVID-19 testing sites in Latino neighborhoods, implement food distribution programs, obtain personal protective equipment, and increase their capacity to serve Latino residents through the pandemic.

Granted, these efforts have not been sufficient to eliminate the persistent health and security threats faced by Latinos due to COVID-19 and much work is still needed to reduce the unequal impact of the pandemic on this population. As the

city embarks on the daunting task of vaccinating every eligible person in Philadelphia for COVID-19, there is a need to continue to identify and implement effective strategies to ensure equitable access to vaccines for Latinos and other racial/ ethnic minorities disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and its aftermath in Philadelphia.

The COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Philadelphia began December 2020. As of May 20th, 2021, 50% and 60% of white and Asian residents have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared to 30% of Latino and Black residents. City-led efforts to increase vaccine distribution among Latinos and other minorities have included the participation of the Coronavirus Racial Equity Task Force in the City Vaccine Advisory Group and the setup of a FEMA site at the Esperanza Center. The City has also established partnerships with trusted, community-based organizations to set up permanent vaccination clinics or pop-up vaccination events at their premises to increase availability and access to vaccination among Latino communities. However, the persistent disparities in vaccination indicate that more work needs to be done to improve access and reduce barriers among these communities.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Latino communities in Philadelphia have been disproportionately affected by both the public health and the social components of this pandemic. The Latino population of Philadelphia has seen some of the highest incidence, hospitalization, and mortality rates of all racial/ethnic groups in the city, and have had the lowest rates of testing. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health, together with multiple partners of the community responded decisively and earnestly to address the needs of the Latino population. However, disparities have remained which suggest that additional efforts will be needed to address the fundamental drivers of differential exposures and vulnerability levels:

During the COVID-19 pandemic

Continue to increase access and resources available for testing, treatment, and vaccination at trusted Latino organizations in the community, especially those who serve undocumented immigrants.

Expand the reach of isolation programs, especially for individuals living in overcrowded households.

Ensure access to free personal protective equipment for all frontline workers.

Expand eligibility criteria for any future federal relief measures to ensure accessibility across to the entire population, including undocumented workers.

Given the disproportionate impact that school closures have on racial, ethnic, and immigrant communities, identifying and implementing measures to reopen public schools must be a priority.

Expand social safety net measures: continue eviction moratorium, increase cash transfer programs and unemployment insurance programs regardless of migration status.

Suspend arrests by ICE and deportations of immigrants, end public charge rule, as these practices instill fear and avoidant behaviors that counteract directly pandemic mitigation efforts.

Continue to work to close digital and education gaps, especially for limited English proficient families with school-aged children.

During and beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic

Implement universal healthcare coverage, free at the point of care, ensure that access and coverage is not limited by immigration status.

Improve labor protections (paid sick leave, increasing minimum wage, workers’ rights), especially for workers that are exempt from current regulations (farm and domestic), who are disproportionately Latino.

Allow unauthorized immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses so limitations associated with reliance with public transportation can be diminished.

Reform the immigration system following a model for labor migration that prioritizes human rights of immigrants and their families and elevates labor standards for all workers.

REFERENCES AND OTHER RESOURCES

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Testing and data. URL: https://www.phila.gov/programs/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/testing-and-data/#/

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Impact by Age and Race/Ethnicity in Philadelphia. CHART 2020; 5(7):1-5. https://www.phila.gov/media/20200918100441/CHARTv5e7_revise.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. AIDS Activities Coordinating Office Surveillance Report, 2017. URL: https://www.phila.gov/media/20190130165248/HIVSurveillanceReport_2017_Web_Version.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Access to Primary Care in Philadelphia. PDPH Chart Dec 2019, 4(8) https://www.phila.gov/media/20191218101940/CHART-v4e8.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2020. Health of the City. Philadelphia’s Community Health Assessment. https://www.phila.gov/media/20201230141933/HealthOfTheCity-2020.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. July 2020. Coronavirus-Interim-Racial-Equity-Plan. https://www.phila.gov/media/20200727145003/Coronavirus-Interim-Racial-Equity-Plan_revise.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Unemployment and mortality in Philadelphia. PDPH Chart February 2021, 6(3) https://www.phila.gov/media/20210216093428/CHARTv6e3.pdf

- National Conference of State Legislatures. COVID-19 and Immigrants. URL: https://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/covid-19-and-immigrants.aspx

- Pew Research Center. Economic Fallout From COVID-19 Continues To Hit Lower-Income Americans the Hardest. URL: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/09/24/economic-fallout-from-covid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/

- Pew Research Center. Mexicans decline to less than half the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population for the first time. URL: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/us-unauthorized-immigrant-population-2017/

- Centro de los Derechos del Migrante. Ripe for Reform. URL: https://cdmigrante.org/ripe-for-reform/

- Center for American Progress. Protecting Undocumented Workers on the Pandemic’s Front Lines. URL: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2020/12/02/493307/protecting-undocumented-workers-pandemics-front-lines/

- Center for American Progress. Congress Must Strengthen SNAP To Support Essential Workers During the Coronavirus Crisis. URL: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/news/2020/06/11/486187/congress-must-strengthen-snap-support-essential-workers-coronavirus-crisis/

- Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the Unauthorized Population. URL: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/PA

- Evans T, Whitehead M, Bhuiya A, Diderichsen F, Wirth M. Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action. Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Blumenshine P, Reingold A, Egerter S, Mockenhaupt R, Braveman P, Marks J. Pandemic Influenza Planning in the United States from a Health Disparities Perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(5):709-715. doi:10.3201/eid1405.071301

CITATION

Lazo M, Bilal U, Correa C, Furukawa A, Martinez-Donate A, Zumaeta-Castillo C. The Impact of COVID-19 in Latino Communities in Philadelphia. Drexel University Urban Health Collaborative; June 2021.