Drug Overdose Deaths in Big Cities

Download the Brief

August 2022

Overview

This brief uses data on overdose deaths from the Big Cities Health Inventory (BCHI) data platform. Data are shown for the 35 member cities in the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC).

Figure 1: Drug overdose death rate in BCHC cities, 2020 (per 100,000 population, age-adjusted).

In 2020, total drug overdose deaths ranged from 14 to 120 deaths per 100,000 population. The average death rate across BCHC cities (37.1 per 100,000) was much higher than the national rate (21.6 per 100,000).

Increase in Overdose Deaths and in Opioid-involved Deaths in BCHC Cities

Between 2010 and 2020, drug overdose deaths in BCHC cities nearly tripled with the largest increase between 2019 and 2020. Recent increases in overdose deaths can be attributed to replacement of prescription opioids and heroin with highly potent illicit synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, as well as increases in polysubstance use (use of opioids along with stimulant drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine).

Figure 2: Number of drug overdose deaths among all BCHC cities, with insert bar representing number of deaths involving opioids, 2010-2020.

By 2020, at least 74% of overdose deaths involved opioids (up from 54% in 2010).

In 2020, across BCHC cities approximately 40 fatal overdoses occurred every day.

Overdose Deaths by Gender in BCHC Cities

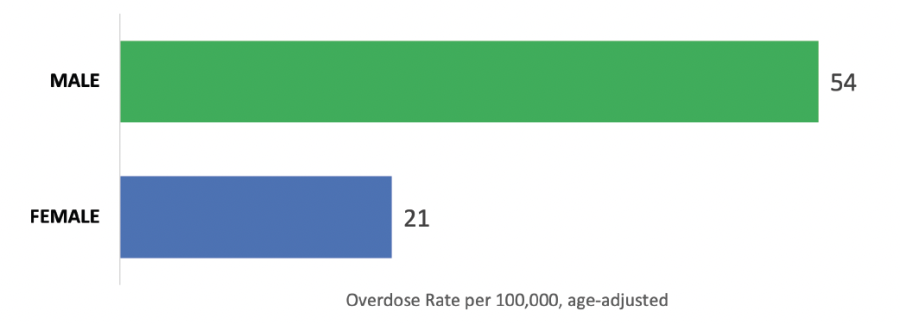

Figure 3: Drug overdose death rate, by gender, averaged across BCHC cities, 2020 (per 100,000 population, age-adjusted).

The overdose death rate for men was more than twice as high as for women (in 2020, 54 per 100,000 males vs. 21 per 100,000 females, age-adjusted).

Overdose Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in BCHC Cities

In 2010, white persons had the highest drug overdose death rate yet by 2020 Black persons had the highest rate (see Figure 4). The rise in overdose deaths among Black persons is thought to be rooted in three inter-related factors: 1) racism in healthcare where Black patients were not prescribed opioids for similar levels of pain that white patients experienced, 2) the rapid rise in illicit synthetic street opioids (and mix of drugs) which are more lethal than heroin, and 3) systematically lower access to health care treatment options for Black persons.In 2010, white persons had the highest drug overdose death rate, yet by 2020 Black persons had the highest rate. The rise in overdose deaths among Black persons relative to white persons is thought to be rooted in inter-related factors that implicate structural racism in healthcare access and treatment. The first factors relate to racism in opioid prescribing practices namely, that for similar levels of pain, Black patients have been prescribed opioids at much lower doses (or not at all). Lower opioid prescriptions to Black patients partially protected them during the early period of the opioid epidemic that was fueled by over-prescribing; however, it also contributed to Black persons being disproportionately reliant on street drug supplies. In recent years, drugs that are more lethal than heroin (e.g., illicit synthetic opioids and mixtures of drugs) have dominated the street drug supply, thereby particularly affecting Black drug users. Finally, Black drug users have systematically lower access to early intervention and health care treatment for addiction.

Figure 4: Drug overdose death rate, by race and ethnicity, averaged across BCHC cities, 2010 and 2020 (per 100,000 population, age-adjusted).

Between 2010 and 2020, drug overdose death rates increased within all races/ethnicities. By 2020 Black persons had the highest rate (55.8 per 100,000 Black persons).

Solutions and Advocacy

While federal policy discussion and funding has been focused on the nation’s rural areas, overdose deaths in the nation’s largest cities have spiked in recent years. Big city public health officials are on the front lines of the drug overdose epidemic, working to reduce harms to health from drug use. Health officials have advocated for enhanced resources and federal policy changes including decriminalization of addiction and supporting trauma-informed harm reduction programming. The harm reduction model aims to save lives and prevent infectious disease by reducing stigma around addiction, acknowledge drug user’s individual autonomy and dignity, embed health-related services into safer-drug-use programming, and improve access to addiction treatment. For more on the BCHC’s policy initiatives see here.

About the Data Platform

Since 2019, the Big Cities Health Inventory (BCHI) data platform has been maintained by the Drexel Urban Health Collaborative (UHC) at the Dornsife School of Public Health in partnership with Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC). Visitors

to the data platform can explore metrics, view data charts by city, select multiple cities for comparison, and download charts and data. Visit the BCHI data platform (bigcitieshealthdata.org) to learn more.

The BCHI data platform is primarily funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through a cooperative agreement with the National Association of County and City Health Officials. The views expressed in this brief do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

BCHC and UHC Partnership

The Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC) is a forum for the lead health officials of America’s largest metropolitan health departments to exchange strategies and jointly address issues to promote the health and safety of more than 61 million

people they serve. The Drexel Urban Health Collaborative (UHC) has partnered with BCHC to support the Coalition’s vision of healthy, more equitable cities through big city innovation and leadership. The UHC is a multidisciplinary research and practice center that leverages the power of data, research, education, and partnerships to make cities healthier, more equitable, and environmentally sustainable.

Citation

Niamatullah, S., Auchincloss, A., Livengood, K. (2022). Drug Overdose Deaths in Big Cities. Drexel University, Urban Health Collaborative. Philadelphia, PA.