On Billionaires and Trillionaires

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

March 5, 2020

It’s hard to avoid the topic of billionaires in Democratic politics these days. Senator Sanders has focused on the 400 wealthiest people who together control $2.9 trillion to justify his agenda of broadly expanding the welfare state. Senator Warren on the other hand, has proposed a wealth tax on households worth more than half-a-billion which would raise $3.25 trillion of federal revenue over the next decade. Vice President Biden, the frontrunner after Super Tuesday, shows less outright hostility to billionaires. Nonetheless, his proposal for raising revenue is similarly oriented to those of Warren and Sanders in focusing on taxing wealth rather than work (especially through capital gain tax increases and closing foreign tax havens).

The exclusive focus on taxation diverts attention from another worthy topic in our view: where vast amounts of private capital invest in the United States.

Back in January we wrote about a number of public and private institutional investors, led by C40 Cities and BlackRock, that were beginning to examine their investment decisions –– divesting from fossil fuels and investing in the clean economy. This prompted us to examine state and local public pensions in the US generally. These are unique pools of capital, where public and private aims (and assets) are intertwined.

Public pensions (and all pensions really) should be part of the “good” money in America’s financial system. When their investments do well, this money supports the long term economic security of the 137 million Americans with pensions. These are firefighters, law enforcement officers, public school teachers, manufacturing and construction workers, and white-collar professionals –– i.e., the people whose livelihoods progressives seek to support through their policies.

As of the most recent measure in 2019, there are $23.8 trillion of assets in American pensions. Just under twenty percent of these assets ($4.57 trillion) are from state and local public pensions.

Employees rarely invest their own pensions. They instead rely on governing entities –– like public pension boards or State Treasurers in the case of state and local pensions –– that are obligated through their fiduciary duties to invest in a way that’s within the interest of employees (i.e. seek market rate returns).

These entities, in turn, delegate to asset managers where to invest. Because of this, our hunch is that most state and local pensions –– like most pillars of local wealth –– are disproportionately invested in alpha cities, particularly on the coasts. Our work with Opportunity Zones has made it evident to us that most wealth in smaller cities and the middle of the country is invested outside its region –– even as many rich economic assets exist locally. This wealth export industry has been facilitated by a similar network of players to those which public pensions delegate their investment decisions (many of which have narrow definitions of where and what to invest in).

We should be abundantly clear that we’re not suggesting that public pensions suddenly accept lower returns or make politically motivated investments to invest in local projects. Rather, we’re suggesting that there may be investments that meet public pension return profiles that also meet social goals (instead of exporting wealth from the community).

But given the money at stake, and the potentially salutary politics and economics, why are progressives not focusing more on public pension investment?

Partially it’s because understanding the full potential requires understanding where public pensions are currently invested. This, it turns out, is exceedingly difficult.

Although we could easily find the asset classes of public pension investments, without proprietary data it’s next to impossible to find out what these holdings are. This is astonishingly low transparency around public pension holdings.

Our theory is that this lack of transparency comes from three different places:

- The serious pension underfunding crisis: When America’s public pensions are examined, most emphasis is on the changing nature of their benefit plans, their unfunded liabilities, or politically salacious “pay-to-play” scandals. These are each vital focal points –– currently t’s estimated that there’s a $1 trillion funding gap in state and local pension liabilities. However, the result of this focus is that less attention is paid to where public pensions are investing.

- A focus on asset classes rather than holdings: Even when public pension investments are examined, research focuses on asset classes and not the specific holdings within these classes. This research often traces the rise in pensions’ alternative investments (private equity, hedge funds, and real estate). While important, it doesn’t tell us what projects or geographies this money is supporting.

- Delegation & lack of capacity breed ambiguity: The chronic underfunding of public pensions since the Great Recession has fed an increased pressure to generate higher returns through alternative investments rather than a typical stock and bond portfolio. In response, the management of public pension assets has increasingly been delegated to private asset managers (like Blackstone, BlackRock, the Carlyle Group, etc.) who, in turn, often invest in funds-of-funds and indexes.

The net result of these trends means that taking stock of a specific public pension’s holdings at any given time requires asking state and local officials to ask their asset managers where they’re invested. This is, to put it mildly, not especially transparent. To be clear, there’s a very real pressure driving each factor. Public pensions are caught in a tight bind between fiduciary obligations, low interest rates, and underfunding. This means that making any policy change can be politically difficult.

That’s the bad news.

Emerging models

The good news is that there are some promising new models emerging for transparent and targeted investments –– that leverage the financial system for progressive aims. In 2016, the US Department of Labor issued new guidance that allowed pensions to consider social and environmental impacts within their fiduciary responsibilities. As of the last measurement in 2017, there are $68.8 billion (or approximately one Mike Bloomberg’s worth) of pensions active in these Economically Targeted Investments — although data is partial. About 80% of these investments are partially or completely composed of state and local public pension money. These assets are targeted across geography (e.g., state-focused and underserved markets) and sectors like community development, business financing, affordable housing and microfinance.

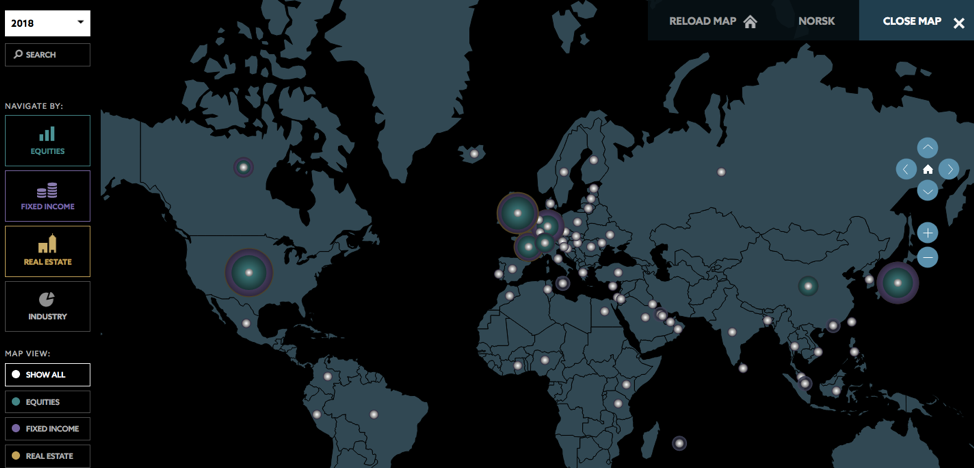

Yet even these focus areas tell us little about what the pensions are actually holding. For this type of transparency, we find Norway’s Sovereign wealth fund to be the gold standard. This fund is, uncoincidentally, a leading model of fossil fuel divestment. But it also has a top-notch transparency tool that enables the public to see its specific holdings by asset class, sector, and geography.

Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, a model in transparency

Now, there are obviously differences between a national sovereign wealth fund and local school teachers’ pensions. For one, the funding source and fiduciary goals slightly differ.

Yet as we develop a broader project following the good money, Norway’s model raises a question: why can’t we have a similar level of investment transparency for America’s state and local public pensions?

If done right, we believe that public pension investments in place can unlock a virtuous cycle that builds community wealth by investing strategically in places. We see increased transparency on holdings as one way start a conversation to answer the question of where, in fact, the good money has gone.

At the very least, we hope it puts trillions of dollars — and even a Scandinavian model — back in the sights of progressive policy discussion.

This is part of an emerging project on public pension investment practices — and we’re still refining our ideas — we’d love to hear your thoughts.

Colin Higgins is program director at The Governance Project