From Federal Sources to Local Uses: Maximizing the American Rescue Plan from the Ground Up

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

April 2, 2021

(co-authored with Colin Higgins, Karyn Bruggeman, Victoria Orozco and Paige Sterling)

On March 11, President Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP) into law. The legislation makes historic investments intended to steer people and places across the country out of the worst economic and public health shock in a hundred years. It strives to make the large-scale impact that the moment demands. To do so, though, the federal government must harness the full capacities of local state, city, and county governments. As we move from policy design to deployment of the ARP, cities and counties must be in the driver’s seat.

Put simply: local leaders must first understand the totality of federal sources in the American Rescue Plan and in short order establish a clear set of local uses to drive the deployment of these funds.

While the media’s attention has been directed at the flexible funds cities and counties will receive, local leaders must understand and utilize the full array of federal resources at their disposal to maximize the ARP’s impact. This means understanding who in the city, county or state will decide how federal funding can be allocated or activated and what must be done to deploy funds for common aims and long-term capacity building. Earlier in March, we laid out five principles for ARP fund deployment to ensure the package is greater than the sum of its parts.

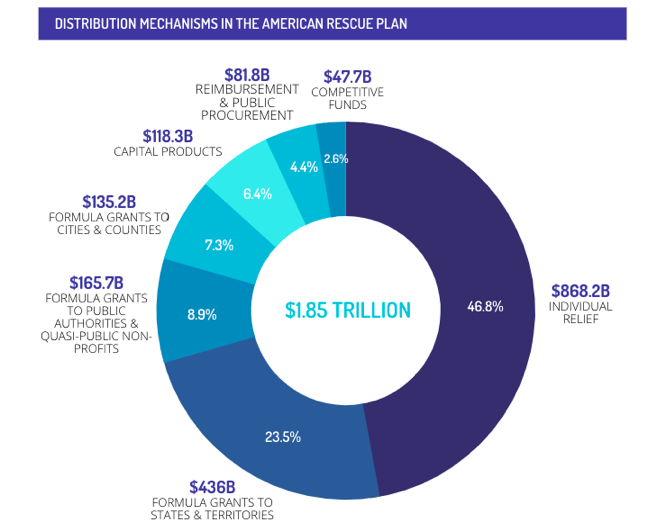

The Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University has created the American Rescue Plan Federal Investment Guide and a database to accompany it with our partners at Accelerator for America and the U.S. Conference of Mayors as the first step towards operationalizing these principles. This document catalogues $1.85 trillion of investments over 84 unique programs that will receive ARP money, distributed across 19 federal agencies. More than half of the programs are distributed through three agencies — the Departments of Treasury, Health and Human Services and Agriculture. Each program involves different funding products distributed through different channels to a unique combination of governments, institutions, businesses, and individuals.

In short, this bill is large and complex. City Halls and County executives will play many different roles in delivering funding streams within the bill –program manager, grant applicant, coordinator, collaborator, and communicator– depending on how investments reach a program’s intended recipients. To simplify this otherwise complicated package for local leaders, we categorized federal investment using three criteria. These criteria are action-oriented and approach the ARP from the bottom-up, i.e., taking the perspective of local public, private and sector actors who are actually tasked with delivery:

- Distribution: This criterion focuses on how the funds move out of their sources in federal agencies (e.g., by an established formula? through the tax code? through a competitive grant application?). The details of these distribution mechanisms determine the processes for accessing federal funds and, relatedly, how quickly investments can be expected.

- Decision making: This criterion focuses on the institutions and entities that receive the funding, or which must apply. This has significant bearing on who must be engaged in order to guide a holistic recovery, since the recipient of the funds have a large amount of discretion over spending. For example, school districts will receive a large investment from the ARP for summer school and infrastructure improvements; using these funds to drive inclusive outcomes (e.g., growing the supply of diverse vendors) will require close coordination with Mayors, entrepreneurial support organizations and financial institutions.

- Deployment: This criterion focuses on how funds move into their final end-uses (e.g., how soon must the funding be spent? what clear red lines are drawn for ineligible uses? what are the application windows and requirements for competitive funds?). The variability in specific requirements for funding products must be untangled in order to deploy the investments in a time-sequenced, non-duplicative, and holistic way. We provide a dynamic database alongside the Investment Guide to allow local leaders to easily sort through the funds so they can maximize their deployment.

These criteria lead us to organize the ARP into seven categories that reflect how federal funds will reach local communities. This approach differs from the national media coverage to date, which has approached the ARP by agency-defined issue-area (a siloed approach that often doesn’t align with the way cities and metros operate). The Federal Investment Guide’s seven categories strive to make sense of the ARP in a way that supports local action:

- Individual Relief ($868.2 B): These funds are distributed to individuals or individual firms through the tax code or a public system. Some funds are distributed automatically; others require an application. They constitute the bulk of the ARP (e.g., $1,400 payments, Child Tax Credit, unemployment insurance).

- Formula Funds to States & Territories ($436 B): These funds are distributed to state and territorial government accounts through existing federal formulas. They are then formulaically or competitively allocated to local governments, non-profits, or private organizations (e.g., Child Care and Development Block Grant funds, Title I Funds for schools, Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) funding).

- Formula Funds to Public Authorities & Quasi-Public Non-profits ($165.7 B): These funds are distributed through existing federal formulas to designated entities that operate adjacent to the state, city, or county government but do not immediately answer to the government executive (e.g., public transit funds, Airport Improvement Program funds, Section 8 voucher funding)

- Formula Funds to Cities & Counties ($135.2): These funds are distributed to city and county general purpose governments through federal formulas.

- Capital Products ($118.3 B): These funds are provided by the federal government mostly as a loan, a guarantee, or a credit enhancement that encourages private capital markets to achieve a desired policy aim (e.g., Paycheck Protection Program, State Small Business Credit Initiative).

- Reimbursement & Public Procurement ($81.8 B): These funds are distributed through a reimbursement application or competitive bid by the federal government. They require eligible businesses, individuals, or other units of government to apply (e.g., FEMA disaster reimbursement, Commodity Credit Corporation purchases, AmeriCorps hiring).

- Competitive Funds ($47.7 B): These funds are capped and public, private, or non-profit organizations must apply within a certain timeframe. Their applications will be evaluated along certain criteria (e.g., EDA economic adjustment assistance grants, USDA community facilities grants).

Note: because we are predominantly focused on federal-to-local funding streams that reach cities and their residents this chart includes all funding in the ARP except appropriations to Tribal Governments or Agency appropriations focused on program operations at the federal level with no further sub-allocation. All amounts are rounded to the nearest decimal point (the nearest hundred million).

The key point that emerges from this categorization is that there are a wide variety of pathways to braid and blend together public investments in the ARP (to say nothing of the private or philanthropic investments these can leverage). The flexible funding received directly by cities and counties is a relatively small portion of the package that’s received a large amount of attention. But there is nearly $900 billion — larger than all of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act! — remaining once individual relief and flexible city and county funds have been accounted for. Cities and counties must develop a vision for how they want to use the rest of the money — otherwise, we fear that it may amount to a missed opportunity.

Next Steps: Connecting Local Uses to Federal Sources

We have three suggested next steps for local leaders who are urgently trying to make sense of the ARP and deploy it to serve the un-ending amount of local needs facing them.

1. Try to solve something well, don’t try to solve everything

The ARP is a large plan, but it could be spread very thin across a set of uncoordinated priorities and actors on the local level. With the sheer amount and variety of federal funding it is tempting for local leaders to get overwhelmed. It is equally tempting to try and focus on pulling down every last bit of federal funding from every nook-and-cranny of the federal government. With limited staff time and unlimited local needs, this is a recipe for failure.

Rather than trying to do everything, local leaders should establish a clear set of three-to-five priority goals they hope to achieve with ARP funding. These can draw from previous strategic plans or gap assessments that emerged from the crises of the past year. Priorities can take a wide variety of forms: dramatically increasing the number, size, and sector of Black-, Latino- and Asian-owned businesses; increasing affordable housing stock and addressing the rise in homelessness; building neighborhood community wealth as cities emerge from the pandemic; stabilizing downtown business districts; decreasing health inequities across the city; and the list goes on.

The key point is that local leaders must pick a few priorities to focus on and then design, fund, and execute strategies well. This will also aid in communicating the impact of the ARP locally.

2. Once you have clear priorities, connect local uses to federal sources

The beauty of the ARP is that it has a wide array of flexible investments — and even more investments that, while less-flexible, can be leveraged to achieve local goals. The challenge with the ARP is that there is so much in it that it is easy to lose sight of the local North Star (and it is now even easier to lose sight of imminent goals with the recently announced American Jobs Plan).

We think the best way to deploy the ARP is to declare a clearly defined set of local priorities. From these priorities, local leadership should define sub-priorities and end uses. These are the ultimate discrete deliverables that the federal investments will be used for (e.g., using HVAC systems in K-12 schools in the service of a broader plan to equalize education access coming out of the pandemic, for example). Local leaders should then work backwards to connect these local end uses to the federal sources of funds, taking care to engage the key institutions/recipients that the funds will pass through as they move from source to use. Ultimately, this should take the form of a sources and uses spreadsheet.

For example, if a city decides that it wants to prioritize Black-, Latino-, and Asian-owned business growth (which we’ve been writing about as a key cross-cutting priority), they should think about sources and uses in a way that follows the schematic below.

To fund these uses (which would require further specificity), localities would need to examine a wide variety of sources in the ARP. These sources include explicitly designated small business programs run out of the SBA ––like the PPP, Economic Injury Disaster Loans, and the Shuttered Venues fund–– and the agency’s new Community Navigator pilot to fund intermediaries that help individual businesses navigate resources available to them. It would include leveraging capital products, like the State Small Business Credit Initiative, which is administered through state programs and federally funded at nearly 10X its original funding in 2010.

But truly maximizing a vision for MBE business recovery and growth would require thinking about sources more broadly. Operationalizing the small business sources in the ARP could take a variety of forms, including:

- Working with state agencies, local advocates, partners, families, and minority-owned child care providers to align and deploy the Child Care Stabilization Fund and the Child Care and Development Block Grant to upgrade child care supply as demand increases, ensuring an equitable recovery that unlocks opportunities for businesses, especially those run by women of color;

- Working with local arts and humanities organizations in tandem with small business intermediaries to ensure that community cultural organizations and artists receive relief funding through the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities;

- Working with regional economic development intermediaries and the business community to apply for EDA funding to support a broader inclusive entrepreneurship recovery; and

- Working with school districts, local chambers, and MBE construction firms to develop a pipeline of contracts to diverse firms for the series of K-12 school capital projects that are funded through the ARP.

The lesson is clear. As with all things federal, it is best not to judge a program solely by its label or the administering agency. The notion that “small business” received $50 billion in the American Rescue Plan is misleading. Given the flexibility inherent in the legislation and the extent to which multiple programs have the potential to support small businesses, if purposefully and intentionally implemented, the explicit support for small business is clearly a floor, rather than a ceiling.

These are just a few examples of how these funds work for small businesses. But one could undertake a similar exercise for a variety of other priorities. The key is for City Hall and associated stakeholders to develop a clear focus and as soon as possible, drill down into the specific uses of funds so that local leaders can organize a concerted approach to ARP deployment.

3. Convene key actors through Stimulus Command Centers based on priorities

We have previously written that local leaders should establish stimulus command centers to guide the deployment of ARP funding. We are more convinced than ever that such organizing must take hold.

As we’ve had conversations with city leaders across the country it’s become clear that a narrower focus is needed to supercharge these command centers. We believe that Mayors and County executives should convene working groups in stimulus command centers around key local priorities. These working groups ––of recipients of funding, key community stakeholders, civic and business leaders–– can then get to work on establishing clear strategies to draw down and deploy ARP funding in a way that leads to an inclusive recovery.

This modus operandi will serve cities well as the country cycles from rescue to recovery and other forms of funding – for infrastructure, innovation and human capital – are, potentially, authorized and appropriated through subsequent pieces of federal legislation. Such investments will implicate an even broader group of public, private and civic institutions locally as well as offer possibilities for leveraging other sources of capital and expertise. To that end, managing the delivery of the American Rescue Plan now is a dry run for what comes next.

The bottom line: To effectively, efficiently and equitably deploy the ARP, local leaders must develop an action plan with three-to-five clear priority uses and connect these to the wide array of federal sources in the ARP. This will help deploy the funds in locally impactful ways and also clearly communicate the way the package is improving residents’ lives. We have put together the Federal Investment Guide and dynamic ARP database to help in this aim.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Colin Higgins, Karyn Bruggeman and Victoria Orozco are Senior Research Fellows at the Nowak Metro Finance Lab. Paige Sterling is Communications Manager at Accelerator for America.