What's Next on Small Business Relief

Below is the Nowak Metro Finance Lab Newsletter shared biweekly by Bruce Katz.

Sign up to receive these updates.

Five months into the COVID-19 crisis, the outlook for the country’s small businesses is as murky as ever. COVID-19 cases continue to rise across the country, slowing and halting many states’ reopening plans. Even if we were as far along in combatting the virus as we had expected to be in mid-July, small businesses’ path to recovery would be extraordinarily challenging.

The country’s small business problems existed long before COVID hit. America has not been forming new business or increasing economic dynamism at a sufficient rate since the Great Recession. The most recent set of SBA data revealed disturbing trends for Black-owned small business: their share of all employer firms underrepresents the size of the Black population, they are smaller and have lower revenues, and they are highly concentrated in a few sectors. These issues have only become more pronounced due to the coronavirus crisis.

Congress is now, up against impossible deadlines, considering the latest round of small business relief. Mere action is not enough: the correct action is required. If the federal government responds inadequately, there will likely be devastating ripple effects across Main Streets and the broader economy –– suppressing key engines of economic opportunity in distressed communities when they are needed most. If Washington allows entrepreneurship and small business to languish, the country will feel the impacts for generations.

The Senate Republicans put forward the Health, Economic Assistance, Liability Protection and Schools Act (or “HEALS” Act) earlier this week, which gets part of the way to a responsible solution. The Act provides a new Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) loan product: $190 billion of direct appropriation, partially funded by the remaining unused PPP allocation, focused on small businesses with 300 or fewer employees and at least 50% reduction in revenue due to COVID-19, and with expanded eligible expenses.

The Act also proposes new Recovery Sector Loans: $57.7 billion of direct appropriation to guarantee long-term SBA 7(a) loans with improved terms for small businesses in low-income census tracts with 500 or fewer employees and at least 50% reduction in revenue due to COVID. The terms offered are quite favorable: namely a 1 percent interest rate over 20 years and a three-year deferral period before the first payment is due.

Finally, the Act recommends $10 billion for registered Small Business Investment Companies (“SBICs”) that invest in small businesses in low-income census tracts, domestic supply chain manufacturers and businesses with significant COVID-19-related revenue losses.

But the HEALS Act provisions, while an improvement, will not address the special challenges faced by very small and minority-owned businesses. Most importantly, using the SBA’s bank distribution network limits the speed and coverage of relief money. Unbanked and underbanked businesses, which are disproportionately minority-owned, have been less likely to participate in PPP given the program’s reliance on the mainstream banking system. For minority-owned businesses that do have lending relationships and have been able to participate in PPP, discrimination persists. Based on how the fee structure works, banks likely prefer to originate, say, a $5 million loan over a $25,000 loan–a dynamic that disadvantages smaller businesses that are disproportionately minority-owned. And, finally, many very small businesses have short-run non-payroll expenses that exceed the 40% threshold permitted under PPP.

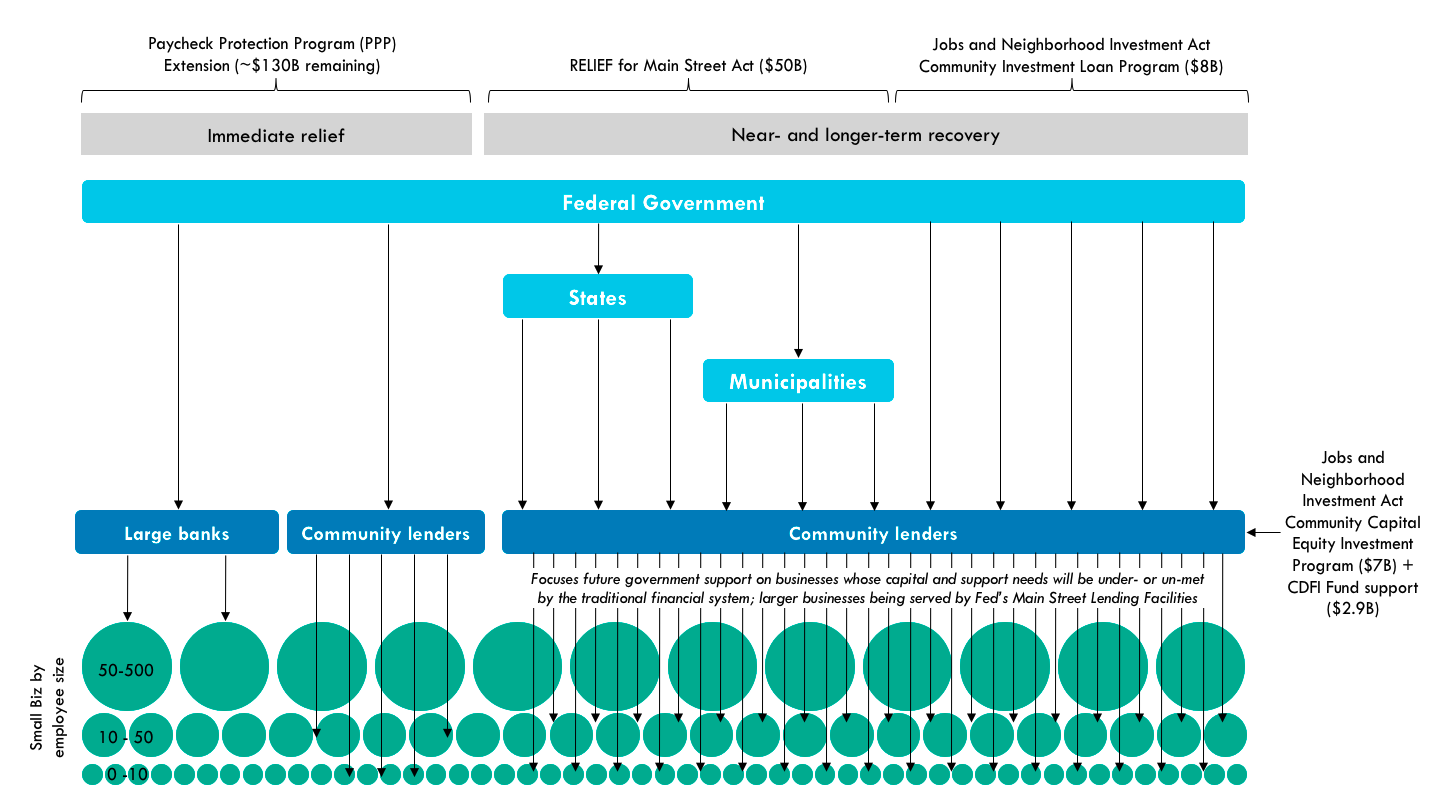

So, what to do? We previously advocated for $50 billion in direct funding to state and local governments with the purpose of targeting the most vulnerable businesses, and have been working with Senators Booker and Daines as they advance the RELIEF for Main Street Act, which has continued to gain bipartisan, bicameral, momentum. The bill builds on local relief efforts that are already actively getting rapid support to businesses. This means that federal resources can piggyback on top of already established efforts. Across the country, states, cities, counties, and towns have established local relief funds to provide emergency support to small businesses impacted by COVID-19. But local efforts are massively oversubscribed. Many funds received requests for more funding than was available within days or even minutes of the applications opening.

We continue to believe that allocating $50 billion via state and local funds remains an essential component of any potential legislative package. The strongest proof of concept possible is the huge variety of states and municipalities that have allocated CARES Act Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) capital to respond to their small business crises. The RELIEF for Main Street Act addresses the structural challenges identified above by offering flexible funds through a capital distribution channel outside the banks. This enables broader and more equitable coverage and faster distribution.

- Local relief funds provide more distribution channels, enabling them to reach a broader set of businesses more quickly and with financing that meets the particular needs of very small businesses unexpectedly on the financial brink, or those attempting to optimize during a slow path to stability.

- Unlike PPP and SBA’s Economic Injury Disaster Loans, which are one-size-fits-all products, local relief funds are able to tailor financing products—primarily through grants but also low-interest loans—to the particular needs of small businesses in their communities.

- Local relief funds encourage local partnerships with entities like community foundations, Black chambers of commerce, and others to ensure high-need businesses are able to participate. Banks like Wells Fargo and Bank of America, or even the SBA, simply aren’t able to do outreach and technical assistance for PPP and EIDL to vulnerable small businesses.

- The RELIEF for Main Street Act also has support across multiple sectors and constituencies. Endorsements include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, International Franchise Association, Small Business Majority, Small Business Roundtable, Page 30 Coalition, Color of Change, Urban League, African American Mayors Association, Economic Innovation Group, the Center for Community Progress, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Coalition, Build from Within Alliance, NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice, Associated Builders and Contractors, and over 100 mayors across the country.

A second proposed bicameral bill ––the Jobs and Neighborhood Reinvestment Act, proposed by Senators Warner, Booker, and Harris, and in the House by Congressman Meeks –– supplements efforts in the RELIEF for Main Street Act, by ensuring that if a state does not have capacity to set up a local fund by itself, federal capital can fill in the gaps. It does so by federally investing in CDFIs and Minority Depository Institutions.

Together, we see the RELIEF for Main Street Act and the Jobs and Neighborhood Reinvestment Act, in combination with PPP reform and a new SBA product, as key to a sound recovery. These bills enable approaches that, as we’ve stressed before, move from distinct financial products to a more holistic place-based approach that focuses on business districts and their neighborhoods, rather than businesses as stand-alone entities. We have proposed that Main Street Regenerators serve as an organizing concept to provide the services needed to combat the problems that will be happening in business districts across the country.

As we show below, together these funds can provide immediate relief and then build to a longer-term recovery that is more equitable and spurs a new cooperative federalism.