Native American Heritage Month: Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte and Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill

November 24, 2020

By Matt Herbison, Drexel Legacy Center Archivist

In recognition of Native American Heritage Month, we focus on two women who graduated from our school over 120 years ago, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte and Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill. Their stories bring historical perspective to two aspects of present-day American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) health care concerns: health disparities in AI/AN communities and the need to create opportunities for medical careers among AI/AN people.

American Indian and Alaska Native Health Care and Health Professionals

American Indian and Alaska Native populations in 2020 face many of the same health care concerns as they have over the last 150 years. It’s a suite of well-recognized problems, enumerated by the National Indian Council on Aging: “Factors such as having a regular source of care, language and communication barriers, lack of diversity in the health care workforce, high rates of poverty, lack of insurance coverage, discrimination against American Indians and Alaska Natives, and large distances from health care services have all added to the disparities that effect American Indian and Alaska Native communities.” (Learn more at nicoa.org/elder-resources/health-disparities/)

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte and Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill earned their MDs late in the 19th century and are often cited as the first and second Native American women to become physicians. Both women recognized that the health care needs of Native Americans in their communities were being neglected. They spent their medical careers providing primary medical care to individuals and families, while advocating for broader support for people on their reservations as well as the surrounding rural populations. Their lives of dedicated service and the battles fought by Drs. Picotte and Minoka-Hill are inspiring, and align strongly with the goals of doctors who serve every type of underserved community throughout history and today. Their stories also speak to a history of racism and assimilation that have long shaped the experiences of Native Americans seeking to balance a combination of identities.

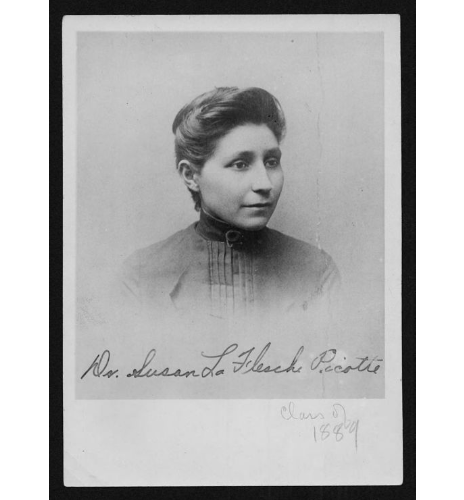

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte, believed to be the first Native American person to earn an MD, graduated in 1889 from one of Drexel College of Medicine’s predecessor schools, Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Dr. Picotte’s father, Joseph LaFlesche, or Iron Eye, was a leader of the Omaha tribe in Nebraska and believed in education as well as assimilation into white society as a path for Native Americans -- a very divisive position among the Omaha. Picotte’s parents encouraged her education at several schools with strong emphasis on assimilating Native Americans into white, European standards of knowledge and culture. Prior to medical school, Picotte attended Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), the historically Black university in Virginia that, at the time, followed a program fashioned on the government-supported Native American boarding schools, designed to "civilize" and "Christianize" Native American students while providing education and practical training.

After graduating second in her class at Hampton Institute, Picotte attended Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. During her time in Philadelphia, she learned the latest medical knowledge and practice while experiencing much of the urban culture of the city. She earned her medical degree in 1889, graduating at the top of her class.

Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania Class of 1889

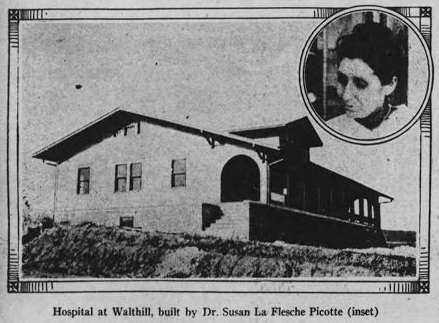

Dr. Picotte practiced in eastern Nebraska for over 20 years, the only physician for many Native Americans in the area as well as for non-Indians living in an area with few doctors. Beyond her medical practice, she spearheaded public health efforts to stem tuberculosis, fight alcoholism, reduce the prevalence of insect-borne diseases and implement sanitation measures. She was also able to use her status as a physician and community leader to expand the rights for the Omaha people, fighting for recognition, self-determination and funding from the state and federal government. Dr. Picotte received financial support for her education and medical practice from government programs and organizations committed to instilling Victorian values in Native Americans. These programs were double-edged; sources of support that allowed Picotte to improve health care among the Indian population also hastened cultural assimilation and conveyed a strong paternalistic tendency counter to Indian autonomy. In 1913, she attained a longtime goal of establishing a hospital in Walthill, Nebraska, but unfortunately died of cancer in 1915 at the age of 50.

Hospital at Walthill, built by Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte (inset)

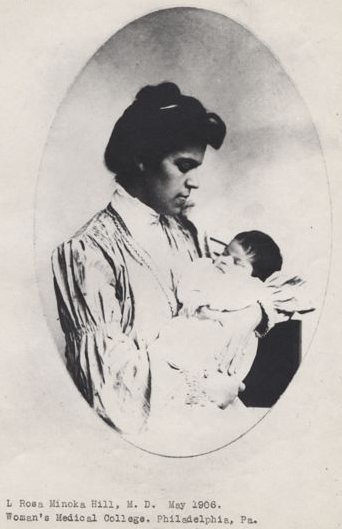

Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill

Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill, Woman's Medical College, May 1906

Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill earned an MD from our school in 1899. She was our second Native American graduate, and sources suggest that she may have been the second Native American woman physician.

Dr. Minoka-Hill’s birth details remain uncertain, but she was probably born in 1875 or 1876 on the Mohawk Indian Akwesasne/Saint Regis Reservation in northern New York and spent her earliest years living with her maternal grandmother in Atlantic City, New Jersey. But at around 5 years old, she was removed from her family to be adopted by a Quaker family in Philadelphia. While Dr. Picotte's family chose to educate her into white cultural norms, Dr. Minoka-Hill's early life and education reflected practice of forced assimilation into white culture.

Minoka-Hill attended the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, where she earned her degree in 1899. After graduating, she worked as an intern at the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia and the Lincoln Institute in Philadelphia, a school for Indian girls. Through a student at Lincoln, she met Oneida Indian Charles Abram Hill, who she married in 1905, and soon after they moved to Oneida, Wisconsin, on his tribal reservation.

Interns at the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia, 1903-04

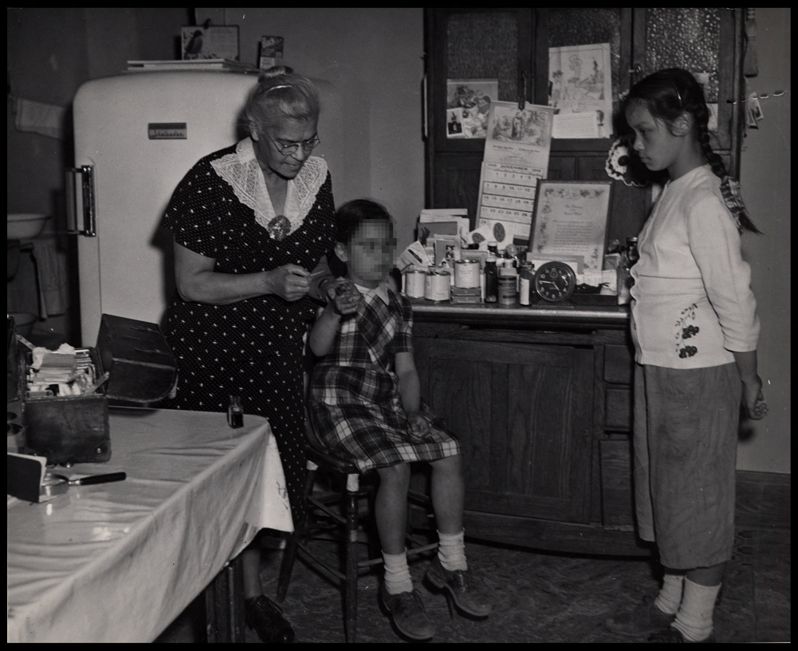

For over 40 years, she provided medical care and public health education on the Oneida Reservation. Despite her childhood, she felt it was her calling to serve the Native American community, and did so, often as the only source of medical care for her community. Starting in the late 1940s, as awareness grew about Minoka-Hill’s long history of humble humanitarian work, she was recognized with a number of awards from medical and Indian organizations, including the American Medical Association and a lifetime honorary membership to the Wisconsin Medical Association.

One honor that was particularly meaningful was her 1947 adoption by the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. They gave her the name Youdagent, meaning “she who carries aid.” At the tribal adoption ceremony, Minoka-Hill said: “It has been a privilege to be helpful to those in need of help and to do it cheerfully and as promptly as I could. Because I felt it was the Master’s work assigned to me I must therefore be a willing worker -- though sometimes a very weary worker. Today you have honored me in a special way by taking me for your ‘almost sister’, now I can say to many of you ‘daughter’, ‘son’, ‘grandchild’.” During the last several years of her life, after suffering several health issues, she had to curtail her house-call practice, instead focusing on her “kitchen clinic” in her home. She died in 1952.

Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka Hill applying first aid for Carol Hause, while her sister Loretta watches intently.

Dr. Minoka-Hill was a Mohawk who grew up in a white Quaker family, became a devout Catholic, practiced medicine for decades among and was adopted by the Wisconsin Oneida, and was a trusted doctor among local non-Indians. She had many influences and influenced many. Minoka-Hill’s granddaughter, poet Roberta Hill Whiteman, wrote an extensively researched 1998 dissertation on Minoka-Hill, imbuing it throughout with personal reflection. Whiteman said “It is impossible to write the story of Dr. Minoka-Hill’s life within the context of her identity as an Indian woman and relinquish an understanding of cultural differences…. She created an identity which valued composites of the communities that affected her.“ (p.16).

How Can Inspiration Help Us Do Better?

Drexel College of Medicine has a 170-year history of providing opportunities for women and underrepresented peoples in the medical profession. This is something that we’ve long been proud of, and we celebrate the fact that some of the earliest Native American doctors graduated from our school. But our track record with AI/AN graduates -- a small handful over 170 years -- points more toward work needed than work done. At our Indigenous Peoples’ Day panel in October 2020, several Native American scholars called us to task to do better. Dr. Rebecca Sockbeson, associate professor with the Department of Educational Policy Studies at University of Alberta, made a strong point about the cascading benefits of establishing strong pipeline programs, which with support of schools, communities, and government, provide on-the-ground mentorship in underserved and underrepresented communities and result in more individuals serving broader communities.

We have a strong pipeline in place with the Drexel Pathway to Medical School program and can use it to build up our student body’s diversity in support of Native American representation. In doing so, we will build on the successes of individuals like Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte and Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill, and celebrate their lives, which they dedicated to providing health care to the underserved and providing inspiration to others within their communities.

For further reading about Drs. Minoka-Hill and Picotte:

The 1998 PhD dissertation by Dr. Minoka-Hill’s granddaughter, poet Roberta Hill Whiteman, is exhaustively researched and includes many personal recollections and reflections on the impact Dr. Minoka-Hill had on individuals and her community: Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill: Mohawk Woman Physician (Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304437247).

A recent biography of Dr. Picotte was published in 2016: A Warrior of the People by Joe Starita, journalist and professor at University of Nebraska - Lincoln - https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1066241151.

Back to Top