Martin Luther King Jr. and Public Health

Posted on

January 27, 2020

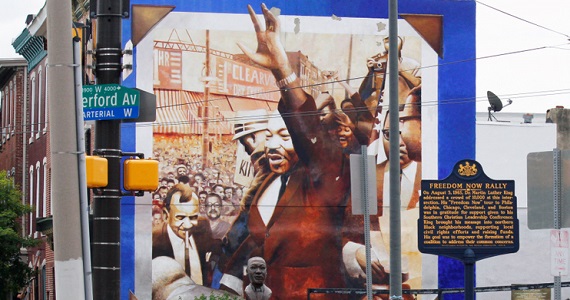

A mural by Cliff Eubanks helps mark the site of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 1965 speech in the Mantua neighborhood of Philadelphia.

A mural by Cliff Eubanks helps mark the site of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 1965 speech in the Mantua neighborhood of Philadelphia.

By Ana V. Diez Roux, MD, PhD, MPH

On March 25, 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the annual meeting of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Chicago. According to an Associated Press (AP) story published by the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern on March 26, King and officers of the Medical Committee for Human Rights called for doctors and hospitals to comply with the Civil Rights Act and accused the American Medical Association of a “conspiracy of inaction” in civil rights. It was there, at a press conference before the meeting, that King uttered a phrase that is often quoted in public health, a phrase alluding to injustice in heath as “the most shocking and the most inhuman” of all forms of inequality.

There appears to be no formal record of exactly what he said, only what was captured in news stories of the time. The AP story quoted King (who was referring to the pervasive discrimination experienced by both Black patients and Black doctors in hospitals across the United States) as saying: “We are concerned about the constant use of federal funds to support this most notorious expression of segregation. Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death. I see no alternative to direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.”

A subsequent story in Cleveland’s Call and Post on April 16, 1966, has a slightly different version of the famous quote: “Of all forms of discrimination and inequalities, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” In other places King’s words are quoted in yet a third form: “Of all forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

Regardless of the specific words King used, which we may never know for sure, a critical element is King’s embedding of these words in an explicit call to action, a “direct action” campaign that included legal recourse to force hospitals to end discrimination. King and the Medical Committee for Human Rights emphasized that this discrimination was not only a problem in the South but was also pervasive in hospitals in the north, including Chicago. King buttressed his call to action by noting that the Black infant mortality rate in Chicago’s Woodlawn area was as bad as the rate in Mississippi.

We have all seen versions of King’s famous words flashed across screens in countless PowerPoint presentations. And they are indeed inspiring, especially when placed in their historical context, in the context of the social movement to end segregation and discrimination, in the context of the struggle for civil rights and social justice that King was such an important part of in the United States.

But of course, King’s speeches and writings (many relevant to public health) are much broader than this phrase. Recently, after hearing a passing reference to it on the radio, I looked up King’s “Keep Moving from This Mountain” address that he delivered at Spelman College in 1960, six years before the Chicago event. In this address, King famously refers to the four symbolic mountains that we must overcome “if we are to go forward in our world and if civilization is to survive.” I was struck by how relevant his words are today, nearly 60 years later.

The first mountain King refers to is the mountain of moral and ethical relativism. King says, “To dwell in this mountain has become something of a fad these days, so we have come to believe that morality is a matter of group consensus.” He alludes to the fundamental role of education in overcoming this mountain. Education, King argues, “must help an individual think intensively, critically, imaginatively.” However, it must also transmit and promote a sense of moral and ethical values. As King put it, “The proper education will not only give the individual the power of concentration but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate.”

King’s second mountain is the mountain of practical materialism. By practical materialism he means “living as if there were nothing else that had reality but fame and material objects.” He calls for a more humane and just economic order, and an end to exploitation and global inequality.

The third mountain is the mountain of racial segregation. King sees the fight against racial segregation as part of the struggle for equality worldwide, “And so, today, let men everywhere join in this quest for freedom by moving out of the mountain of racial segregation.”

Last but not least, King discusses hatred and violence as the fourth mountain. “[A]t one point in my intellectual pilgrimage I justified war, certainly as a sort of negative good in the sense that it blocked an evil force, a totalitarian force. I have come to believe firmly now that war can no longer serve even as a negative good…There was a time when we had a choice of violence or nonviolence, but today it is either nonviolence or nonexistence.” It is in discussing the fourth mountain that he outlines the principle of nonviolent resistance that underpinned the movement he led.

In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times, Charles Blow wrote “As I child, I idolized the narrowed King. As an adult I love the more complicated King: agitated, exhausted and even angry.” He talks about how King’s thinking evolved over time, as all of our thinking does as we try to understand the world and figure out how to make it better. Blow refers to subsequent speeches by King where he discusses tempering his earlier optimism with realism, where he discusses entrenched racism, where he speaks against the Vietnam War, and the economic structures that reinforce racism and inequality, and calls for a different economic order.

Not all will agree with every component of King’s argument and vision; we may debate the causes and the best actions. But it is so enriching and inspiring to go back and read the words as he said them, in all their power, eloquence, and beauty.

As I read the “Keep Moving from This Mountain” address, I found myself wishing I had been there among the Spelman students that day, listening as King spoke. New mountains have emerged, perhaps, but the four mountains King alluded to are undoubtedly still with us today, here in the United States but also worldwide.

This month I hope you take a moment to read this address or other King speeches and rediscover the power of words (and ideas) to challenge, guide, and inspire us as a University, as a School of Public Health, and as citizens of this world.